Placing Value in Domestic Interiors¶

3D Spatial Mapping of Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker’s Home Art Collection¶

BMGN — Low Countries Historical Review | Volume 139-2 (2024) | pp. 4-37 | DOI: 10.51769/bmgn-lchr.13880

Weixuan Li and Chiara Piccoli

Series Digital History¶

This article is part of a series on digital history in the Netherlands and Belgium. Eleven years after the publication of the widely-read BMGN-issue on digital history in 2013 (read here), this series aims to provide a new state of the field. It comprises four serially published articles, which collectively emphasise the diversity of researchers, questions, methods and techniques that define digital history in 2024. The articles are published online in a new, HTML-based format that better showcases the methods and visualisations of the research published here. Please scan the QR-code to navigate to the HTML-version of this article.

Serie digitale geschiedenis¶

Dit artikel is onderdeel van een serie over digitale geschiedenis in Nederland en België. Elf jaar na het veelgelezen BMGN-nummer over digitale geschiedenis uit 2013 (hier te lezen) maken we een nieuwe tussenstand op. De serie bestaat uit vier serieel gepubliceerde artikelen, die tezamen de veelzijdigheid accentueren van de onderzoekers, de vragen, de methoden en technieken die anno 2024 digitale geschiedenis definiëren. Deze artikelen worden online in een nieuw, op HTML gebaseerd format gepubliceerd, waardoor de methodologische toelichting en visualisaties van het hier gepubliceerde onderzoek beter tot hun recht komen. Door de QR-code te scannen komt u meteen bij de HTML-versie van dit artikel.

Table of contents¶

- Introduction

- The house and painting collection of Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker: sources for a reconstruction

- Placing values: the distribution of artworks by their monetary worth in the Herengracht house

- Displaying status: Symbolic value of paintings and interior decoration

- A personal touch: Emotional value of paintings in private bedrooms

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

Introduction[1]¶

Every day, tens of thousands of visitors flock to admire Dutch art in museums, with many of the most cherished pieces originating from seventeenth-century Amsterdam. These artworks, mostly paintings, are often removed from their original setting and from their intended use, as many were made for and enjoyed in contemporary private homes. Within these domestic spaces, artworks, like other material artefacts, did not exist in isolation. Rather, studies on early modern European societies have shown that their emplacement within interior spaces and their interrelations with adjacent objects defined their functions, symbolic importance, and social implications.[2] The rich spatial context defining where, how, and with what artworks were displayed and used in private domestic interiors in the early modern period not only reveals the function of artworks at home, it also offers insight into the lived experience of art in everyday life. This understanding of the function and experience of art within the private domestic sphere can, in turn, change our appreciation and valuation of the early modern paintings we admire in museum collections and beyond. Yet, this intricate interplay between the space and art in early modern houses remains largely underexplored.

How did domestic spaces contribute to the value of paintings on display? Despite remarkable progress in our knowledge about visual and material culture in early modern Europe, the spatial arrangement of art in domestic settings is still superficially understood. The ‘spatial turn’ in history and art history has yet to reach the domestic realm. Art historians have long recognised that the aesthetic, political, and social significance of early modern art was contingent on its physical surroundings and spatial relationships. Nonetheless, the burgeoning ‘art in context’ research – studying relationships between works of art and their original environments – predominantly targets institutional spaces, such as palaces, city halls, and churches, or the grand residences of the nobility and elite across Europe, such as Italian palazzi and villas or English castles and country houses.[3]

In the Low Countries, existing research has delved into burghers’ houses. These studies, however, usually consider the settings of artworks as isolated spaces without a comprehensive understanding of their exact place and function within the interior space.[4] Admittedly, reconstructing the spatial arrangements of early modern domestic interiors is difficult. Often the transformations of the urban fabric over the centuries have erased some, if not all, physical evidence of early modern houses, leaving scholars with the only option of analysing archival materials. Researching archival documents, however, presents significant challenges. Even for the inventories that were drawn up by room, some rooms can be difficult to identify. Rooms may be described based on some typifying features (e.g., their colour or size) or on their function (e.g., a library) which does not provide any clues about where they were located within the house.

Next to the challenging sources, existing scholarship has yet to develop appropriate methodologies that allow capturing the spatial dimension of interiors and experimenting with measurements and volumes to recompose a house’s internal arrangement. Thus far, most researchers did this by imagining the rooms and objects that are recorded in inventories to ‘furnish in their mind a home’, while others sketched the plan of the house on paper.[5] Both approaches, however, make it difficult to perform analyses and quantifications. Therefore, in this contribution, we propose a spatial reading of inventories enhanced by a 3D visualisation to capture the interplay between place and value in domestic interiors.

Specifically, we delve into the house of Amsterdam patrician Pieter de Graeff (1638-1707) and his wife Jacoba Bicker (1640-1695), and analyse their painting collection therein. The De Graeff’s and the Bicker’s were among the most influential families in seventeenth-century Amsterdam. Together they held significant political power, effectively controlling the city government for about half a century until the Rampjaar (‘Disaster Year’) of 1672 swept away their political ambitions. Pieter was the son of burgomaster Cornelis de Graeff (1599-1664), director of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Lord of Zuid-Polsbroek, and Catharina Hooft (1618-1691), Lady of Purmerland and Ilpendam after Maria Overlander, widow of Frans Banninck Cocq. Pieter inherited these titles after his brother Jacob died in 1690, thus becoming Lord of Zuid-Polsbroek, Purmerland and Ilpendam. Jacoba Bicker was the daughter of the affluent merchant Jan Bicker (1591-1653) and Agneta de Graeff van Polsbroek (1603-1656; Pieter’s aunt). Jacoba’s sister, Wendela, married Johan de Witt (1625-1672), who became a close friend and political ally to his brother-in-law Pieter de Graeff. The long-lasting friendship between De Graeff and De Witt is evident from the letters that they exchanged.[6] The choice of this house as our case study is given by the exceptional combination of sources (discussed in the next section) which allows us to gain a holistic view of the original domestic settings and to contextualise the artworks in the rooms where they were hung.

The 3D reconstruction of Pieter and Jacoba’s house and the spatial reading of the inventory offer a unique opportunity to re-evaluate the behaviours, motivations, and values of the elite class and their culture visible from the interior decoration of their homes. Existing studies on elite culture have already sketched their choices and behaviours regarding their art collections and other possessions at home. Scholars have shown that the upper crust of society was fully aware of the importance of status symbols and had a notable preference for portraits above all genres.[7] Their residences contributed to the status display: in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, the urban elites often resided in imposing houses along the prestigious canal ring.[8] These existing studies, albeit insightful, have not discussed interior spaces. In particular, it is unclear how the status symbols and preferences for portraits were incorporated into the interior decorations. How did the urban elite arrange their domestic spaces so that such symbolic functions served alongside their everyday needs? How did the place in interior spaces affect the appreciation of the paintings? Answering these questions will not only expand our knowledge about elite culture but also helps us better understand the functions of paintings and other artworks in situ. This article will first introduce the sources for the 3D reconstruction and then investigate the role of ‘place’ in the evaluation of artworks in Pieter and Jacoba’s house. It will show how reconstructing the paintings’ context enriches our comprehension of the layered meanings that artworks hold in domestic settings.

The house and painting collection of Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker: sources for a reconstruction¶

The first source for the 3D reconstruction is the extant building on the Herengracht (no. 573) where Pieter and Jacoba lived together with their children for decades. Although both the interior and the façade have changed over the centuries, the building preserves the volumetric properties of the original seventeenth-century house and in part, as shown by architectural and archival research, the rooms within.[9] For this reason, the building serves as a reference point to spatialise the information contained in the rich archival documentation which consists of Pieter’s almanacs, his probate inventory, his and Jacoba’s testaments and a list of bequeathed goods. For more than forty years, Pieter, as VOC director in the Amsterdam chamber, noted his business and transactions on a yearly VOC almanac. These volumes contain plenty of information, also on the construction works on the Herengracht house, as he occasionally noted the names of artisans and artists who were working for him, the types and amounts of materials he ordered, and the furniture pieces or objects he commissioned.[10] Typical of ego-documents, these sources are patchy and often lack the necessary context for an external examiner to fully reveal the intricate meanings of these notes. Nevertheless, they offer a diachronic overview of the developments within the Herengracht house and of Pieter’s and his family’s life.[11]

By contrast, the detailed probate inventory that was drawn up on several occasions upon Pieter’s death offers a comprehensive snapshot of a specific time.[12] The inventory lists about a thousand objects divided by room and provided by an appraised value. We cross-referenced this list with the testaments of Pieter and Jacoba, which besides informing us about who inherited what, also gives us some spatial information about the layout of the house and the content of some of the rooms.[13] A complementary source of information is a document that lists all the objects coming from the Herengracht and Ilpenstein bequeathed to their eldest son Cornelis, which, with few exceptions, are not listed in the inventory.[14]

