Plastic Politics¶

Revisiting Politicisation and Depoliticisation in Post-War Dutch History¶

Ruben Ros

Series Digital History¶

This article is part of a series on digital history in the Netherlands and Belgium. Twelve years after the publication of the widely-read BMGN-issue on digital history in 2013 (https://bmgn-lchr.nl/issue/view/31), this series aims to provide a new state of the field. It comprises four serially published articles, which collectively emphasise the diversity of researchers, questions, methods and techniques that define digital history in 2025. The articles are published online in a new, HTML-based format that better showcases the methods and visualisations of the research published here.

Serie digitale geschiedenis¶

Dit artikel is onderdeel van een serie over digitale geschiedenis in Nederland en België. Twaalf jaar na het veelgelezen BMGN-nummer over digitale geschiedenis uit 2013 (https://bmgn-lchr.nl/issue/view/31) maken we een nieuwe tussenstand op. De serie bestaat uit vier serieel gepubliceerde artikelen, die tezamen de veelzijdigheid accentueren van de onderzoekers, de vragen, de methoden en technieken die anno 2025 digitale geschiedenis definiëren. Deze artikelen worden online in een nieuw, op HTML gebaseerd format gepubliceerd, waardoor de methodologische toelichting en visualisaties van het hier gepubliceerde onderzoek beter tot hun recht komen.

Introduction[1]¶

‘Development, precision, justice. Who could oppose these values? They can encompass almost anything, which makes them especially useful in a philosophy of depoliticisation’.[2] Former Dutch Prime Minister Joop den Uyl struggled to conceal his frustration. He accused the new Van Agt government of lacking a clear mandate and undermining democracy by avoiding concrete policy commitments. One month earlier, in December 1977, an attempt to continue his progressive government had failed. Despite another victory by Den Uyl’s Labour Party (PvdA) and six months of negotiations with Social Liberals (D66) and Christian Democrats (CDA), the latter suddenly allied with the Liberals (VVD), forming a new government and installing Dries van Agt as Prime Minister. In January 1978, Den Uyl found himself as leader of the opposition in the House of Representatives. His agenda of redistributing ‘income, knowledge and power’ was abandoned for the idea that ‘government is not capable of remedying all the shortcomings in society and meeting all its needs’.[3] In the eyes of Den Uyl, this meant not only a departure from progressive political goals, but also from open political debate. He argued that the new government’s plans manifested an ‘evasion of choice and the covering up of real contradictions’.[4] Instead of pursuing structural change and political choice, he argued, the Van Agt government spread a ‘grey cloak’ of depoliticisation over the country (Illustration 1).[5]

In retrospect, Den Uyl’s critique of depoliticisation foreshadows current scholarship in politicisation and depoliticisation. Since the 1990s, political scientists have used these concepts for understanding democratic decision-making. Central to this work is the idea of (de)politicisation as ‘agenda-shifting’. According to the political scientist Colin Hay, issues become political if they move from ‘non-political’ spheres such as science or the private sphere to the sphere of choice and decision-making.[6] Conversely, if an issue is depoliticised, it moves from the sphere of politics to a non-political sphere. Here, an issue is no longer debatable and open for conflict and choice, but considered necessary, unavoidable and closed. This can be done by putting decision-making power in the hands of non-political institutions (such as the World Trade Organization), by establishing rules that bind the political capacity for choice and deliberation (such as the budgetary rules in the European Stability and Growth Pact), or by simply presenting an issue as a matter of scientific truth, common sense or otherwise non-political in discourse.[7] According to Den Uyl, the Van Agt cabinet was complicit in this kind of depoliticising discourse.

The concepts of politicisation and depoliticisation resonate strongly in scholarship on post-war Dutch history. In fact, historians tend to consider the second half of the twentieth century a pendulum that swings between periods of politicisation and depoliticisation. This account of post-war politics typically starts with depoliticised pacification in the 1950s. In 1968, the political scientist Arend Lijphart coined the concept of pacification democracy to explain the remarkable stability of the Dutch political system between 1917 and 1967. He argued that elites managed socio-political diversity by persistently depoliticising potential sources of discord, resolving them behind closed doors and presenting them as ‘issues that could be addressed according to objective, established principles of economic theory, arithmetic (proportionality) or jurisprudence’.[8] In the late 1960s, however, Dutch elites increasingly struggled to keep discord at bay. Progressive movements and parties successfully promoted issues of democratic participation, environmental protection and gender equality to the space of public deliberation and ideological conflict.[9] As Hans Daalder observed in 1974, pacification had made way for politicisation and polarisation.[10] Similar to other Western European democracies, a politicised era succeeded years of depoliticised democracy.[11] Soon, as Den Uyl’s remarks indicate, depoliticisation returned. In 1982, after an earlier conservative pivot in 1978 and failed attempts to reboot collaboration between PvdA and CDA, a new coalition of Christian Democrats and Liberals took over.[12] Led by the Christian Democrat Ruud Lubbers, it took a decisive turn towards austerity, privatisation, deregulation and decentralisation. Comprised of former business leaders and managers, the Lubbers government styled itself as taking a so-called no-nonsense approach, presenting policies as necessary for saving the Dutch economy.[13] With this ‘new business-like politics’, it seemed as if ‘the pacification of the 1950s had returned’, as the historian Herman De Liagre Böhl argues.[14] After a brief interlude of politicisation, Dutch politics nestled beneath the grey cloak of depoliticisation.[15]

The idea of alternating periods of politicisation and depoliticisation can be found in textbooks and studies into the long-term development of Dutch society and politics.[16] At the same time, the pendular account and the idea of (de)politicisation as agenda-shifting have faced criticism. With the cultural and linguistic turns in late twentieth-century political history, historians have largely abandoned the study of politics as a fixed institutional space that comprises parties, politicians and parliaments.[17] They increasingly observe the political through the lens of previously overlooked practices, actors and stages, such as petitioning, protest movements and public meetings.[18] Since the ‘new political history’ of the 1960s, the political history from below-approach seems to continuously extend the field of political history. In conjunction with this focal shift towards alternative actors, political historians also understand politics as contingent: defined, construed and performed differently over time. Therefore, political historians have taken a greater interest in the symbolic, performative and discursive aspects of the political.[19] For the study of (de)politicisation, this dual shift has significant consequences. Scholars study politicisation beyond the level of formal political actors and problematise the distinction between political and non-political spheres. Accordingly, recent work on the topic tends to focus on the discursive construction of issues as political and non-political.[20]

These changing questions and methods coincide with critique and revisionism regarding the pendular image of post-war Dutch political history. Since at least the 1980s, historians have implicitly or explicitly challenged the idea of alternating periods of politicisation and depoliticisation. Lijphart’s ‘pacification democracy’ has been criticised as a caricature that obscures forms of political conflict in the mid-twentieth century.[21] Similarly, contrasts between the ‘pragmatic’ 1950s and ‘political’ 1960s have been the object of revisionism since at least the 1990s.[22] Recently, scholars of neoliberalism have pointed to fierce ideological confrontations over economic policy in the 1950s and 1980s – decades traditionally seen as relatively depoliticised.[23]

The broader cultural or discursive perspective on (de)politicisation also serves to problematise the latent normativity in the pendular account of post-war Dutch history. Historians long presented the progressive decade as a transgression of a culture typically characterised by negotiation, consensus and harmony.[24] Challenging these self-congratulatory depictions of Dutch harmony, historians have highlighted the frequent upheavals, conflicts and resentments in modern Dutch history.[25] By looking beyond formal institutional spaces, they observe how mass media, popular culture and protests have shaped and expanded the political over time.[26] Politics, it appears, is everywhere in Dutch history. Taking a broader view at the political thus complicates the image of (de)politicisation as the transfer of issues to supposedly political and non-political spheres. As such, it also invalidates models of Dutch political history as characterised by perpetual harmony or pendular movements between politicisation and depoliticisation.

However, such a wider view also comes with its own limitations. Due to the complexity of dissecting discourse, cultural and discursive approaches to political history tend to focus on concrete events, persons and transitions rather than long-term cultural developments. Political historians, in their efforts to understand how politics was defined and performed across diverse historical and actorial contexts, meticulously reconstruct historical discourses.[27] As early critics of the cultural turn have argued, this comes at the expense of ‘explanatory ambition’.[28] The cultural and discursive approach to the political is seen as favouring the ‘depth of reading above breadth of causal explanation’.[29] While such an approach is essential to understand and contextualise idiosyncratic conceptions and articulations of politics in the past, it seems less well equipped to grasp (de)politicisation as a process – one that unfolds, accelerates or slows over time.[30]

In this article, I argue that we can combine the discursive approach and constructivist sensitivity to (de)politicisation with a more systematic and process-oriented approach. I do so by analysing what I call ‘conducive abstraction’ and ‘plastification’ as expressions of, respectively, conceptual politicisation and depoliticisation. Conducive abstraction refers to the process by which a concept becomes open to conflicting political meanings. Plastification refers to the expression of an abstract word as if it concerns a concrete thing that allows no interpretation but necessitates certain actions. I study these processes on the level of words contained in the speeches of politicians as members of the Dutch House of Representatives. I use all parliamentary speeches from the period between 1945 and 1994. This includes speeches delivered in plenary debates and committee meetings. It excludes those delivered in committee meetings that were not public.[31]

By studying conducive abstraction and plastification in parliamentary language, I hope to provide new insights into the long(er)-term development of politicisation and depoliticisation as dynamic processes in the history of Dutch democracy. Investigating (de)politicisation at scale is important, as political analysts diagnose current democracies either overly politicised or increasingly devoid of politics due to the rise of technocratic governance.[32] Ideas about past moments and forms of (de)politicisation structure debates about current democratic challenges.[33] Hence, a systematic understanding of historical (de)politicisation is crucial for understanding and improving democracy today.

This article aims to contribute to this ambition by studying particular forms of (de)politicisation in the context of Dutch parliamentary debate between 1945 and 1994. After a brief excursus into my approach, I analyse the words that are detected as undergoing conducive abstraction, as well as the diachronic development of the intensity of abstraction. The last three paragraphs of the article take a similar approach to conceptual depoliticisation by looking at concepts that ‘plastify’ in parliamentary language use. By looking at ‘plastic words’ and the diachronic rate of plastification, I provide an alternative account of the character and periodical appearance of depoliticisation.

Approach and method¶

This article combines a discursive approach to (de)politicisation with a systematic long-term perspective. Because manifold forms and dimensions of conceptual (de)politicisation exist, I choose to focus on two specific processes: ‘conducive abstraction’ and ‘plastification’. I take them as expressions of, respectively, conceptual politicisation and depoliticisation. Inspired by the work of the German historian Reinhard Koselleck, I coin the term conducive abstraction to refer to the process in which a concept is imbued with political meanings and associations, and when it is used in an ideological framework that sketches a problematic past and a desirable future. As such, conducive abstraction is a process akin to what Koselleck has called the ‘temporalisation’ and ‘ideologisation’ of concepts. In his work on conceptual change between 1750 and 1850, Koselleck argues that concepts became political in the sense that they operated as bridges between the ‘space of experience’ and the ‘horizon of expectation’ – spaces that were increasingly diverging in this period.[34] Political concepts describe the past and prescribe a future. I use the concept of conducive abstraction to refer to this process of conceptual politicisation by means of temporalisation and ideologisation.

Conversely, I study conceptual depoliticisation through the lens of plastification. The German linguist Uwe Pörksen coined the term ‘plastic words’ to refer to abstract concepts that are used as if they refer to concrete things. Words such as ‘information’ (‘informatie’), ‘management’ (‘management’), ‘system’ (‘systeem’) and ‘project' ('project’), used abundantly by experts, generate ‘needs and uniformity’. As such, they are depoliticising, as Pörksen argues. They give the appearance that an objective, tangible reality necessitates a certain course of action, which leaves little room for choice and deliberation.[35]

I argue that the processes of conducive abstraction and plastification can be detected at the level of individual words present in parliamentary speeches. In the online to this article, I explain how we can combine information on how frequently a word is used in Dutch parliament over time and how abstract that word appears in language to measure conducive abstraction and plastification. I measure the ‘abstractness’ of a word with so-called word embedding models. These models have become popular tools for studying the meaning of a word over time.[36] They allow, for example, the detection of what I call semantic neighbours that indicate the changing meaning of a word. If we train one model on parliamentary debates from the 1950s, and another on debates from the 1980s, the model would find that the word ‘armoede’ (‘poverty’) is surrounded by neighbours such as ‘hunger’ (‘honger’), ‘misery’ (‘ellende’) and ‘suffering’ (‘lijden’) in the former period and ‘insecurity’ (‘onveiligheid’), ‘unemployment’ (‘werkloosheid’) and ‘vandalism’ (‘vandalisme’) in the latter. These changing neighbourhoods illustrate a shift in the meaning and use of a concept.

Beyond exploring neighbourhoods – a method nonetheless applied in this article as a means to contextualise semantic change – word embedding models also capture specific semantic features of words. For example, researchers showed that models reflect gender bias by pointing out that words such as ‘doctor’ and ‘nurse’ cluster closer to, respectively, male- and female-associated terms.[37] Similarly to this ‘maleness’ or ‘femaleness’, the abstractness of a word can be estimated using word embedding models. I use seed lists of highly abstract and highly concrete words as semantic poles or axes, and then calculate the abstractness of other terms in the model in relation to those poles. The word ‘cow’, for example, is closer to the concrete seed lists that comprises ‘glass’, ‘water’ and ‘tree’ than it is to the abstract seed lists that contain ‘freedom’, ‘ideal’ and ‘future’. Conversely, the word ‘democracy’ is closer to the latter seed list of abstract terms. Because I train word embedding models on parliamentary speeches from different (six-year) periods, I can extract an abstractness signal for thousands of words used in the proceedings. Combining these signals with information on diachronic frequency then allows me to model conducive abstraction as the parallel increase in abstractness and frequency, and plastification as the parallel decrease in abstractness and increase in frequency. In the following sections, I show what such an analysis tells us about (de)politicisation in post-war Dutch political history.

Conducive abstraction¶

‘What used to be considered “voice” [inspraak] in the past was voice without speaking: the voice of the heart, of consciousness, of nature, of love, of hate (…).The new concept of voice has not yet been defined in the dictionary’.[38] Henk Beernink, the Orthodox Protestant (CHU) Minister for the Interior, was keenly aware of the new concepts that had entered parliamentary language in the late 1960s. Frustrated by a lack of democratic participation, progressive movements such as the New Left and new parties such as D66 had confronted the establishment with demands for transparency and participation. In factories, universities and bureaucracies, people should have a voice, they argued.[39]

The example of ‘voice’ illustrates an important feature of conceptual politicisation. As the cognitive scientists Claudia Mazzuca and Matteo Santarelli argue, ‘the process through which politicization is made possible necessarily entails making the concept partially indeterminate, open to revisions and further determination, hence highlighting its more “abstract” components’.[40] As Beernink explained, voice no longer pertained to the many ways in which one could experience the voice of the heart, nature or love. Instead, progressives employed a more general, singular and abstract sense of the concept that applied to civic participation in democracy. In this section, I use this link between abstraction and politicisation to study conducive abstraction. The politicisation of a concept entails its inclusion in a regime of temporality, which runs parallel to a growing potential for ideological use.[41] The concept of voice, as used by progressives, was part of a narrative or argument that diagnosed a lack of participation in the present and emphasised the need for democratic reform in the (near) future. This ideological temporality formed the bedrock for political conflict, as political actors disagreed with the diagnosis of lacking voice or imagined alternative ways of reforming democracy. The movement from neutral concreteness to ideological abstractness is therefore conducive: it provides the basic condition for politicisation.

As explained in the , I model conducive abstraction as the combined increase in lexical frequency and abstractness. If a concept is used in a more political sense, I expect this to be reflected in its increasing popularity and increasing abstractness. Although this operationalisation of conducive abstraction is coarse and does not preclude the possibility of other forms of conceptual politicisation existing in parliament, I will demonstrate that it successfully captures one specific process of politicisation. In the following two sections, I first discuss the concepts that are identified as subject to conducive abstraction. Next, I examine what they tell us about the process of politicisation as it appears, accelerates and falters in the House of Representatives.