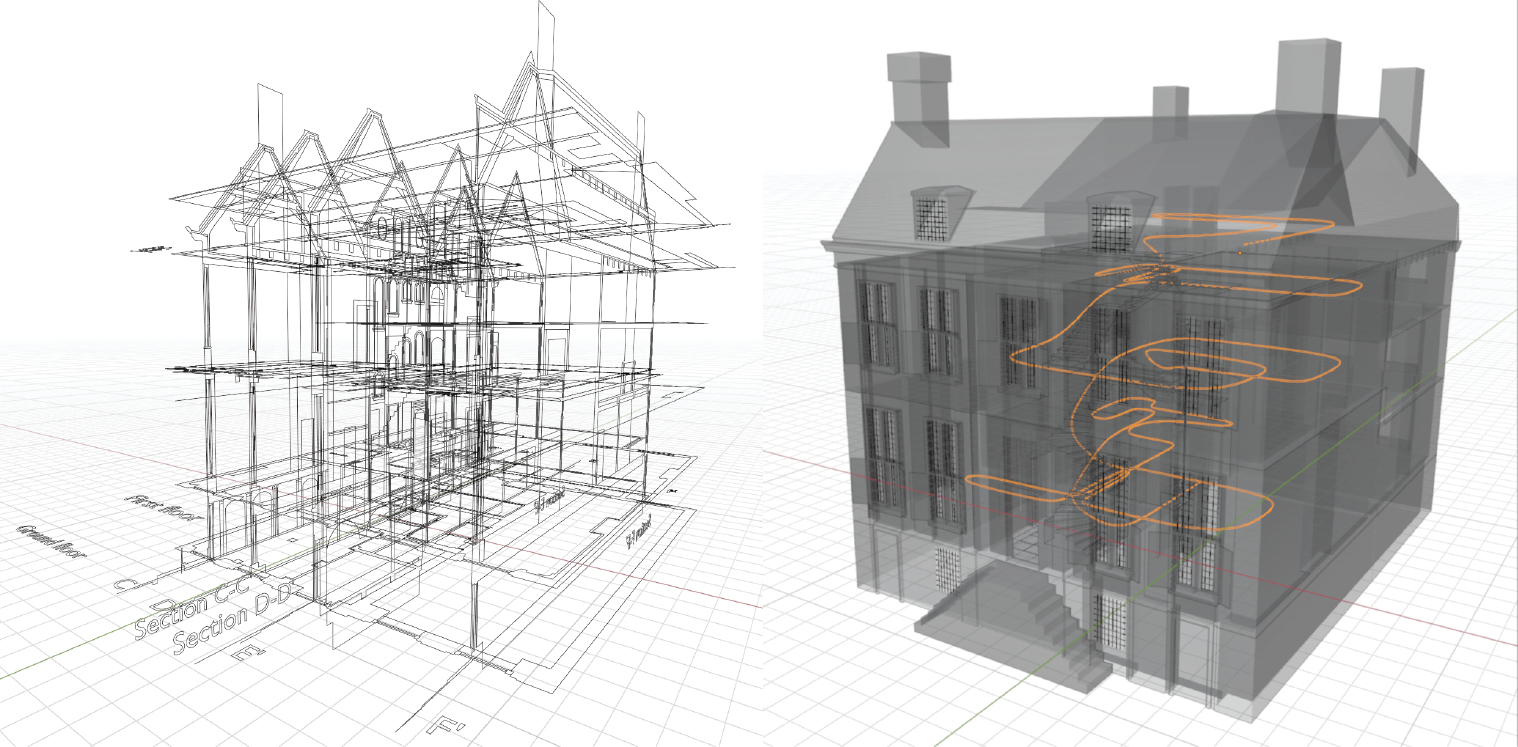

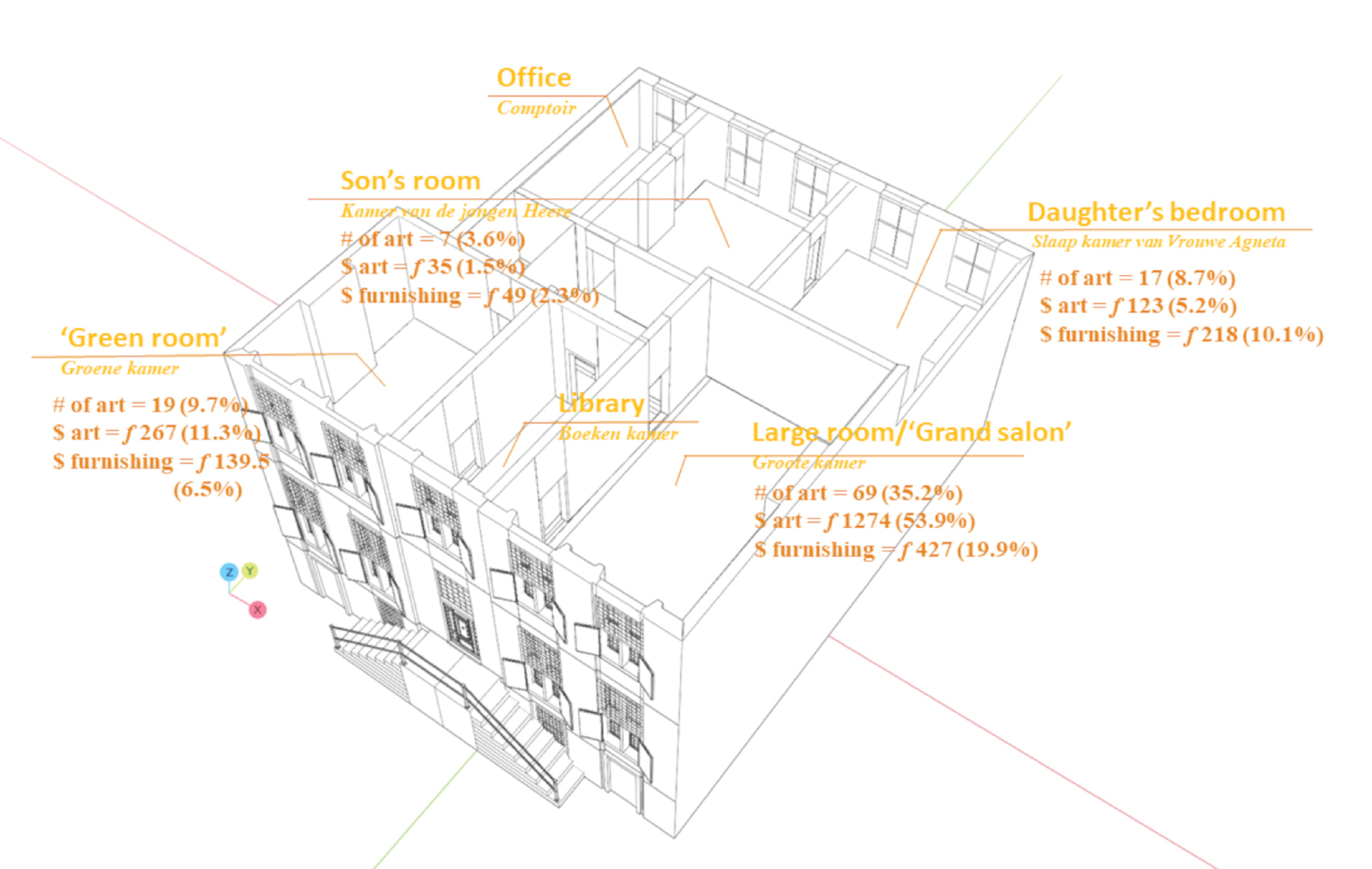

We compared the spatial information retrieved from the archival sources with the extant building and available building plans and sections to reconstruct both the route that the notary and his clerks took to make the inventory and the spatial arrangement of the seventeenth-century house in a 3D model (see Figure 1). A more detailed explanation of the creation of the 3D reconstruction is given in the methodological section. Developing this 3D reconstruction is crucial for facilitating and visualising our spatial analysis of the paintings within their original context, enabling us to map the rooms mentioned in the inventory onto a spatial framework.

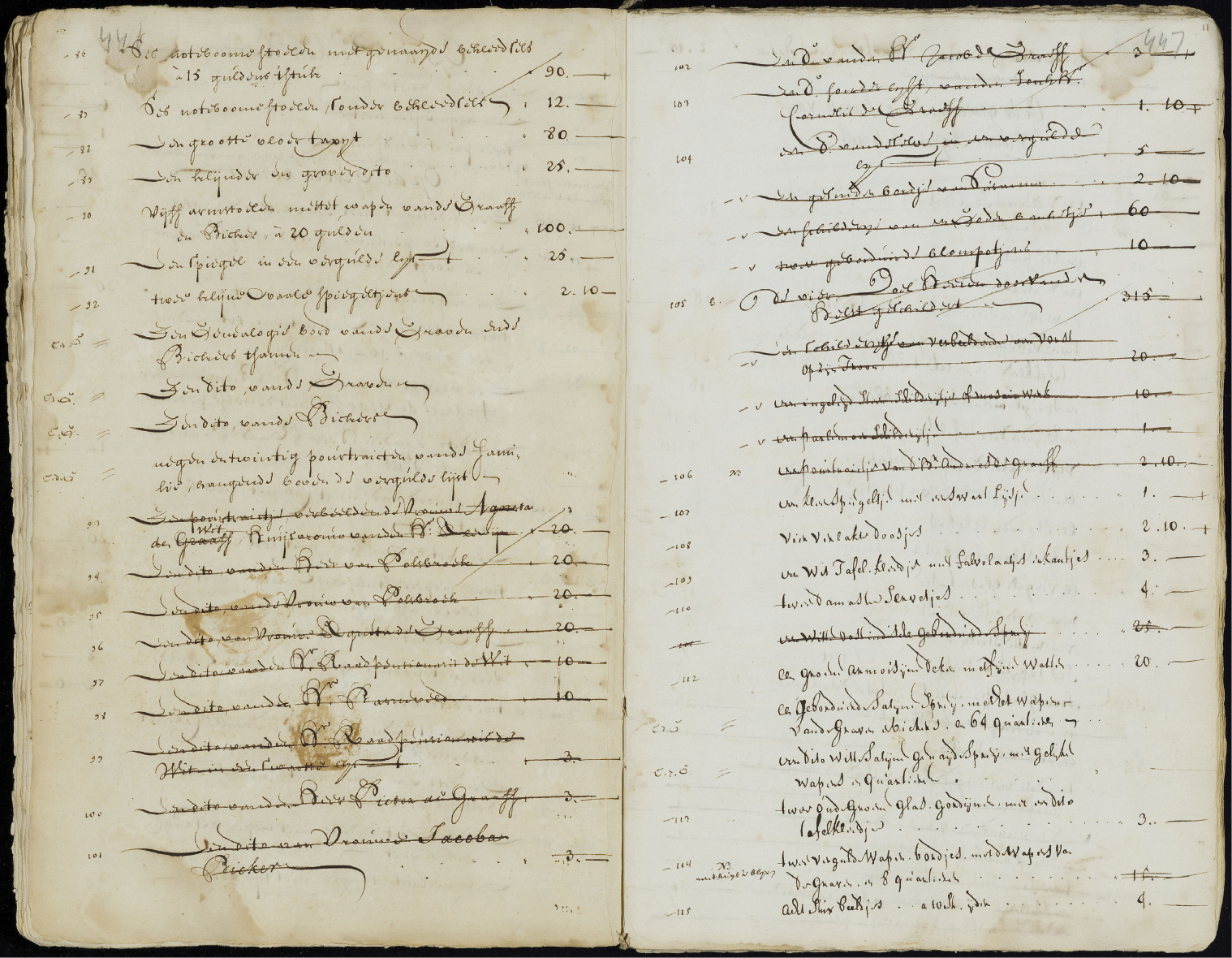

We now turn to the reconstruction of Pieter and Jacoba’s painting collection to discuss which sources we have at our disposal. Pieter’s inventory is a stratified source of high value for gaining knowledge of which paintings were recorded in the house after his death, and how they were appraised. A close examination of the inventory allows us to trace the sequence of paintings’ appraisals. A first list and taxation of paintings (we call it ‘List A’) were made in conjunction with the inventory of all the household objects (see Figure 2).[15] This list illustrates the paintings in context, given that they are recorded by room together with other objects. The paintings, however, needed to be investigated in more detail. Family portraits were bound by testamentary fideicommissum to remain within the family, some paintings were soon to be sold at an auction held by Pieter’s daughter Agneta, and others were already bequeathed to his son Cornelis. The notary and his clerks, moreover, seem to have been not particularly expert in appraising paintings and, as we gather from the paintings’ descriptions, looked mostly at the painting frames to gauge their value.

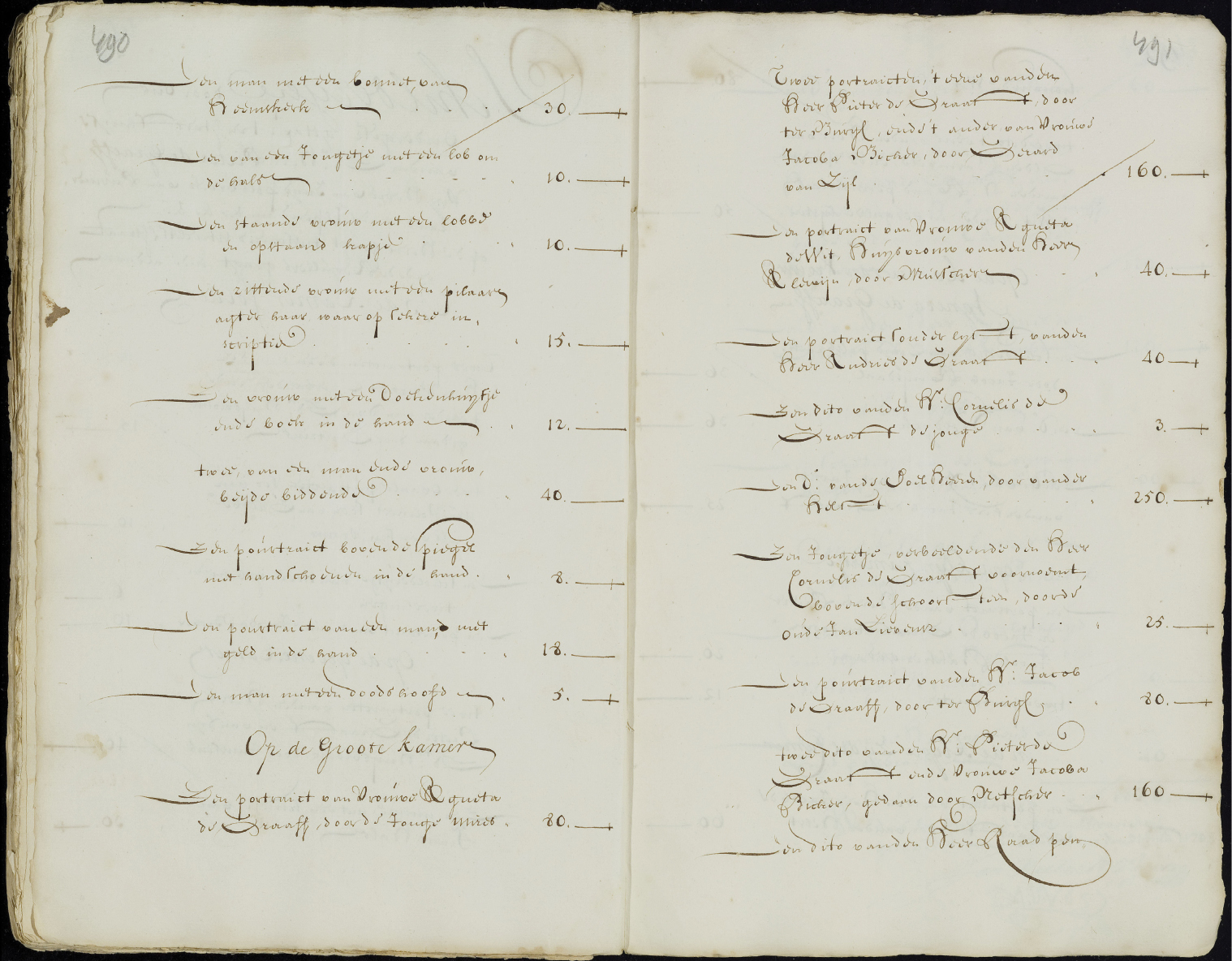

For this reason, the notary later asked art dealers Jan Pietersz Zomer and Anthony de Vos to make another, more detailed appraisal of paintings (‘List B’), distinguishing between paintings to be divided among the heirs and all the other paintings inventoried at the house on the Herengracht (see Figure 3).[16] Substituted by more accurate appraisals, the entries of paintings in List A were then crossed out. Since the updated List B also proceeds by room, by matching Lists A and B, we gain knowledge of the location of the paintings within the house and their correct and final estimated value. Among the notarial acts following List A was a list of around 90 paintings and other decorative pieces (drawings, watercolours, cameos, etc.) that Agneta intended to sell at a public auction on 7 July 1708.[17] Her paintings are mostly of mythological and religious subjects or still lifes. We identified the auction catalogue containing part of Agneta’s paintings as one of the anonymous catalogues in Gerard Hoet’s Catalogus (The Hague, 1752).[18] Thanks to this identification, we can name the makers of some of the paintings on the list.