Political abstractions¶

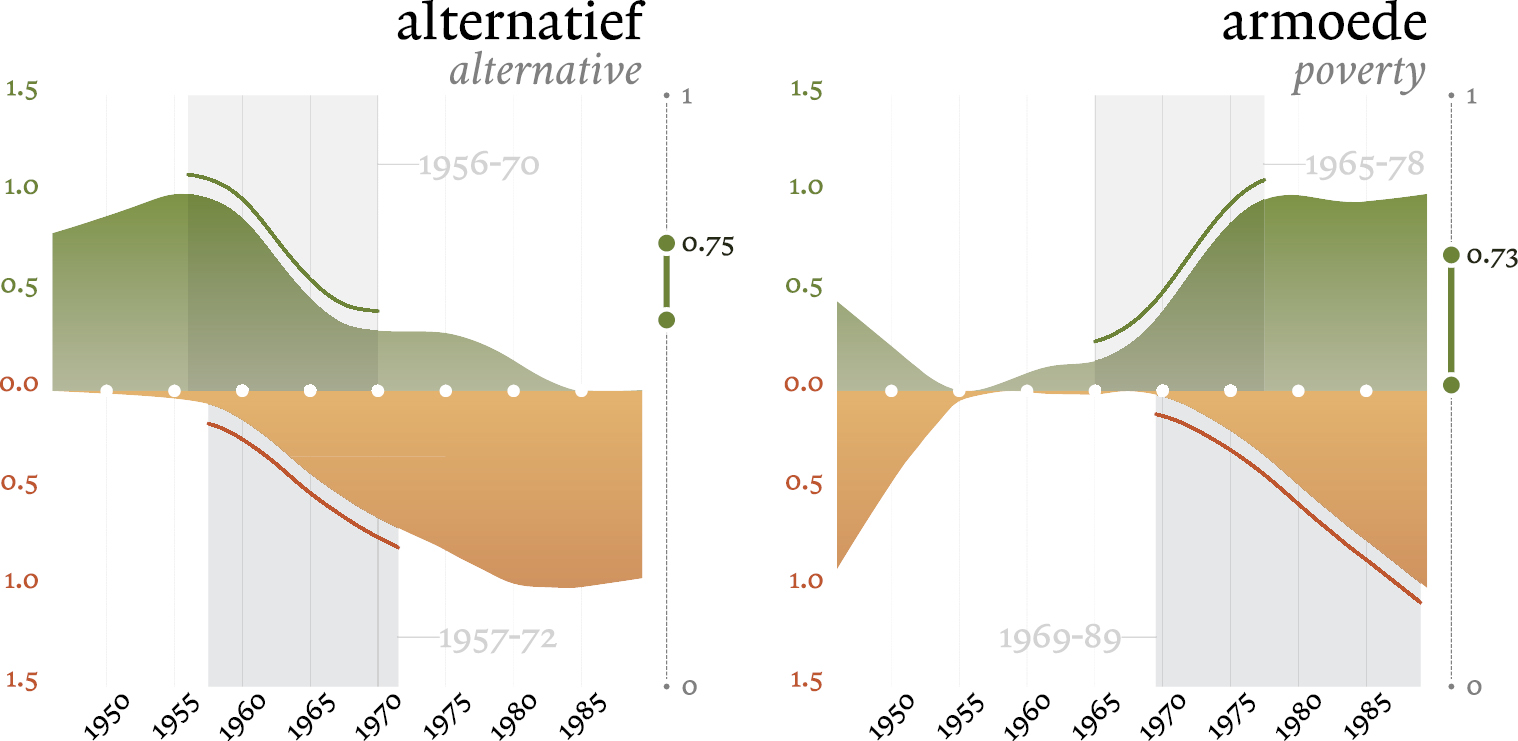

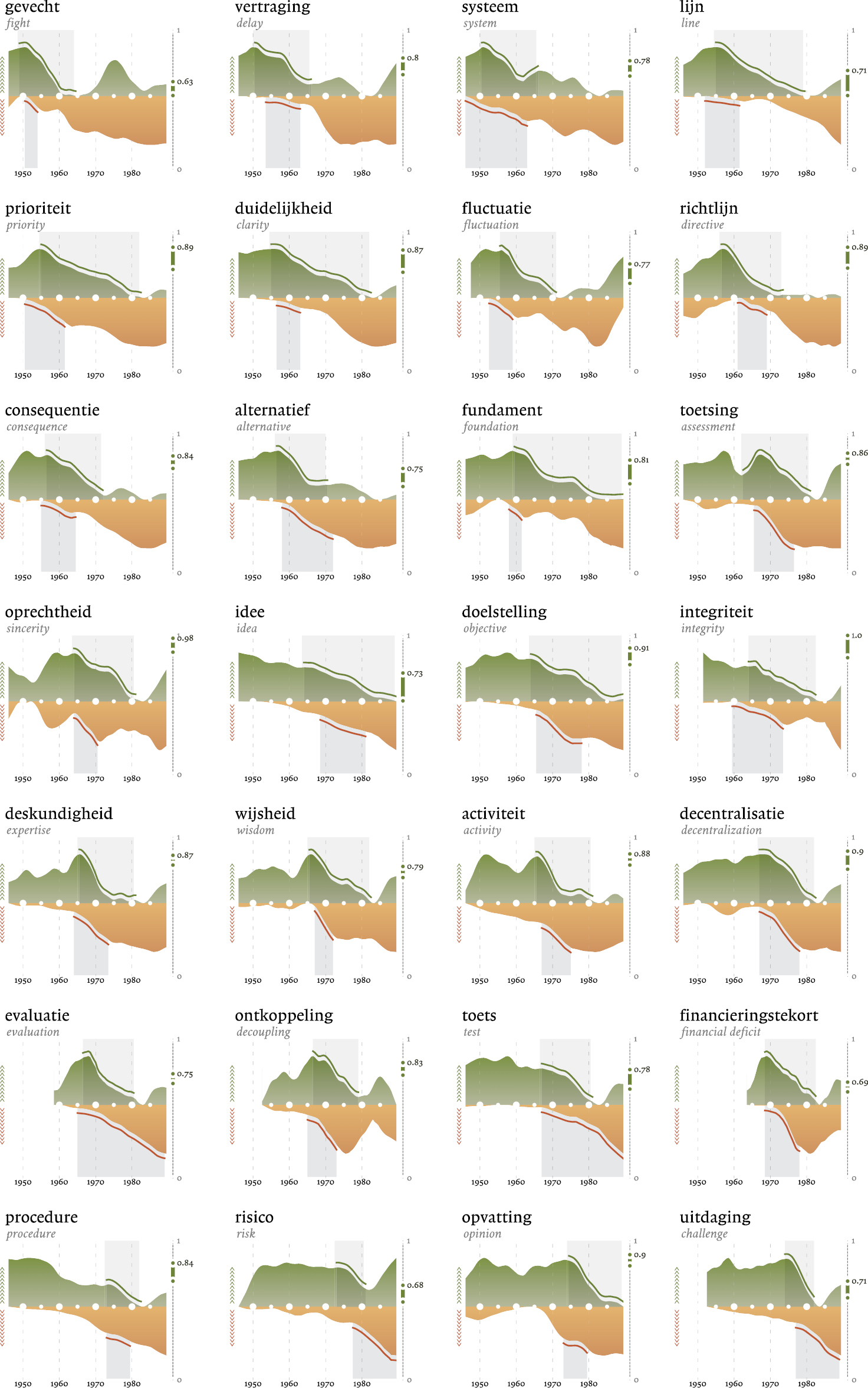

Using the model of conducive abstraction as a filter, I sift through thousands of words used in parliament between 1945 and 1994, allowing only those terms that show growth in both frequency and abstractness to pass through. This leads to a selection of about 1,100 concepts (for a random selection of 28 out of the 1100 filtered words, see Figure 2). In this section, I discuss three semantic categories (issues, actors and values) that emerge from a manual categorisation of the detected concepts. These categories provide a first grasp of conducive abstraction as a process in the House of Representatives.

Covering concepts such as ‘budget shortage’ (‘begrotingstekort’), ‘unemployment’, ‘pregnancy’ (‘zwangerschap’), ‘poverty’ and ‘environment’ (‘milieu’), the first category conforms to the traditional understanding of politicisation as an ‘issue becoming subject to public deliberation, decision making and contingency where previously it was not’.[42] This shows in the concept of ‘environment’. Previously referring to various (concrete) physical environments, the concept became associated with ‘nature’ (‘natuur’) and ‘landscape’ (‘landschap’), and values such as ‘livability’ (‘leefbaarheid’) and ‘beauty’ (‘schoonheid’), from the 1960s onwards. By 1970, the collective singular ‘the environment’ (‘het milieu’) operates as a locus of conflicting and competing political viewpoints. Detected terms also highlight lesser-known concepts such as ‘fluorisation’ (‘fluoridering’). Adding fluoride to drinking water had become popular in the 1960s as a way of improving dental health. In the late 1960s, side effects sparked societal unrest, and the issue became fiercely contested. Conservative politicians (mostly members of the VVD and SGP) saw the issue as symptomatic of new forms of state intervention in the private sphere.[43] The appearance of semantic neighbours such as ‘abortion’ (‘abortus’), ‘air pollution’ (‘luchtvervuiling’) and ‘vaccination’ (‘vaccinatie’) points to the attempts of these politicians to connect fluorisation to other political issues. As such, the conducive abstraction of the concept points to the new ideological conflict over the issue.

The second category of concepts shows how conducive abstraction applies to more than just issues. Examples such as ‘policeman’ (‘politieman’), ‘caravan dwellers’ (‘woonwagenbewoners’), ‘minority’ (‘minderheid’), ‘resident’ (‘inwoner’) and ‘low income earners’ (‘minima’) point to actors and identities that were becoming increasingly contested. Until 1960, ‘motorist’ (‘automobilist’) was a scarcely used, neutral descriptor. After this year, it comes to signify a fiscal and economic category, as associated terms such as ‘car owner’ (‘autobezitter’), ‘taxable’ (‘belastbaar’) and ‘citizen’ (‘burger’) show. This, in turn, sets the stage for contestation over the now taxable motorist, with the liberal VVD seizing the moment to become the party that represents the interests of car owners.[44] Similarly, the concept of ‘minority’ was used to refer to parliamentary minorities until the 1950s. In the 1960s, when anti-colonial struggles and racial conflict in South Africa led Dutch politicians to talk about ‘white minorities’ (‘blanke minderheden’), the concept became associated with race and culture.[45] In the early 1970s, this cultural conception was applied to Dutch ‘minorities’, when for instance the Moluccans were categorised as such, and corresponding debates over assimilation and discrimination took place in parliament (Illustration 2).[46] Although there appears to be no strict division between issues and actors, the conducive abstraction of terms referring to the latter category shows that politicisation is not just the transfer of pre-existing issues to the realm of politics. The process of politicisation also comprises the construction of new identities and actors as political objects.

The last category observed in the data consists of words that indicate values. Examples are ‘privacy’ (‘privacy’), ‘transparency’ (‘openbaarheid’), ‘livability’ (‘leefbaarheid’), ‘freedom of choice’ (‘keuzevrijheid’) and ‘equality’ (‘gelijkheid’). The last concept becomes more abstract from the late 1960s onwards, as it transforms from a legal criterion to a central value of progressive politics in the 1970s. Seemingly more neutral values, such as ‘feasibility’ (‘uitvoerbaarheid’), ‘efficiency’ (‘efficiëntie’) and ‘effectiveness’ (‘effectiviteit’) are similarly marked by conducive abstraction. ‘Feasibility’, for example, moves from being a technical qualifier to a more normatively imbued demand. In the 1950s, members of parliament and the government talked about ‘practical’ or ‘technical’ feasibility.[47] Increasingly from the late 1960s onwards, the concept was used without adjectives and became enmeshed in broader concerns about administrative and financial efficacy.[48] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the concept was used by fiscal conservatives to attack the ambitions of the earlier Den Uyl cabinet. Illustrating the inclusion of the concept in a new prescriptive temporality, the leader of D66 Laurens-Jan Brinkhorst argued that ‘Legislation has become far too complex and has barely been tested for feasibility. Insufficient oversight has led to an unchecked proliferation of subsidies and subsidised institutions’.[49]

In sum, the model of conducive abstraction effectively identifies concepts that are increasingly used in a more general, abstract and political way. This approach not only captures shifts in political agendas but also reveals how identities and values become sites of contention. By detecting patterns of increasing frequency and abstraction, the model offers a broader perspective on politicisation — extending beyond the traditional focus on agenda-setting to encompass the ideological framing of issues, actors and values.