The last source to reconstruct the painting collection is the list of household objects bequeathed to Cornelis, which informs us about the family portraits and other paintings that Cornelis received.[19] The paintings in both Agneta and Cornelis’s lists are not grouped by room, which prevents us from establishing their original location within the Herengracht house since they may have partly come from Ilpenstein castle in Ilpendam. We will come back to the portraits in Cornelis’s list in our analysis of the distribution of paintings per room to show how the 3D visualisation sheds light on their location. With all the available sources at hand, the following three sections will examine the role that the location of paintings played in the evaluation of artworks in Pieter and Jacoba’s house and explore the momentary, symbolic, and emotional values of this art collection throughout the house.

Placing values: the distribution of artworks by their monetary worth in the Herengracht house¶

The most straightforward way to understand Pieter and Jacoba’s choice of displaying art is to look at the spatial distribution of artworks by quantity and by monetary value. The couple kept around two hundred pieces of artwork in their Herengracht house, which were estimated at 2,363 guilders, on a par with the value of its furnishing (around 2,155 guilders).[20] Although a relatively large sum, this amount pales in comparison to the worth of gold/silverware and textiles in the inventory, which amounted to an astonishing number of over 5,000 and over 12,000 guilders, respectively.

How were these artworks displayed across different rooms in this imposing residence? The general impression of the painting distribution in seventeenth-century Dutch domestic interiors mainly comes from the widely cited study by John Michael Montias and John Loughman. In their Public and Private Spaces, the authors famously divide domestic interiors into public and private spaces to distinguish the varying social functions of these spaces. They observe a prevalence of more and higher-valued artworks in ‘public’ rooms – typically the most accessible rooms on the ground floor open to visitors – compared to fewer and less valuable pieces in the more secluded, family-oriented spaces at the back and upstairs, linking the display patterns of paintings to the accessibility and sociability of domestic spaces.[21] Subsequent research shows that early modern homes often had versatile, multipurpose spaces, thereby challenging the link between the painting display and the social function of the rooms. However, such multifunctional use of space is primarily observed in middle- to lower-class families with limited living areas.[22] The grand urban residences of patricians like Pieter de Graeff often provided ample space to assign specific social functions to different rooms.[23] The interplay between the spatial and functional arrangement and the painting display in the domestic interiors remains underexplored. Using the 3D layout of Pieter and Jacoba’s Herengracht house, this section explores the intricate interplay between art and space by examining how the couple distributed their paintings, measured by their monetary values, across different functional areas of their home.