Processes and periods of politicisation¶

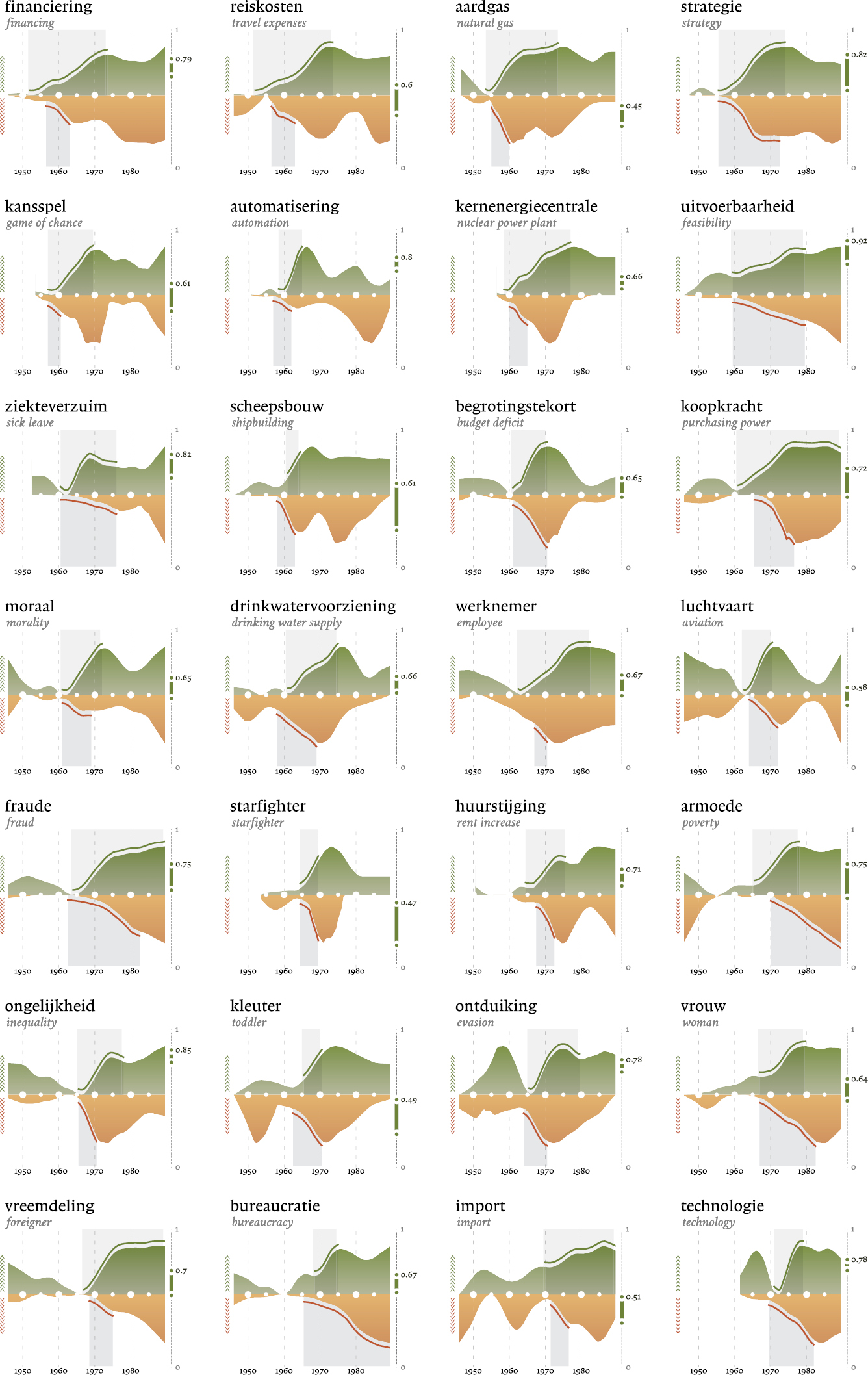

Studying politicisation through the lens of concepts allows us not only to trace individual instances of conceptual politicisation, but also to understand it as a dynamic process. Because I study conducive abstraction at the level of ‘word periods’ (specific segments in a time series of a term’s frequency and abstractness), I can aggregate time series to reveal larger trends. These trends allow us to understand politicisation as a process that accelerates or slows over time. In this section, I calculate the aggregate density of conducive abstraction as the main aggregated trend (Figure 3). In the density signal, I observe two moments of heightened conducive abstraction. Understanding these moments, I argue, enriches traditional accounts of post-war politicisation in Dutch political culture.

From protest to policy¶

The trend in Figure 3 shows a first period of increased conducive abstraction between roughly 1958 and 1973 – the period that is sometimes referred to as the long 1960s.[50] This period covers about half of the terms that show conducive abstraction in the post-war period. They seem to confirm the reputation of the long 1960s as a period of politicisation in areas of environmentalism, feminism and democratic renewal. The conducive abstraction of ‘discontent’ (‘onbehagen’), ‘unrest’ (‘onrust’), ‘constitutional reform’ (‘grondwetswijziging’) and ‘protest’ (‘protest’) exemplifies the progressive thrust behind politicisation in the period. However, looking more closely at the terms that grow more abstract and their trajectories of conducive abstraction complicates a mere validation of established ideas about politicisation.

First, most terms that become more abstract in this first period do not signify the issues, actors and values traditionally associated with progressive politicisation. As found already in the previous section, conducive abstraction decentres the thematic focus of common understandings of politicising periods: ‘Equality’ becomes more abstract, but so do ‘motorist’ and ‘efficiency’. In fact, another thematic centre appears from the terms that grow more abstract between 1958 and 1973. Most of them seem to relate to budgets, economic challenges and financial constraints, as examples such as ‘financing’ (‘financiering’), ‘income’ (‘inkomen’), ‘budget shortage’, ‘cost factor’ (‘kostenfactor’) and ‘feasibility’ indicate. I take them to be reflections of the gradual but persistent politicisation of economic policy. As recent work on the Dutch history of neoliberalism emphasises, the abandonment of the guided wage policy and the increases in state spending prompted concern and criticism among fiscal conservatives and early adopters of ‘new public management’, a governance approach that applied management principles of the private sector to the public sector, emphasizing efficiency, competition, performance measurement, and cost-cutting to reduce government inefficiencies and control spending. Fearing interest groups and inflationary spirals, politicians such as Willem Drees Jr., leader of the Social Democratic offshoot party DS’70, argued for stronger financial constraints and strict budgetary limits.[51] It appears that this gradual politicisation of economic and budgetary concerns comprises a substantial proportion of the terms subject to conducive abstraction in this period.

The second way in which the trend in Figure 3 problematises a validation of progressive politicisation is the surprisingly early end of conducive abstraction in the early 1970s. The period in which Den Uyl was Prime Minister (1973-1977) does not appear as the peak of politicising zeal, but rather as the onset of its recession. This is visible in the declining abstractness of, for example, ‘society’ (‘samenleving’), ‘prison sentence’ (‘gevangenisstraf’), ‘union’ (‘vakbond’), ‘human right’ (‘mensenrecht’), ‘labour time’ (‘arbeidsduur’) and ‘minority’. After having been more abstract in the long 1960s, these terms became more concrete in the mid-1970s. Meanwhile, their frequency does not seem to decline. I interpret this persistent salience and decreasing abstractness as a sign of ‘governmental politicisation’. In response to the call for discursive approaches, Colin Hay argues that they are not opposites to institutional or governmental politicisation, but often precede it.[52] Legislation and policymaking follow the presentation and narration of a concept as political. It seems that concretisation in the mid-1970s signals this chronology. In 1970, ‘environment’, for example, is surrounded by terms such as ‘living climate’ (‘leefklimaat’), ‘atmosphere’ (‘atmosfeer’), ‘status’ (‘status’), ‘life’ (‘leven’) and ‘society’ (‘samenleving’). By 1978, distinctive neighbours are ‘landscape protection’ (‘landschapsbescherming’), ‘wildlife’ (‘fauna’), ‘ecosystem’ (‘ecosysteem’), ‘environmental protection’ (‘milieubescherming’) and ‘environmental management’ (‘landschapsbeheer’). Similarly, ‘voice’ (‘inspraak’) had left the phase of semantic change by the mid-1970s. Whereas its neighbours included ‘communication’ (‘communicatie’), ‘citizenry’ (‘burgerij’), ‘decisional power’ (‘beslissingsmacht’), ‘creativity’ (‘creativiteit’) and ‘freedom’ (‘vrijheid’) in 1970, these words were exchanged for ‘participation procedure’ (‘inspraakprocedure’), ‘participative possibility’ (‘inspraakmogelijkheid’), ‘policy preparation’ (‘beleidsvoorbereiding’), ‘stakeholdership’ (‘zeggenschap’) and ‘advisement’ (‘advisering’) in 1978.

This apparent institutional politicisation challenges the binary opposition between the politically charged 1960s and 1970s and the supposedly less political or more ‘pragmatic’ 1980s. Besides its different thematic focus, the red of protest signs and manifestos slowly faded to the grey of policy documents and bills. Or, as one VVD politician remarked in 1979: ‘The students of the 1960s are the note-takers and innovators of the 1970s’.[53]

Neoliberal politicisation¶

Validating existing scholarship, the model highlights the 1960s and 1970s as a moment of relatively intense conceptual politicisation. It also, however, nuances the temporal scope and thematic focus of politicisation in this period. As can be seen in Figure 3, a second surprising feature of the density trend is the increase in density in the 1980s, a period associated with depoliticisation rather than politicisation. What drives this moment becomes clear from two categories of terms.

First, the 1980s witness a surge in the abstraction of issues, actors and values related to economic policymaking. Examples are ‘efficiency’, ‘complexity’ (‘complexiteit’), ‘remediation’ (‘heronderhandeling’), ‘redistribution’ (‘herverdeling’), ‘tax reform’ (‘belastinghervorming’), ‘balance’ (‘balans’) and ‘financing’. The identification of these terms as subject to conducive abstraction is surprising, given the reputation of the 1980s as an era of depoliticisation, especially in the realm of economic policymaking.[54] Patterns of conducive abstraction show that, at the level of concepts, politicisation was in full swing. ‘Complexity’, for example, is used as an attribute of various issues and problems until the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, by contrast, it is placed in an ideological narrative that emphasises a government that, in the 1970s, overstepped and overburdened society and the taxpayer with a complex jungle of red tape and unfeasible ambitions.[55] The abstractions of austerity thus came with an ideological temporality that emphasised the sins of the 1970s and the necessity to fiscally atone for them in the 1980s. While the intent of such language might be depoliticising, the model of conducive abstraction unveils this neoliberal discourse as deeply political. Moreover, the identified terms reveal continuities. The gradual politicisation of economic and budgetary concepts that started in the long 1960s seemingly reaches its peak in the early 1980s. Terms such as ‘financing’ and ‘feasibility’ – increasingly taken up in ideological frameworks from the 1960s onwards – came to the surface as hallmarks of a new neoliberal ideology. Instead of a sudden switch to a depoliticised neoliberal consensus, conducive abstraction thus points to the 1980s as a moment of politicisation that had been long in the making.[56]