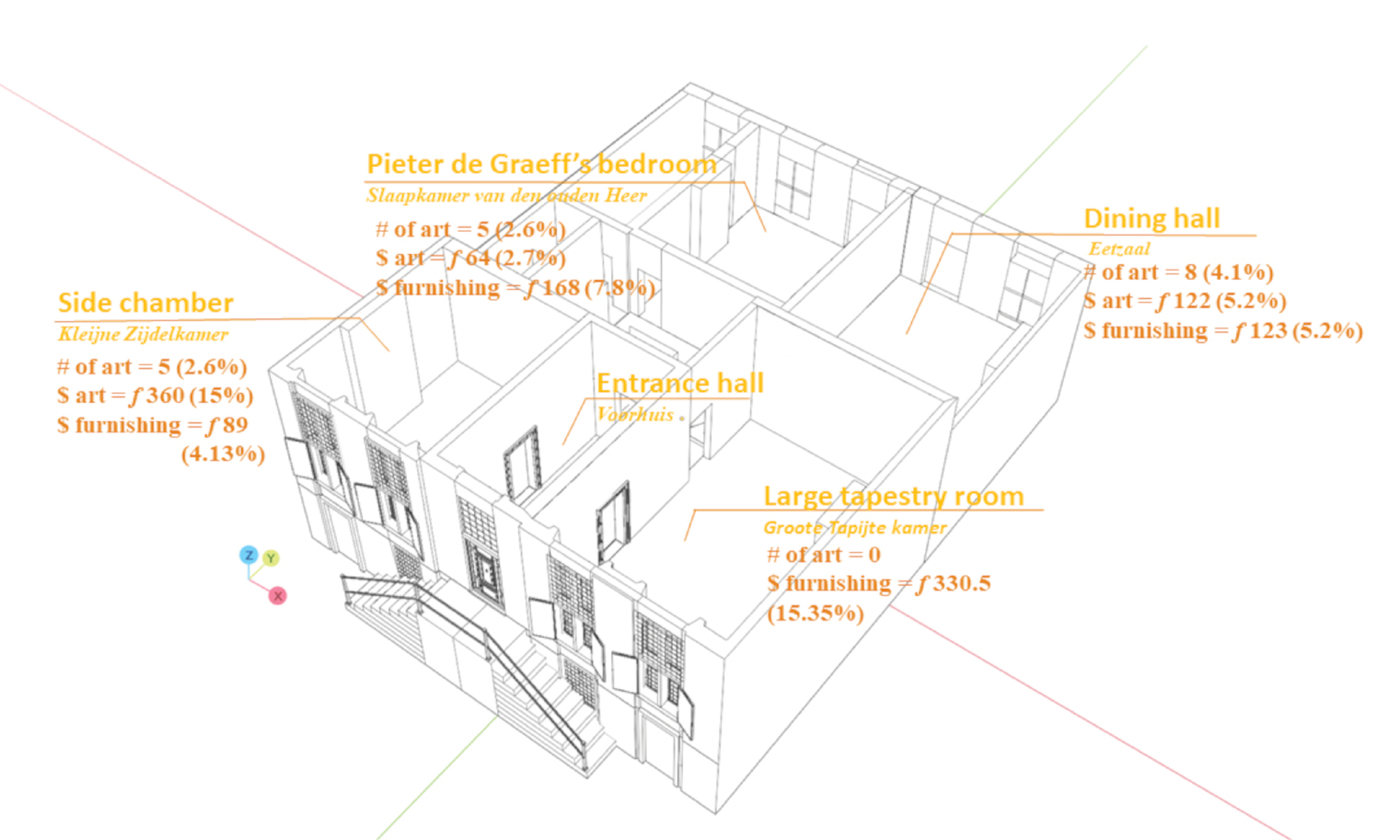

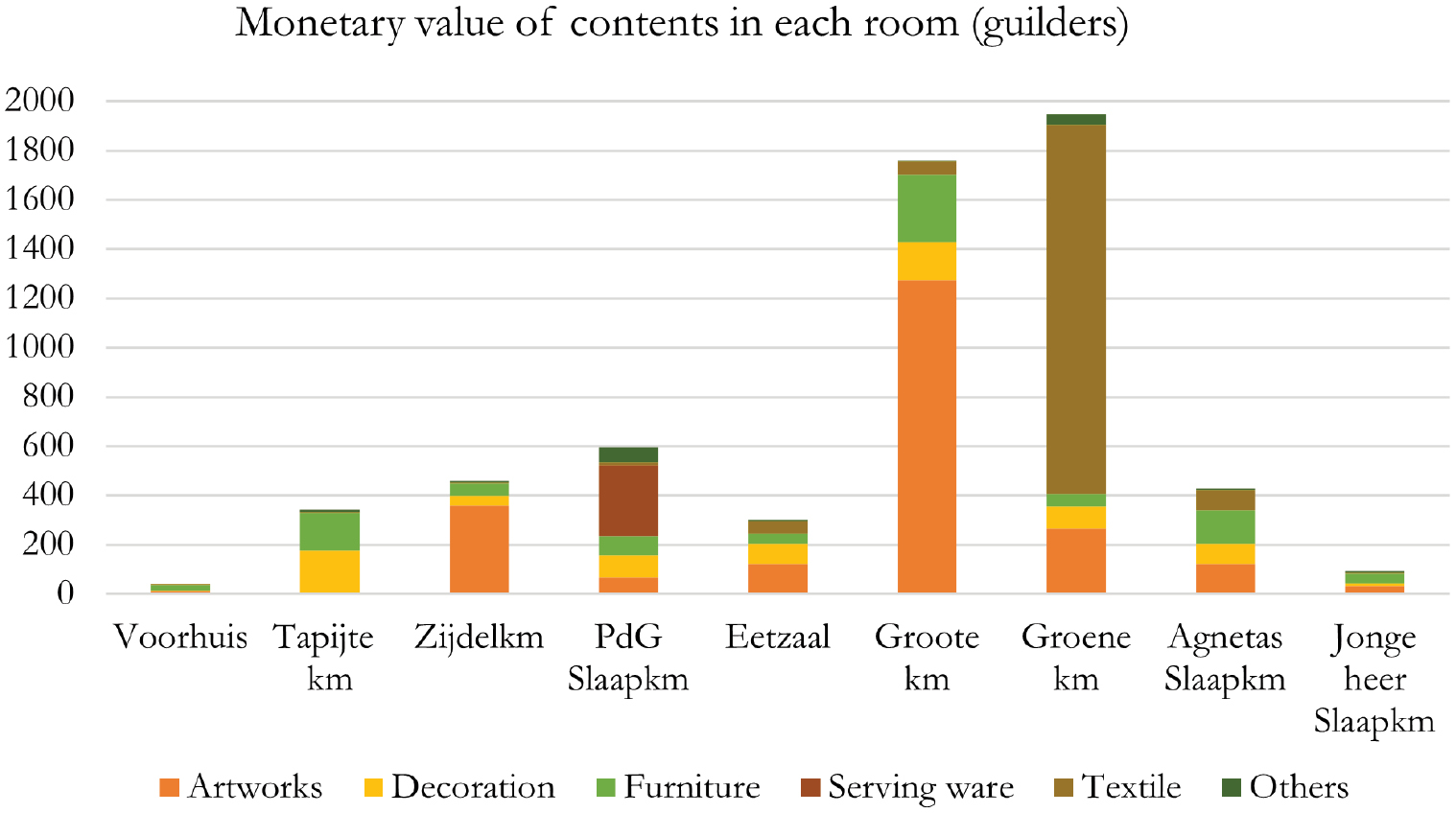

Figure 4 illustrates the three-dimensional layout of the ground floor of the Herengracht house. From the street, one enters the voorhuis (main entrance hall) through flights of two-way steps. The voorhuis was flanked by two parallel rooms, the groote tapijte kamer (‘large tapestry room’) and the kleijne zijdelkamer (‘small side chamber’). To their back lay the eetzaal (‘dining hall’) and the slaapkamer van den ouden Heer (‘bedroom of the old Lord’; Pieter’s bedroom). All rooms on the ground floor except for Pieter’s bedroom were accessible to visitors and served as public reception spaces. Following Montias and Loughman’s public and private dichotomy, therefore, they would have mounted more and higher-valued paintings. However, as Figure 4 shows, merely eight pieces of artwork were found in the so-called ‘public’ zijdelkamer, groote tapijte kamer, and eetzaal. These works of art amounted to 462.5 guilders, 19.6 per cent of the total appraised value of the art collection.[24] Figure 5 plots the monetary value of the objects inside all major spaces in this house. It shows that, although the kleijne zijdelkamer gathered a few valuable artworks (360 guilders) and the groote tapijte kamer had a relatively large share (15.4 per cent) of the furnishing in the house, they were far from the places that displayed a large number of high-value arts, which would have been expected according to Montias and Loughman.

Remarkably, it was in the upstairs spaces that we found the most imposing room measured by monetary worth (Figure 6). The groote kamer upstairs, which means ‘large room’ and is translated into ‘Grand Salon’ in some literature, housed over half of Pieter and Jacoba’s art collection, both by quantity and by monetary value as shown in Figure 3. The groote kamer was also the best-furnished room in the house.[25] The value of furniture and other decorations in this room (427 guilders) even exceeded that of the groote tapijte kamer downstairs (330.5 guilders). Pieter also kept his large collection of commemorative medals and coins in the groote kamer which he amassed over the years and stored in the luxurious cabinets in this room.[26] Although it is often assumed by researchers that rooms like these were located on the ground floor, our spatial reading of around three hundred inventories in Amsterdam suggests that it was not always the case, as several households in our sample placed the best-bedecked room on the street-facing side of the first floor, just like Pieter and Jacoba did with the groote kamer.[27]

This observation indicates that the relative position of a room within the interior, particularly its accessibility, might not necessarily determine its function or influence the choice for displaying paintings. When less accessible rooms assumed social function, the visitors’ experience of the interior space would have been different than what Montias and Loughman described. Likewise, the contents in the groene kamer (‘green room’) and the boeken kamer (library) next to the groote kamer on the same floor also blur the distinctions between social functions typically associated with public and private spheres. In his almanacs, Pieter mentioned the visit of a family friend to the library upstairs to browse through his book collection and borrow a few pamphlets.[28] Therefore, by linking the monetary value of artworks with the spatial configuration of the house, we can deduce the intended function of different spaces and envisage the experience of moving through connecting spaces. Such an aggregated approach, albeit useful, still lacks object-oriented details. It is necessary to go beyond abstract statistics and look at individual items and their locations to grasp the symbolic value of artworks in situ.

Displaying status: Symbolic value of paintings and interior decoration¶

When looking closely at the objects present in each room, we see a more nuanced and sophisticated value distribution, such as the symbolic and emotional values which could not be fully captured or presented by the appraised monetary sum. To fully understand the use of interior space in this house, this section examines the display of artworks and other decorations as status symbols and analyses the practice of symbolic display at home among the upper echelon of Amsterdam society.