In addition to the language of economic policy, conducive abstraction applies to a second category of terms. ‘Morality’ (‘moraal'), ‘rule of law’ (‘rechtsstaat’), ‘humanity’ (‘menselijkheid’), ‘tolerance’ (‘tolerantie’), ‘integration’ (‘integratie’), ‘society’ and ‘equality’ show that the process goes beyond economic language. I take these terms as a confirmation of what historian Merijn Oudenampsen identifies as a moralistic and communitarian variant of neoliberalism in the Netherlands.[57] Whereas neoliberal ideology in the Anglo-Saxon context was often connected to individualism, Dutch Christian Democrats wedded their faith in the market to a focus on families, communities and ‘responsibility’ (‘verantwoordelijkheid’). In parliamentary language, this seems reflected in a wave of conducive abstraction. The concept of ‘morality’ is a case in point. Until the late 1970s, morality described a domain of ethical principles, as neighbours such as ‘religion’ (‘religie’) and ‘legal conception’ (‘rechtsopvatting’) indicate. Morality was political mostly as a counterpoint to ‘intolerance’ (‘intolerantie’). In the 1980s, however, neighbours such as ‘awareness of norms’ (‘normbesef’), ‘sense of responsibility’ (‘verantwoordelijkheidsgevoel’), ‘terror’ (‘terreur’), ‘sexuality’ (‘seksualiteit’), ‘outgrowth’ (‘uitwas’), ‘egoism’ (‘egoïsme’), ‘credibility’ (‘geloofwaardigheid’) and ‘communism’ (‘communism’) point to a new political concern for crime and fraud, all caused by, in the words of a liberal politician, a blurring of moral standards brought about by the supposedly lawless and riotous 1970s.[58] The ‘diffusion of norms’ (‘normvervaging’) thus became a highly political trope in the 1980s that indicates that the concept of morality is no longer a mere description of a particular domain of individual and societal life, but refers to something that is endangered in society. This politicisation of moralistic concepts even includes a re-politicisation of concepts that had become politicised earlier in the long 1960s. ‘Society’, ‘equality’, ‘suffering’, ‘reform’ (‘hervorming’) and, to a lesser extent, ‘livability’ grew more abstract in the late 1960s, but also in the 1980s. In the latter period, they are included not in a progressive story of emancipation and democratic renewal, but in a neoliberal-communitarian one rooted in the idea of a ‘responsible society’.[59]

In sum, patterns of conducive abstraction challenge and refine established accounts of politicisation as a historical process. By demonstrating how conducive abstraction operates across issues, actors and values, I have indicated that politicisation is far more intricate than simply bringing an issue onto the parliamentary agenda. It emerges as a complex process of discursive redefinition and construction. Yet this complexity can be studied at scale. When viewed in the aggregate, distinct patterns become discernible, offering a clearer understanding of dynamics at play amidst this complexity. I have nuanced the idea of a politicising progressive decade by pointing to alternative thematic foci and the early attenuation of politicisation in the 1970s. Moreover, I have exposed the 1980s as an era of intense conducive abstraction. Neoliberal-communitarian ideology may have been branded at the time as a return to ‘businesslike’ realism, but it nonetheless appears as the source of widespread conceptual politicisation.

Plastification¶

‘We can no longer keep writing policies and experimenting. That imagination is over. We must now choose and decide based on realism and credibility’.[60] If the slogan of the 1970s was ‘power to the imagination’, Koos Rietkerk – leader of the liberal VVD in the House of Representatives – argued in October 1980, the harsh economic realities of the new decade had put an end to imaginative experiments. The 1980s warranted sobriety and pragmatism. Rietkerk was not alone in proclaiming a new era of realism. Across the political spectrum, politicians felt that the new decade required a new approach to politics. They contrasted participation with efficiency, ideals with ‘hard facts’ (‘harde feiten’), and ideology with ‘sobriety and realism’ (‘nuchterheid en werkelijkheidszin’).[61] The Lubbers cabinets are often considered the hallmarks of a new managerial style of politics that amounted to technical and obscure jargon (Illustration 3).[62] Managerialism revolves around the idea that ‘the world should and can be managed, involving ideologies informed by instrumental rationality, and techniques directed towards the control of organisations and other social outcomes’.[63] The neoliberal turn towards market solutions, privatisation and deregulation in the 1980s is often associated with these managerial ideas and styles.[64] This prompts the question whether conceptual politicisation and depoliticisation is visible in parliamentary language use, and if so, whether its temporal distribution aligns with existing understandings of pacified and neoliberal depoliticisation.

In this section, I investigate conceptual depoliticisation through the lens of plastification in order to shed light on the long-term evolution of depoliticisation in the Dutch post-war parliament. In 1988, Pörksen characterised terms as ‘information’, ‘development’, ‘system’ and ‘resource’ (‘bron’) as plastic words that transferred from scientific spheres to the popular vernacular.[65] Here, they function as abandoned metaphors: their original sphere has faded from view. ‘System’ was once a metaphor that could be used to invoke the pictorial power of the early-modern conception of the system of the universe.[66] Systems in the late twentieth century, however, have lost their scientific reference, as they seem to allude to a concrete and real, existing system. This narrated realness makes the plastic word the mirror image of a political concept and, as such, a vehicle for depoliticisation. Plastic words lack ‘the defining power, the picturesqueness, or the polemical pointedness’ of political concepts.[67] As such, they are reminiscent of the so-called condensations and reifications that often take centre stage in critical discourse analysis. Concepts such as globalisation and adjustment, as scholars have argued, are used to negate political choice by presenting political choices as natural processes.[68] They condense and collapse ‘processes, participants, and circumstances’ into concepts that are narrated as real, tangible objects and trends.[69]

Plasticity as introduced by Pörksen offers opportunities for modelling. I hypothesise that plastification appears when a concept becomes less abstract while its frequency increases. If a concept becomes more popular, but is also narrated in an increasingly concrete way, I suspect this to be an indicator of a more plastic use that hints at its presentation as a supposedly objective reality that necessitates certain political actions. For example, in 1993 the politician Wim van Gelder (PvdA) argued that globalisation ‘should lead to the conclusion that there should be greater dynamism and flexibility’.[70] His colleague Joost van Iersel (CDA) responded by arguing that globalisation required a ‘new sense of urgency’ (‘gevoel van urgentiei>’).[71] Both speakers present globalisation as an unavoidable reality that requires administrative adaption and escapes political choice and conflict. The discursive presentation of globalisation as concrete thus removes its general, abstract and potentially political character. As such, the notions of plasticity and plastification offer the chance to operationalise a specific form of conceptual depoliticisation that, refines our understanding of (de)politicisation as a historical process.

Plastic words¶

Similar to conducive abstraction, the model for plastification detects hundreds of concepts, ranging from ‘alternative’ (‘alternatief’) to ‘honesty’ (‘eerlijkheid’) and ‘stimulus’ (‘stimulans’). Figure 4 shows a selection of detected plastic words. Similar to the previous section, I first discuss several categories of plastifying terms. The first category consists of plastifying terms that signify processes. This group almost exclusively consists of lexical nominalisations such as ‘harmonisation’ (‘harmonisatie’), ‘fluctuation’ (‘fluctuatie’), ‘modification’ (‘wijziging’), ‘deflection’ (‘afwijking’), ‘decentralisation’ (‘decentralisatie’) and ‘individualisation’ (‘individualisatie’).[72] Politicians refer to political-administrative projects such as ‘decentralisation’ and ‘harmonisation’ and societal trends such as ‘automation’ (‘automatisering’) and ‘individualisation’ as processes that are undisputed and unavoidable. ‘People are not even aware that they think more in abstract concepts than in terms of actual people: “ageing”, “individualisation” and “emancipation” instead of “the elderly” and “women”’, Ria Beckers-Bruijn, leader of the Greens, aptly observed in 1985.[73] Especially in the 1980s, politicians regularly called on cabinet members ‘to adapt to developments in society such as ageing and depopulation, the socio-cultural consequences of long-term unemployment, individualisation and technologisation’.[74] This rhetoric is far removed from the ideological temporality of political abstractions. Then-director of the Scientific Bureau of the PvdA Joop Den Uyl claimed in a 1956 speech that ‘automation and the application of nuclear energy will change the place of labour in the world of tomorrow. In that world we should fight for freedom and harmony’.[75] In Den Uyl’s use of the concept, the trend of automation compelled action. Three decades later, the identification of societal trends seems to be accompanied primarily with a call for adaptation, rather than radical action.

The second, more voluminous, category of plastic words consists of terms such as ‘step’ (‘stap’), ‘goal’ (‘doel’), ‘priority’ (‘prioriteit’), ‘line’ (‘lijn’), ‘stimulus’, ‘signal’ (‘signaal’) and ‘foundation’ (‘fundament’). This vocabulary appears to signify metaphorical ‘objects’ used in political rhetoric to manage policymaking.[76] They are marked by two distinctive features: metaphoricity and managerialism. First, many of these words enter the parliamentary lexicon as metaphors. The relatively high degree of abstractness of a word such as ‘line’ in 1950 – stemming from phrases such as ‘the general line of our politics’ – betrays its original metaphorical character.[77] The ability of the word to connect to disparate realms reflects in high abstractness scores. However, a persistent decline in abstractness (‘line’ drops from 0.76 to 0.5 between 1950 and 1976) confirms Pörksen’s idea that plastic words abandon their metaphorical connection between spheres. Similar to words such as ‘course’ (‘koers’), ‘compass’ (‘kompas’), ‘signal’, ‘injection’ (‘injectie’), ‘analysis’ (‘analyse’) and ‘wavelength’ (‘golflengte’), the concept ‘line’ has become a real tangible object. If managerialism amounts to instrumental rationality and organisational control, the surging use of ‘plotting lines’ (‘lijnen uitzetten’), ‘following compasses’ (‘kompas volgen’) and ‘laying foundations’ (‘basis leggen’) is a case in point. Terms such as ‘methodology’ (‘methodologie’), ‘analysis’ and ‘model’ (‘model’) are used to present contingent political processes as scientific ones that leave little room for conflict. Others (‘compass’, ‘trajectory’) invoke a similar sense of managerial stability and direction by harnessing the vocabulary of transportation.