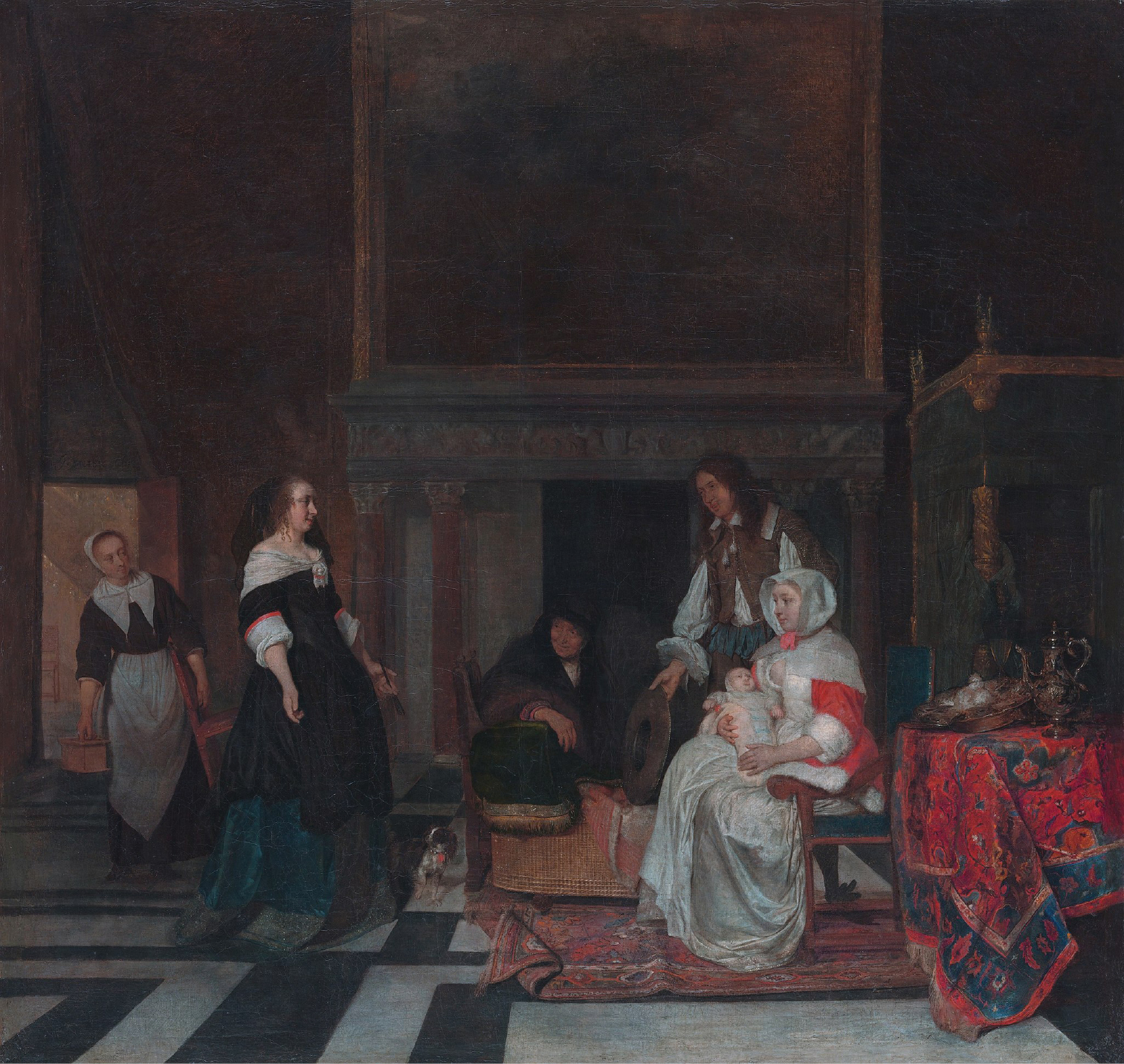

The most ostentatious display of Pieter and Jacoba’s status as patrician elite was the decoration of the groote tapijte kamer. As its name suggests, this capacious room – measuring 9.4 by 5.8 metres – was lavishly decorated with tapestry wall hangings and luxurious Turkish floor carpet.[29] Next to the tapestries, this room was sparsely furnished with a marble table, a painted tea table, and fifteen chairs. No paintings or other works of art were listed in the inventory, but there was likely an overmantel piece fixed to the wall (‘spijkervast’) like in Gabriël Metsu’s The Visit to the Nursery (Figure 7), which was not mentioned in the movable estate.[30] Next to the tapestry wall hangings, only two mirrors adorned the walls presumably between the windows.[31] This tapestry bedecked, sparsely furnished room often served as a status symbol among the urban elites during the last decades of the seventeenth century.[32] Although the concept of ‘aristocratisation’ is challenged by several scholars, it is generally agreed that, in the second half of the seventeenth century, the urban patrician class began to seek status symbols in their cultural consumption and adopted aesthetics that were previously associated with nobilities.[33] For instance, they promoted costly textiles like tapestries as popular wall coverings, which were almost exclusively seen in the houses of nobilities before the late seventeenth century.[34]

These tapestry wall hangings were often more valuable than easel paintings and were therefore considered a showpiece. The wall-hanging tapestries in Pieter and Jacoba’s house were alas not appraised, but similar tapestries in other houses of Amsterdam elites were valued from around 1000 to over 3000 guilders.[35] In addition to the presence of tapestry wall hangings, the subject matter for the tapestries also reveals the couple’s intention to accentuate or even elevate their social status. According to the inventory, the tapestries depicted the ‘deeds of Alexander [the Great]’ (‘de daden van Alexander’), a subject matter that situated the owner among the nobilities, implying the wealth, power, and virtue of the family.[36] Even without knowing the exact monetary worth of these wall hangings, these tapestries depicting the courageous king offered much symbolic value for an ‘aristocratic’ display of status. Although no portrait or coat of arms of De Graeff’s or Bicker’s families was found in this room, their status and intention were unmistakably conveyed through such an ostentatious presentation of tapestry wall hangings depicting the powerful figures in history.

In contrast to the groote tapijte kamer, which presented no direct family symbol, the kleijne zijdelkamer across the voorhuis offered a downright power display. This room mounted only five paintings, all portraits of the highly selected and most illustrious figures of the De Graeff and the Bicker families who once held high positions in Amsterdam’s political scene, such as Pieter’s uncle Andries (1611-1678), his grandfather Jacob Dircksz (1571-1638) and his father-in-law Jan Bicker (1591-1653), next to the portraits of Pieter himself and his brother Jacob (1642-1690).[37] All five portraits were appraised with high value and made by most sought-after portraitists like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613-1670), and Thomas de Keyser (ca. 1596-1667) but art historians have not been able to trace down the exact paintings matching the attributions.[38]

Given the active years of these famous painters, the portraits hung in the kleijne zijdelkamer were all made before or around the time the couple moved into this house in 1666 and therefore might have been on display for over four decades. Soon after moving into the Herengracht house, however, the De Graeff’s were removed from the Amsterdam City Council in 1672, due to their political alliance and kinship with the Grand Pensionary of Holland, Johan de Witt. The De Graeff family never regained their political power in the city, although Pieter withheld his position as VOC director until his death. However, by displaying these powerful family members in this accessible and business-oriented side chamber, Pieter and Jacoba reminded the visitors of their patrician status. This placement of the excellently executed portraits of the important figures in the family certainly boosted the symbolic value of the artworks beyond their monetary worth.

Providing the context for the family portraits on the walls of the kleijne zijdelkamer was the ceiling painting, commissioned to Paulus de Fouchier around 1682 to 1685, a decade after the Rampjaar (see Figure 8). The centrepiece of Fouchier’s ceiling work depicts the maid of Amsterdam surrounded by the personifications of the four continents, stressing the far-reaching impact of Amsterdam’s trading network, in which the De Graeff’s and the Bicker’s played an important role. The mediocre execution of Fouchier’s ceiling pieces did not seem to have bothered Pieter and Jacoba, even though they must have been familiar with the masterpieces of a similar size by the great Dutch Classicist painter Gerard de Lairesse in the nearby house of Pieter’s uncle Andries de Graeff (Herengracht 446) since 1672.[39] Despite having been exposed to high-quality paintings in their circle, the choice still fell on a mediocre painter to produce the ceiling pieces as part of their power display. It seems that the subject matter, which highlighted the dominance of Amsterdam and its commercial supremacy, mattered more than the artistic quality of the execution. The symbolic value of these paintings trumped the aesthetic or perhaps the monetary value in the display of status in this room. These ceiling paintings, together with the power display through exhibiting selected, high-quality portraits made the kleijne zijdelkamer exude a sense of potency and formality.

In addition to the aristocratic and power display in the ground floor rooms, the groote kamer upstairs offered an intimate yet imposing showroom for the De Graeff’s and Bicker’s family history and wealth, overshadowing the aforementioned rooms downstairs in terms of the richness, diversity, and value of its artworks and furnishing. Unlike the two sparsely furnished rooms downstairs, the groote kamer was filled with expensive furniture. This seemingly large space, measuring around 9 by 6 meters, contained no fewer than seven cabinets made of expensive materials next to a hefty bedstead and a bulky cupboard, all of which were not found in the ground floor rooms.[40] In addition to these large pieces of furniture, there were also seventeen chairs, divided into three levels of embellishments. The most expensive ones are the five armchairs with the coats of arms of both the De Graeff and the Bicker families, celebrating the union of these two influential families in Amsterdam.