The third category of plastifying terms appears as a subcategory of the (formerly) metaphorical objects. It stands out as a consistent group because its constituent terms all directly refer to democratic decision-making. Surprisingly, ‘debate’ (‘debat’), ‘discussion’ (‘discussie’), ‘idea’ (‘idee’), ‘principle’ (‘principe’), ‘vision’ (‘visie’) and ‘alternative’ increase in frequency but decline in abstractness. The example of ‘alternative’ shows what happens to the meaning and use of these terms. In 1948, ‘alternative’ is semantically surrounded by ‘prospect’ (‘vooruitzicht’), ‘criterion’ (‘criterium’), ‘choice’ (‘keus’), ‘goal’, ‘novelty’ (‘novum>’), ‘dilemma’ (‘dilemma’), ‘ideal’ (‘ideaal’), ‘imperialism’ (‘imperialisme’) and ‘communism’. In 1968, the liberal politician Cees Berkhouwer adhered to such an abstract understanding when, referring to the Second World War, he argued that ‘now, thirty years later, we are faced with the global – in the literal sense of the word – alternative of living together or dying together in an all-destroying chaos of nuclear explosions’.[78] Thirty years later, by contrast, talk of alternatives was less about existential matters such as peace or annihilation. In 1986 its neighbourhood features ‘variant’ (‘variant’), ‘option’ (‘optie’), ‘policy alternative’ (‘beleidsalternatief’), ‘building block’ (‘bouwsteen’), ‘model’, ‘coverage potential’ (‘dekkingspotentieel’), ‘coverage proposal’ (‘dekkingsvoorstel>’) and ‘scenario’ (‘scenario’). In the late twentieth century, politicians spoke of ‘alternatives’ not as comprehensive positive or negative visions of a future world, but as policy options and variants that, moreover, ought to be responsible, reasonable and financially feasible. Plastification thus also records a shift in language whereby democratic decision-making was ‘rationalised’. Politics, it seems, was increasingly imagined as a rationalised assembly line.

The fourth and last category of plastifying terms concerns those that pertain to values. ‘Carefulness’ (‘voorzichtigheid’), ‘expertise’ (‘deskundigheid’), ‘clarity’ (‘duidelijkheid’), ‘integrity’ (‘integriteit’), ‘honesty’ (‘>=eerlijkheid’) and ‘completeness’ (‘volledigheid’) show increasing frequency and decreasing abstractness. They appear markedly different from, for example, ‘equality’ and ‘transparency’ – values that were directed towards societal or democratic reform and improvement. Rather than exponents of morality or ideology, plastic values such as ‘expertise’ and ‘completeness’ seem to assume the form of more technical criteria applied to parliamentary procedures. In 1950, ‘clarity’ is similar to ‘respect’ (‘respect’), ‘candour’ (‘openhartigheid’) and ‘decisiveness’ (‘beslistheid’). Three decades later, it is associated with ‘clarification’, ‘unclarity’ and ‘certainty’ (‘zekerheid’). This reveals a shift from ‘clarity’ as a moral virtue to ‘clarity’ as something detached from individuals and pursued as a stand-alone object. The increased concreteness derives from the idea that clarity is a tangible artefact or a sensible situation. Clarity should exist; it should be ‘acquired’, ‘supplied’ and ‘created’.[79]

The four categories of plastic words point to the diversity of conceptual depoliticisation in parliament. Nominalised processes generate necessity; abandoned metaphors enforce control; ‘priorities’ and ‘alternatives’ rationalise political choice; and plastic values redirect normativity from societal reform to procedural correctness. If conducive abstraction underscores the diversity of conceptual politicisation, plastification points to various manifestations of depoliticisation. Again, we can take this ability of the model to detect individual instances of depoliticisation to offer a diachronic perspective.[80]

Plastification as process¶

Similar to conducive abstraction, the terms identified as subject to plastification can also be studied in the aggregate. Calculating the density of plastification allows us to better understand its historical development. Figure 3 shows the result of counting the amount of words that are plastifying in every time period. The density signal appears remarkably gradual compared to conducive abstraction; it is more even and lacks pronounced peaks. Only the late 1970s appear relatively ‘dense’ in plastification. Moreover, the frequency panel at the bottom right indicates a highly consistent increase in frequency of most plastifying terms. Terms subject to conducive abstraction fluctuate in frequency, but the vast majority of plastic words display a continuous increase in frequency. These observations invalidate the idea of depoliticisation as a remnant of a sudden managerial rupture around 1980. The question is, however, what explains the process of plastification in the House of Representatives and its imprint on parliamentary language?

Policy, politics and procedure¶

The frequency and abstractness signals for plastic terms visible in Figure 3 show that plastification was a gradual process. Many terms consistently increase in frequency and decrease in abstractness over the span of decades. This longer-term character of plastification leads back to the 1950s as a moment when many terms started their increase in frequency and decrease in abstractness. About 30 percent of all plastic words detected start their process of plastification before 1955. Many of these early plastifications are managerial metaphors, discussed as the second and third categories in the previous section. ‘Priority’, ‘alternative’, ‘instrument’ (‘instrument’), ‘course’, ‘step’, ‘term’ (‘termijn’), ‘idea’, ‘discussion’, ‘nuance’ (‘nuance’) and ‘hesitation’ (‘aarzeling’) all plastify in the 1950s. This onset of plastification in the 1950s challenges the common emphasis in historiography on the 1980s as a time of managerial takeover. Managerial words do not follow sudden ideological changes, but something more structural and deeply rooted.[81]

What then explains the surprisingly deep roots of plastification? I argue that we should interpret plastification as driven by policymaking. Historians and political theorists have argued for understanding policy as a specific topos of the political and a distinctively twentieth-century phenomenon. Defining policy as ‘regulated politicking’ and ‘a complex of inclusion and coordination of measures into a project’, historian and political theorist Kari Palonen points to the differences between policy and other topoi of the political such as deliberation or judgement. Policymaking revolves around teleology and the regulation of activities; it adheres to the functional rationality of administration rather than the value rationality of ideological politics.[82] Policy, moreover, is distinctively post-war. In the 1950s, the number of ‘policy areas’ grew in number. In the 1960s and 1970s, parliament was increasingly busy with deliberating over ‘policy documents’ (‘notas’) that differed from other procedural forms, such as the yearly budget debates and legislative debates.[83]

I consider the emergent plastic words as the linguistic reflection of this post-war turn to policy. The idea of policy as rationalised administration, regulation and management is reflected in the increasing concrete use of terms such as ‘foundation’, ‘priority’, ‘alternative’ and ‘variant’ (‘variant’). The linearity and teleology of policy is visible in the use of words such as ‘trajectories’ (‘trajecten’), ‘goalposts’ (‘doelpalen’) and ‘lines’. Syntactically, the link between plastic words and policy is manifest in the fact that almost every plastic word from the second and third category is paired with ‘policy’. Politicians increasingly speak of ‘policy lines’ (‘beleidslijnen’), ‘policy priorities’ (‘beleidsprioriteiten’) and ‘policy alternatives’ (‘beleidsalternatieven’). Thinking in terms of policy appears to require metaphors that express teleology and regulation. As policy areas fixed themselves in the parliamentary imagination as objective realities, the language of policy lost its metaphoricity: it became plastic.

The idea of policy-induced plastification also explains the small but significant bump in density in the late 1970s. Another 30 percent of plastic terms become more concrete in the decade between 1968 and 1978. As discussed in the section on conducive abstraction, this period witnesses a transition from political abstraction to an apparent translation of politicised issues, actors and values into policymaking or governmental politicisation. After ‘open-air recreation’ (‘openluchtrecreatie’) grows more abstract in the late 1960s, it grows more concrete in the 1970s, as it becomes enmeshed in the more technical and seemingly concrete language of policy. This turn to the concrete seems to occur not only at the end of periods of conducive abstraction, but also in a new era of plastification. In other words, the 1970s are not only defined by the absence of conducive abstraction, but also by the presence of new plastic words. Language related to the deliberation over policy in parliament tends to become more concrete in the mid-1970s. Examples include ‘concretisation’ (‘concretisering’), ‘effort’ (‘inspanning’), ‘evaluation’ (‘evaluatie’), ‘test’ (‘toets’) and ‘result’ (‘resultaat’).

Policy thus appears as the driving factor behind the increasing popularity of ostensibly managerial and rational plastic words in the House of Representatives. At the same time, policy also sheds light on the peculiar plastification of terms related to debate itself (such as ‘discussion’ and ‘vision’) and the peculiar plastic values that rise in popularity. I argue that in the 1970s and 1980s, parliament was increasingly concerned with procedural correctness in policymaking. In her study on Dutch parliamentary rules and customs, historian Carla Hoetink notes that self-reflection became an important value for parliamentarians in the 1980s.[84] Already in the 1970s, issues around administrative transparency had led to proposals for procedural reform. In the mid-1980s, the so-called RSV affair – a scandal around the Rijn-Schelde-Verolme conglomerate that, despite billions of guilders in state subsidies, went bankrupt in 1983 – sparked further debate about the best way to organise parliament.[85] I take these moments of reflection as explicit articulation of a more substantial shift in parliamentary debate towards procedural correctness and fairness.

Put simply, Dutch politicians increasingly focused on managing the process of policymaking rather than on ideological contestation about the underlying goals of politics. The changing texture of parliamentary language can be interpreted as a shift from debating input to administering output. The depoliticising quality of plastic words seems correlated to this long-term reorientation of parliamentary politics. The plastification and increasing popularity of ‘efficiency’, ‘clarity’, ‘expertise’ and ‘wisdom’ should be understood as the prioritisation of procedural concerns. These concerns were expressed as more concrete than ideological or moral ideals and goals. Politicians spoke about mobilising expertise, providing clarity and guaranteeing effectiveness. The exception that proves the rule is ‘quality’ (‘kwaliteit’) – a term whose frequency and abstractness grow continuously until the end of the period under study. In other words, almost all values except ‘quality’ become more plastic. I interpret this as the confirmation that political debate increasingly turned to optimising, managing and assessing output. Politics became plastic – shaped by policy procedures and the pursuit of optimal outcomes, exalting precision and efficiency and cloaked in language that invoked inevitability.

The model of plastification leads to a wide range of concepts, from ‘vision’ to ‘expertise’. They reveal the complexity of conceptual depoliticisation. They show that depoliticisation should not (only) be understood as the absence of politics, but as the presence of concepts and arguments that revolve around necessity. Moreover, depoliticisation as a historical process appears not to be prompted by a sudden turn to managerial neoliberalism, but unfolds gradually as the consequence of policymaking as an increasingly central topos in parliamentary politics. When Joop den Uyl argued in 1978 that a ‘grey cloak’ of depoliticisation was spreading over the country, he was wrong. Woven with threads of plastic, the cloak had been spreading for quite some time already.

Conclusion¶

In this article, I used computational text analysis to study discursive politicisation and depoliticisation in post-war Dutch parliamentary debate. Building on theories from conceptual history, I have studied conducive abstraction and plastification as forms of conceptual politicisation and depoliticisation. I constructed models that allowed me to trace these processes at the level of words, pointing to, for example, the increasingly political use of a word such as ‘minority’ and the expression of ‘signal’ as a seemingly concrete object that enforced necessity. My approach also allowed me to study these processes at scale. By aggregating trends, conducive abstraction and plastification were identified as accelerating in some periods, and decelerating in others.

As such, I cast a different light on post-war (de)politicisation. I showed that, from a parliamentary and conceptual perspective, the politicisation of a progressive decade revolved to an important extent around economic policy issues. It also ended surprisingly early, as the plasticity of policy supplanted conducive abstraction in the early 1970s. The ensuing decade, often identified as a return of depoliticisation, proved surprisingly political in my analysis. The rise of neoliberalism brought intense politicisation, embedding financial and Christian Democratic communitarian ideas into ideological narratives. Contrary to scholarship that views politicisation and depoliticisation as mutually exclusive, I also showed that the conducive abstraction of the 1980s ran parallel to the unprecedented popularity of plastic words. Plastic objects, processes and values gradually but decisively populate the language of the House of Representatives in the post-war era. As artefacts of policymaking, they rationalise politics and express the primacy of procedural correctness and output legitimacy. As such, they leave a lasting imprint on parliamentary debate, as their continuous increase in frequency shows.

My account of conceptual (de)politicisation is by no means definitive. Extending the period under study backwards into the nineteenth century and forwards into the twenty-first might reveal different dynamics. It would be interesting to investigate how plastic politics fares under the populist winds that gathered soon after 1994. Moreover, contextual embedding techniques such as BERT and GPT offer the possibility of detecting plasticity and abstraction at an ever finer-grained level, which allows their examination at the level of individual politicians and parties.

While my account of conceptual (de)politicisation is not definitive, extending the scope of analysis – both temporally and methodologically – opens exciting new avenues for research. This article demonstrates that incorporating discourse and culture into (political) history does not require a focus on micro-level narrative reconstruction. Instead, the availability of large datasets and advancements in computational methods enable historians to analyse history, politics and culture as processes, dynamics and systems. This approach demands more than just applying a digital tool; it requires carefully constructing models and theories that can guide, but do not necessarily depend on, quantitative operationalisation.[86] With these models, we do not have to pick a side between ‘close’ and ‘distant’ reading, but we can think about history in a more formalised and systematic way and hopefully answer bigger and better questions about the (political) past.

[1] I would like to thank Melvin Wevers, Henk te Velde, Diederik Smit, the editorial board of BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful theoretical feedback on earlier versions of this article. I am also grateful to Pasi Ihalainen, Jani Marjanen and Simon Specht for their valuable recommendations on relevant literature and theory.

[2] Original: ‘Ontplooiing, zorgvuldigheid, gerechtigheid. Wees daar maar eens tegen. Je kunt er van alles bij denken en dat maakt het in een depolitiseringsfilosofie juist zo bruikbaar’. Handelingen Tweede Kamer (HTK), 17 January 1978, 348. All translations of quotes are my own.

[3] As argued in Dries van Agt’s ‘government declaration’; see HTK, 16 January 1978, 332.

[4] Original: ‘keuzen te ontwijken, reële tegenstellingen toe te dekken’. HTK, 17 January 1978, 349.

[5] HTK, 17 January 1978, 348.

[6] Colin Hay, Why We Hate Politics (Cambridge University Press 2007) 79.

[7] Peter Burnham, ‘New Labour and the Politics of Depoliticisation’, The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 3:2 (2001) 128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.00054; Matt Wood and Matthew Flinders, ‘Rethinking Depoliticisation: Beyond the Governmental’, Policy & Politics 42:2 (2014) 161. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655909.

[8] Arend Lijphart, Verzuiling, pacificatie en kentering in de Nederlandse politiek (Athenaeum Boekhandel Canon 1968) 122.

[9] Piet de Rooy, Alles! En wel nu! Een geschiedenis van de jaren zestig (Wereldbibliotheek 2020) 33-37.

[10] Hans Daalder, Politisering en lijdelijkheid in de Nederlandse politiek (Van Gorcum 1974) 47-53.

[11] Gerd Koenen, Das rote Jahrzehnt: Unsere kleine deutsche Kulturrevolution 1967-1977 (Kiepenheuer & Witsch 2001); Antoine Verbij, Tien rode jaren: Links radicalisme in Nederland: 1970-1980 (Ambo|Anthos 2005).

[12] Carla van Baalen and Anne Bos (eds.), Grote idealen, smalle marges: Een parlementaire geschiedenis van de lange jaren zeventig 1971-1982 (Boom 2022) 24-34; Duco Hellema, Nederland en de jaren zeventig (Boom 2012) 189-193.

[13] Merijn Oudenampsen, ‘Between Conflict and Consensus: The Dutch Depoliticized Paradigm Shift of the 1980s’, Comparative European Politics 18:5 (2020) 771-792. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00208-3; Jouke Turpijn, 80s dilemma: Nederland in de jaren tachtig (Bert Bakker 2011) 65-68.

[14] Herman De Liagre Böhl, ‘Consensus en polarisatie. Spanningen in de verzorgingsstaat. 1945-1990’, in: Remieg Aerts et al., Land van kleine gebaren. Een politieke geschiedenis van Nederland 1780-1990 (SUN 1999) 331.

[15] For a qualification of the 1980s as a return of pragmatism and pacification, see Friso Wielenga, Op zoek naar stabiliteit: Nederland tijdens de Balkenende-jaren 2002-2010 (Boom 2022) 27; Joop Van den Berg, Stelregels en spelregels in de Nederlandse politiek (Samsom H.D. Tjeenk Willink 1990) 10-13.

[16] See, for example, Paul Pennings and Hans Keman, ‘The Changing Landscape of Dutch Politics Since the Seventies: A Comparative Exploration’, Acta Politica 43:2-3 (2008) 154-179. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2008.4; Sjoerd Keulen, Monumenten van beleid. De wisselwerking tussen Nederlands rijksoverheidbeleid, sociale wetenschappen en politieke cultuur, 1945-2002 (Uitgeverij Verloren 2014) 13; Philip van Praag, ‘Hoe uniek is de Nederlandse consensusdemocratie?’, in: Philip van Praag and Uwe Becker (eds.), Politicologie. Basisthema’s en Nederlandse politiek (Spinhuis/Maklu 2008) 288; Maarten Prak and Jan Luiten van Zanden, Nederland en het poldermodel. sociaal-economische geschiedenis van Nederland, 1000-2000 (Bert Bakker 2013) 230-231.

[17] Paolo Pombeni, ‘Political History. An Overview or the Tortuous Path of Political History’, Ricerche Di Storia Politica (2017) 7-14.

[18] See, for example, Maartje Janse, ‘“What Value Should We Attach to All These Petitions?”: Petition Campaigns and the Problem of Legitimacy in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands’, Social Science History 43:3 (2019) 509-530. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2019.18; Anne Petterson, ‘Competing Models of Political Debate: Popular Representation in the Late Nineteenth-Century Meeting Hall’, International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 12:3 (2024) 275-294. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/22130624-20240006.

[19] John Lawrence, ‘Political History’, in: Stefan Berger et al. (eds.), Writing History: Theory and Practice (Oxford University Press 2003), 183-191; Giovanni Orsina, ‘Perfectionism Without Politics. Politicisation, Depoliticisation, and Political History’, Ricerche Di Storia Politica 20 (2017) 75-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1412/87621; Willibald Steinmetz and Heinz-Gerhard Haupt, ‘The Political as Communicative Space in History: The Bielefeld Approach’, in: Willibald Steinmetz et al. (eds.), Writing Political History Today (Campus Verlag 2013) 11-30; Thomas Mergel, ‘Cultural Turns and Political History’, Ricerche Di Storia Politica 20 (2017) 33-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1412/87617.

[20] Adriejan van Veen and Theo Jung (eds.), Depoliticisation before Neoliberalism: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political in Modern Europe (Palgrave Macmillan 2025). This turn to discourse is also noticeable in political science research on (de)politicisation. See Wood and Flinders, ‘Rethinking Depoliticisation’, 151-170.

[21] Peter Van Dam, ‘Een wankel vertoog. Over ontzuiling als karikatuur’, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review (hereafter BMGN – LCHR) 126:3 (2011) 70-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.7380.

[22] Hans Blom, ‘“De jaren vijftig” en “de jaren zestig”’, BMGN – LCHR 112:4 (1997) 517-526. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.4571; James C. Kennedy, Nieuw Babylon in aanbouw: Nederland in de jaren zestig (Boom 1997) 27-28; Bram Mellink, ‘Tweedracht maakt macht. De PvdA, de doorbraak en de ontluikende polarisatiestrategie (1946-1966)’, BMGN – LCHR 126:2 (2011) 33-35. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.7309.

[23] Bram Mellink, ‘Towards the Centre: Early Neoliberals in the Netherlands and the Rise of the Welfare State, 1945-1958’, Contemporary European History 29:1 (2020) 30-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777318000887; Bram Mellink and Merijn Oudenampsen, Neoliberalisme. een Nederlandse geschiedenis (Boom 2022).

[24] Henk te Velde, ‘Introductie’, in: Dennis Bos et al. (eds.), Harmonie in Holland. Het poldermodel van 1500 tot nu (Boom 2008) 9-29; Van Dam, ‘Een wankel vertoog’, 55.

[25] Peter van Dam et al., ‘Introductie’, in: Peter Van Dam et al. (eds.), Onbehagen in de polder. Nederland in conflict sinds 1795 (Boom 2014) 7-19.

[26] See for example: Harm Kaal, ‘Popular Politicians: The Interaction Between Politics and Popular Culture in the Netherlands, 1950s-1980s’, Cultural and Social History 15:4 (2018) 595-616. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14780038.2018.1492787.