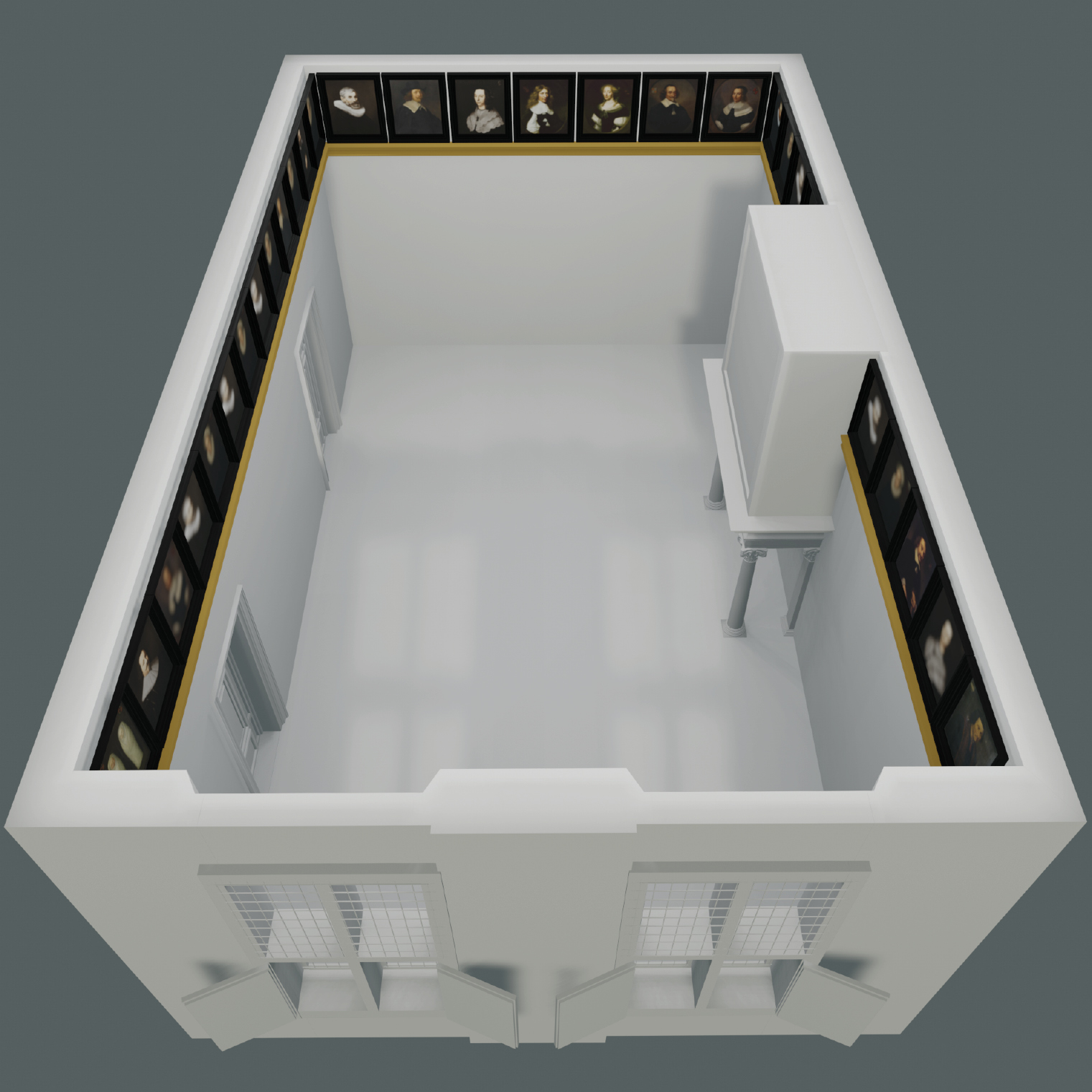

With these many pieces of furniture taking up the wall spaces, it is hard to imagine how Pieter and Jacoba managed to display around fifty paintings – mostly ancestral portraits and coats of arms – in the same room.[41] Fortunately, the inventory left some indications of how the paintings were exhibited. As in the case of the entry in the list of objects bequeathed to Cornelis, the notary or his clerk noted ‘twenty-nine portraits of the family, hanging above the gilded frame’ (‘Negen en twintig pourtraicten van de familie, hangende boven de vergulde lijst’).[42] This ‘gilded frame’ likely referred to the wood or plaster moulding that appears in several architectural paintings of the early seventeenth century, such as Frans Francken’s interior piece (Figure 9) depicting the house of the Antwerp patrician and nine-time burgomaster Nicolas Rockox (1560-1640), a man of the similar stature as Pieter de Graeff.[43] Although the setting in Francken’s painting might have been partially fictional following the pictorial tradition of the ‘constcamer’ (art room or curiosity cabinet), the moulding in this room that separated two decoration planes on the wall offers a visual reference for the ‘gilded frame’ in the groote kamer.[44] Like the landscapes above the wooden moulding in Rockox’s reception room (Figure 9), the couple might have lined the ‘twenty-nine family portraits above the gilded frame’ next to each other along the upper segment of the walls in the groote kamer. Substantiating our hypothesis, we found a series of bust-sized portraits of the couple and their extended families from the late sixteenth century to the early eighteenth century (such as Figures 10 to 13).[45]

Despite their wide time range, all of these portraits measured around 70 by 60 centimetres and all of the sitters in these portraits were similarly posed and dressed in sober colours, presumably to fit into the same series. The pendant portraits of Pieter and Jacoba (Figures 10 and 11) were likely made for this purpose as both assumed formal poses and were dressed in black and white. Although the couple was dressed according to the latest fashion in costume, the sober colours had become outmoded and were often replaced by brighter colours in portraits by popular painters like Nicolaes Maes.[46] Moreover, some of these bust-size portraits were copied after other large, even life-size portraits, suggesting that commissioning and displaying a series of family members in the collection of the patrician class was a common practice throughout the seventeenth century.[47] However, it remains unclear how the series of family portraits could have been exhibited at home and whether they would have fit side by side on the groote kamer’s walls. The 3D reconstructions of the Herengracht house offer an excellent opportunity to experiment with the display patterns of the portraits.

Taking the 70 by 60 centimetres as the recurrent size and adding a frame around each of the portraits, a series of portraits has been modelled as well as a gilded moulding running along the groote kamer’s walls. The portraits that we have identified as possibly part of this ‘gallery of ancestors’ have been included in the 3D reconstruction, while for the others a blurred painting has been used as a placeholder. This 3D reconstruction shows that 29 portraits could have been perfectly lined up on the upper part of the walls (Figure 14). Such tight disposition finds precedence in paintings, such as Jan Miense Molenaer’s Family Making Music, where a few portraits in black frames are arranged one right after the other above a moulding running along the wall behind the main figures (Figure 15). Contrary to the portraits in Molenaer’s painting, however, the portraits in the groote kamer must have been placed on the upper part of the wall and not at eye level, as the door openings would have reduced the surface available to fit all portraits. This 3D reconstruction also allows us to experiment with different types of frames to see the different effects.

Below the gallery of the ancestor portraits, the inventory shows that the lower section of the groote kamer displayed portraits of Pieter de Graeff’s immediate family. The well-known portraits of the couple by Casper Netscher and of Pieter’s brother Jacob de Graeff by Gerard ter Borch (all in the Rijksmuseum) were found in this room. Although made by different painters ten years apart, these portraits had the exact size and shape. Pieter had expressively bought two oval-topped wooden panels on which Ter Borch would paint two identical portraits of Jacob.[48] The occasion to immortalise was important: in July 1673, at the same time in which the portraits were commissioned, Jacob had voluntarily joined the army of Stadholder Willem III against the French, and it is indeed in a military dress that he is portrayed in the painting.[49]

Next to the portraits of Pieter de Graeff’s next of kin, there were two portraits of Johan de Witt, together with a portrait of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt in the same room.[50] Exhibiting portraits of controversial political figures in the imposing groote kamer points to the symbolic use of such portraits to demonstrate political alliances. Considering these symbolic statements made by lavish furnishing, ancestral portraits, and political association, it is hard to imagine that this groote kamer was a private space, exclusively reserved for family members. It seems that the semi-public space upstairs was equally, if not more, important for the symbolic display because it was open to members in their social circles where real relationships were built and maintained.

A personal touch: Emotional value of paintings in private bedrooms¶

Besides the symbolic value of artworks in Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker’s residence, there are traces of the emotional value that paintings provided for the family. Even in the most imposing groote kamer, where a series of ancestral portraits and family trees were displayed, De Graeff commissioned and installed a painting of his eldest son Cornelis as an overmantel piece when Cornelis was just beyond infancy.[51] In a letter to Johan de Witt, Pieter mentioned the commissioning of this piece, saying that the top-tier painter Jan Lievens (1606-1674) was going to paint his son ‘as naked as a cupid’.[52] However, the exact painting by Lievens has not yet been identified. Despite lacking the visual reference, showing such an intimate portrait of his son in the groote kamer might have offered more emotional comfort than the commissioned and appraised worth could express.

The emotional values of paintings transpire even more in the private bedrooms of the family. Considering the content and position of Pieter’s bedroom in the inventory as well as its location when plotting the rooms in the 3D reconstruction, we can conclude that it was moved down to the ground floor in the room below the comptoir, at the back of the house facing the garden. In fact, in the testament Pieter and Jacoba made in 1695 (just a few months before Jacoba’s passing) they refer to the comptoir as ‘the room being above our current bedroom’.[53] As is clear from archival sources and Pieter’s own almanacs, health-related issues vexed the couple in the last decades of their lives.[54] This change must have been dictated by the necessity to ensure they could move more easily and safely within and outside the house. In this bedroom, the inventory records only two easel paintings and two drawings, in addition to luxurious wall coverings and other furnishings.[55] The four paintings and drawings all depicted Pieter’s country properties, Ilpendam and Polsbroek, from which, as already mentioned, he held his lordly titles.[56] One of the easel paintings was said to be made by landscape painter Isaac de Moucheron (1677-1744), who did not return to Amsterdam until 1697.[57] It means that Pieter must have commissioned the work in his last years and clung to his lordly titles and lordship by the end of his life. These representations of his country properties had comforted him beyond any simple landscape could offer.

Pieter de Graeff was not the only resident in the house. His daughter Agneta married at the age of 40 in 1703, and up until that time was living in this house together with her father. The artworks in Agneta’s bedroom were the most diverse compared to all other rooms in this house. Several paintings depicted mythological and religious scenes with female subjects. Stories of love and seduction, such as ‘Venus and Adonis’, ‘Vertumnus and Pomona’, and the ‘bathing Diana’ were placed alongside scenes of devotion and piety such as Maria’s annunciation and contemplation, accompanying Agneta in her private space.[58] Once again, the emotional value of paintings trumped their attribution and monetary worth.

Conclusion¶

In this article, we have analysed the monetary, symbolic, and emotional values of artworks in the house of Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker at Herengracht 573. The 3D reconstruction of the house helped us visualise and analyse the domestic space and the art collection in its original context. Such spatial 3D mapping has allowed us to reconstruct the rooms’ positions and volumes which has in turn enabled us to quantify and compare the amount and distribution of paintings across the various rooms. Our study shows the importance of place in the identification, perception, and interpretation of works of art. It illustrates how the interior space and its furnishing influence our understanding of the motivation and behaviour of the owners to appreciate paintings in their original setting. Our analysis suggests that even rooms that traditionally have been considered private quarters (such as the groote kamer on the upper floor) contained in fact typical features of spaces serving more public functions, with a keen attention to the display of status, lineage, and wealth. This study provides insights into the dynamics of self-representation of the Amsterdam elite in the seventeenth century where their house functioned as a projection of self and an expression of identity.