[27] Henk te Velde, ‘Politieke cultuur en politieke geschiedenis’, Groniek 137 (1997) 393-395.

[28] Lawrence, ‘Political History’, 194.

[29] Luke Blaxill, The War of Words: The Language of British Elections, 1880-1914 (Boydell & Brewer 2020) 6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787446205.

[30] For common pitfalls in current scholarship on (de)politicisation, see Bob Jessop, ‘Repoliticizing Depoliticization: Theoretical Preliminaries on some Responses to the American Fiscal and Eurozone Debt Crises’, Policy & Politics 42:2 (2014) 207-223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655864.

[31] This concerns mostly the period before 1960. Between 1960 and 1994, about 25 percent of the speeches used for this study are delivered in committee meetings.

[32] Christopher Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti, Technopopulism: The New Logic of Democratic Politics (Oxford Academic 2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198807766.001.0001; Anton Jäger, Hyperpolitiek. Extreme politisering zonder politieke gevolgen (Athenaeum 2024).

[33] See, for example, assessments of the 2010s as the ‘reinvention of consensus politics’, in Simon Otjes and Tom Louwerse, ‘The reinvention of consensus politics: governing without a legislative majority in the Netherlands 2010-2021’, Acta Politica 59 (2024) 797-821. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00310-w; and calls for a return to Den Uyl’s strategy of polarisation as a way of furthering open debate in Femke Halsema, ‘De open samenleving en haar bondgenoten’, Machiavellilezing, 14 February 2024, https://www.amsterdam.nl/bestuur-organisatie/college/burgemeester/speeches/open-samenleving-bondgenoten/.

[34] Reinhart Koselleck and Michaela Richter, ‘Introduction and Prefaces to the Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: (Basic concepts in history: A historical dictionary of political and social language in Germany)’, Contributions to the History of Concepts 6:1 (2011) 13-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3167/choc.2011.060102.

[35] Uwe Pörksen, Plastic Words: The Tyranny of a Modular Language (Pennsylvania State University Press 2010) 20-23.

[36] Melvin Wevers and Marijn Koolen, ‘Digital begriffsgeschichte: Tracing Semantic Change Using Word Embeddings’, Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 53:4 (2020) 226-224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2020.1760157; Kristoffer L. Nielbo et al., ‘Quantitative Text Analysis’, Nature Reviews Methods Primers 4:25 (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-024-00302-w.

[37] Nikhil Garg et al., ‘Word Embeddings Quantify 100 years of Gender and Ethnic Stereotypes’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:16 (2018) E3635-E3644. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1720347115.

[38] Original: ‘Het zal een ieder wel duidelijk zijn, dat wat vroeger onder inspraak werd verstaan een inspraak was zonder dat er zelfs een woord werd gesproken: de inspraak van het hart, van het geweten, van de natuur, van de haat, van de liefde. Het waren allemaal inspraken, waarbij niet werd gesproken. Het nieuwe begrip inspraak is in de woordenboeken nog niet gedefinieerd’. HTK, 11 December 1968, 1033.

[39] The argument for participation is often associated with the Dutch ‘New Left’ movement that was part of the Social Democratic Party. See Hans van den Doel et al., Tien over rood: uitdaging van Nieuw Links aan de PvdA (Polak & Van Gennip 1966) 18.

[40] Claudia Mazzuca and Matteo Santarelli, ‘Making It Abstract, Making It Contestable: Politicization at the Intersection of Political and Cognitive Science’, Review of Philosophy and Psychology 14 (2023) 1257-1278. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-022-00640-2.

[41] Christian Geulen, ‘Plädoyer für eine Geschichte der Grundbegriffe des 20. Jahrhunderts’, Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 7:1 (2010) 79-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1790; Willibald Steinmetz, ‘Some Thoughts on a History of Twentieth-Century German Basic Concepts’, Contributions to the History of Concepts 7:2 (2012) 87-100.

[42] Wood and Flinders, ‘Rethinking Depoliticisation’, 154.

[43] See, for example, HTK, 12 January 1971, 2149.

[44] See, for example, HTK, 14 June 1977, 29.

[45] HTK, 1 December 1965, C-642.

[46] See, for example, debates over Moluccan and Surinamese groups: HTK, 26 June 1974, 4357; HTK, 21 June 1976, 1134.

[47] HTK, 11 December 1957, 3423; HTK, 22 October 1957, 278.

[48] HTK, 21 May 1968, 2124.

[49] Original: ‘De wetgeving is veel te ingewikkeld geworden en nauwelijks op uitvoerbaarheid getoetst. Onvoldoende controle heeft geleid tot een wildgroei aan subsidies en gesubsidieerde instellingen’. HTK, 17 November 1981, 384.

[50] For the historiographical debate over periodisation, see Hans Righart, De eindeloze jaren zestig. Geschiedenis van een generatieconflict (Singel Uitgevers 1995) 265-267; Joop Ellemers, ‘De jaren zestig in Nederland. Een geval van verlate modernisering?’, Sociologische Gids 44:5-6 (1997) 409-420; James C. Kennedy, ‘New Babylon and the Politics of Modernity’, Sociologische Gids 44:5-6 (1997) 361-374; Niek Pas, ‘De problematische internationalisering van de Nederlandse jaren zestig’, BMGN – LCHR 124:4 (2009) 618-632. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.7050.

[51] Mellink and Oudenampsen, Neoliberalisme, 82-92.

[52] Colin Hay, ‘Depoliticisation as Process, Governance as Practice: What Did the “First Wave” Get Wrong and Do We Need a “Second Wave” to Put It Right?’, Policy & Politics 42:2 (2014) 293-311. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1332/030557314X13959960668217.

[53] Original: ‘De studenten van de jaren ‘60 zijn de notaschrijvers en innovatiebedrijvers van de jaren ‘70’. HTK, 21 November 1979, 1420.

[54] Turpijn, 80s dilemma, 41-46.

[55] See, for example, HTK, 30 January 1985, 18.

[56] For a discussion on models of economic policy change, see Oudenampsen, ‘Between conflict’, 771-792.

[57] Merijn Oudenampsen, ‘Neoliberal Sermons: European Christian Democracy and Neoliberal Governmentality’, Economy and Society 51:2 (2022) 330-352. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2022.1987743.

[58] HTK, 2 September 1985, 14.

[59] The 1987 CDA manifesto put the concept of the ‘responsible society’ at the centre of the new ideological course of the Christian Democrats. See Gerrit Voerman and Paul Lucardie, ‘Ideologie en individualisering. De grondslagendiscussie bij CDA, PvdA en VVD’, Beleid en Maatschappij 19:1 (1992) 31-34.

[60] Original: ‘Wij kunnen niet meer nota’s blijven schrijven en blijven experimenteren. Die verbeelding is voorbij. Wij moeten nu kiezen en beslissen op basis van werkelijkheidszin en geloofwaardigheid’. HTK, 7 October 1980, 141.

[61] HTK, 18 April 1985, 4537; HTK, 26 April 1982, 38; HTK, 23 November 1982, 662.

[62] Kroeze and Keulen, ‘Managerpolitiek’, 102-105; Jouke de Vries, Paars en de managementstaat. Het eerste kabinet-Kok (1994-1998) (Garant 2002) 19-21.

[63] Matthew Eagleton-Pierce and Samuel Knafo, ‘Introduction: The Political Economy of Managerialism’, Review of International Political Economy 27:4 (2020) 768. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1735478. Also see: Thomas Klikauer, ‘Managerialism as Ideology’, in: Thomas Klikauer (ed.), Managerialism: A Critique of an Ideology (Palgrave Macmillan 2013) 24-44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137334275_2; Tony J. Watson, ‘Managers, Managism, and the Tower of Babble: Making Sense of Managerial Pseudojargon’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language 166 (2004) 67-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2004.015.

[64] Ronald Kroeze and Sjoerd Keulen, ‘The Managers’ Moment in Western Politics: The Popularization of Management and Its Effects in the eighties and 1990s’, Management & Organizational History 9:4 (2014) 394-413. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2014.989235.

[65] Pörksen, Plastic Words, 18.

[66] Clifford Siskin, System: The Shaping of Modern Knowledge (MIT Press Scholarship Online 2017) 68-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262035316.001.0001.

[67] Pörksen, Plastic Words, 45.

[68] Roger Fowler, Language in the News: Discourse and Ideology in the Press (Routledge 1991) 79-81; Bernard J. McKenna and Philip Graham, ‘Technocratic Discourse: A Primer’, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 30:3 (2000) 223-251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2190/56FY-V5TH-2U3U-MHQK; Franco Moretti and Dominique Pestre, ‘Bankspeak: The Language of World Bank Reports’, New Left Review 92:2 (2015) 75-99; Yiannis Mylonas, ‘The “Greek Crisis” as a Middle-Class Morality Tale: Frames of Ridicule, Pity and Resentment in the German and the Danish Press’, Continuum 32:6 (2018) 770-781. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1525924; Sean Phelan, ‘The Discourses of Neoliberal Hegemony: The Case of the Irish Republic’, Critical Discourse Studies 4:1 (2007) 29-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900601149459.

[69] Original: ‘Alle discussies over globalisering, de trends in brede zin, leiden tot de conclusie dat er sprake moet zijn van een grotere dynamiek en flexibiliteit’. HTK, 2 November 1993, 1402.

[70] Jay L. Lemke, Textual Politics: Discourse and Social Dynamics (Routledge 1995) 61-65.

[71] HTK, 2 November 1993, 1400.

[72] Lexical nominalisations are nouns derived from other lexical categories, most notably verbs. See Rochelle Lieber, ‘Nominalization: General Overview and Theoretical Issues’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics (2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.501.

[73] Original: ‘Men is zich er zelfs niet van bewust dat men meer in abstracte begrippen denkt dan in mensen: “vergrijzing”, “individualisering” en “emancipatie” in plaats van “ouderen” en “vrouwen”’. HTK, 15 October 1985, 469.

[74] Original: ‘(...) aan te passen aan ontwikkelingen in de samenleving, vergrijzing en ontgroening, de sociaal-culturele gevolgen van langdurige werkloosheid, individualisering en technologisering’. HTK, 22 November 1988, 1475.