The preserved archival materials allowed us to gain a holistic view of the art collection on display in this house and identify the placement of paintings in each room. Moreover, the research on the archival sources about this family helped us associate the house and the paintings on display with the persons who gathered, exhibited, and experienced this art collection. For example, the knowledge of Pieter’s and Jacoba’s deteriorating health leading to the necessity to move to the room downstairs, or Agneta living with her father until her late marriage nuanced our understanding of the choices made about the type of paintings that they wanted to be surrounded with in their private spaces.

The challenges of this type of research relate to dealing with possibly incomplete data and reintroducing a spatial dimension into textual archival documents. Questions always remain open when analysing inventories regarding household properties that for various reasons (fixed furniture or decorations, or already bequeathed) were not recorded in inventories. In our case, complementary archival records, such as the list of objects bequeathed to Cornelis and Pieter’s almanacs, filled in or hinted at some of the missing information. Our findings regarding the symbolic and emotional values of the paintings on display are therefore not affected by the potential presence of some more paintings.

As demonstrated in this article, the proposed approach which relies on a 3D reconstruction of the house to map and visualise paintings is well suited for statistical and distribution analysis across and within rooms. However, as discussed in the methodological section, it must be noted that reconstructing the disposition of paintings on the wall with a higher level of detail is complex and would only be possible if the dimensions of the paintings are known. Our visualisation of the portrait series lined up in a gallery of ancestors on the upper walls of the groote kamer was made possible only after we recognised a pattern in the measurements of the known family portraits while knowing the dimensions of the room. Proposing a more detailed reconstruction of the disposition of the paintings in the lower part of the walls remains challenging because the wall spaces were occupied by not only paintings but also furniture and other decorative arts. Despite varying degrees of applicability based on various cases, 3D modelling opens new avenues for (art) historians to investigate the interior space and material culture of the past.

Footnotes¶

[1] This research took place in the context of the Virtual Interiors project (https://www.virtualinteriorsproject.nl/).

[2] Cf. Krista Kodres and Anu Mänd, Images and Objects in Ritual Practices in Medieval and Early Modern Northern and Central Europe (Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2014); Ronni Baer (ed.), Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer, First edition (MFA Publications 2015); Grażyna Jurkowlaniec, Ika Matyjaszkiewicz and Zuzanna Sarnecka (eds.), The Agency of Things in Medieval and Early Modern Art: Materials, Power and Manipulation (Taylor & Francis 2017). DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315166940; Abigail Brundin, Deborah Howard and Mary Laven, The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy (Oxford University Press 2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198816553.001.0001; Maria F. Maurer, Gender, Space and Experience at the Renaissance Court: Performance and Practice at the Palazzo Te (Amsterdam University Press 2019). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048536689; Susanna Burghartz a.o. (eds.), Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450-1750: Objects, Affects, Effects, Visual and Material Culture, 1300-1700/Series Editor: Allison Levy, 28 (Amsterdam University Press 2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1w9m9f9.

[3] Cf. Maurer, Gender, Space and Experience; Saskia Beranek, ‘Strategies of Display in the Galleries of Amalia van Solms’, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 9:2 (2017). DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2017.9.2.4; Sandra Cavallo, Domestic Institutional Interiors in Early Modern Europe (Routledge 2017); Gail Feigenbaum (ed.), Display of Art in the Roman Palace, 1550-1750 (Getty Research Institute 2014).

[4] Eric Jan Sluijter, ‘All Striving to Adorne Their Houses with Costly Peeces’: Two Case Studies of Paintings in Wealthy Interiors’, in: Mariet Westermann (ed.), Art and Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt (Waanders 2001); H. Perry Chapman, Frits Scholten and Joanna Woodall (eds.), Arts of Display/Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, 1565 (Brill 2015).

[5] Mary C. Beaudry, ‘Households beyond the House. On the Archaeology of Materiality of Historical Households’, in: Kevin R. Fogle, James A. Nyman and Mary C. Beaudry (eds.), Beyond the Walls: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Historical Households (University Press of Florida 2015) 1-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvx074hg.6.

[6] The letters are kept in the Nationaal Archief (National Archives) in the Hague, inv. nr. 3.01.17.

[7] On elite culture, see Luuc Kooijmans, ‘Patriciaat en aristocratisering in Holland tijdens de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw’, in: Johan Aelbers and Maarten Prak (eds.), De bloem der natie. Adel en patriciaat in de Noordelijke Nederlanden (Boom 1987) 259-306; Luuc Kooijmans, Vriendschap en de kunst van het overleven in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw (Bert Bakker 1997).

[8] For the discussion of the relocation of the patrician class, see Weixuan Li, Painters’ playbooks: Deep mapping socio-spatial strategies in the art market of seventeenth-century Amsterdam (PhD Diss., University of Amsterdam 2023).

[9] On this, see the methodological section in the HTML-version of this article, and Chiara Piccoli, ‘Home-making in 17th century Amsterdam: Investigating visual cues in domestic interiors by means of a 3D digital environment’, in: Giacomo Landeschi and Eleanor Betts (eds.), Capturing the Senses: Digital Methods for Sensory Archaeologies, Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences (Springer 2023) 211-236. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23133-9_10; Chiara Piccoli, Pieter de Graeff (1638-1707) and his treffelyke bibliotheek: Exploring and reconstructing an early modern private library as a book collection and as a physical space (Brill forthcoming); and Chiara Piccoli ‘A peek behind the façade: The Virtual Interiors approach to visualise Herengracht 573 in the XVII century’, Storia Urbana (Mapping Early Modern European Cities. Digital Projects of Public History) 173 (2022 [2024]) 79-98. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3280/SU2022-173006.

[10] Stadsarchief Amsterdam (henceforth SAA), 76 Archief van de familie De Graeff, inv. nrs. 186-226 (1664-1707).

[11] See Piccoli, Pieter de Graeff.

[12] SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam (henceforth SAANA) (nr. 5075), inv. nr. 5001, pp. 425-493, notary Michiel Servaas (nr. 199), 8 March 1709. For the transcription of pp. 425-477 see DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7501160.

[13] Testaments made on 28 May 1688 (not. Godefridus Bullik) and on 31 January 1695 (not. Gerrit Steeman) (SAA 76, inv. nr. 609, Portefeuille 2).

[14] SAA 76, inv. nr. 606A, series nr. A 90, unpaginated.

[15] SAA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 425-477.

[16] SAA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 489-493.

[17] SAA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 477-481.

[18] In Gerard Hoet, Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen, met derzelver pryzen zedert een langen reeks van Jaaren zoo in Holland als op andere Plaatzen in het openbaar verkogt, vol. 1 (The Hague 1752) 123-4.

[19] SAA 76, inv. nr. 606A Serie A90, unpaginated.

[20] The actual value should be higher since not all art pieces were appraised as discussed earlier.

[21] John Loughman and John Michael Montias, Public and Private Spaces: Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses (Waanders 2000) 59-69.

[22] Paula Hohti Erichsen, Artisans, Objects and Everyday Life in Renaissance Italy the Material Culture of the Middling Class, Visual and Material Culture, 1300-1700 (Amsterdam University Press 2020) 228. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048550265.

[23] Cf. Stacey Sloboda, Interiors in the Age of Enlightenment: A Cultural History (Bloomsbury Publishing 2023). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350408036.

[24] As for the voorhuis, the inventory did not register the ten grisailles (four larger ones with allegorical subjects and six smaller ones), which were described in Pieter’s almanacs. See Piccoli, ‘Home-making’.

[25] The actual value of the content in the groote kamer could have been even higher because several paintings and pieces of furniture were already bequeathed to the heirs and were not appraised. See SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 445.

[26] SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 445: e.g. ‘Twee noteboome cabinetjens tot medailles yder f 10, tsamen’; ‘Een Oost Indisch verlakt medaille cabinet met desselfs vergulde voet’.

[27] Li, Painters’ Playbooks.

[28] SAA 76, inv. nr. 196 (1676), 17 November.

[29] Unfortunately, the tapestry wall hangings were not appraised. However, the Turkish floor carpet, by itself, was valued at 100 guilders, giving out an impression of opulence of this room.

[30] The inventory of the groote tapijte kamer suggests that Metsu’s The visit to the nursery was largely true to reality for several key furnishing items were also registered in the inventory. In addition, Pieter de Graeff mentioned in his almanacs that his sister-in-law gave birth in the groote tapijte kamer in 1673. For the description of this event, see SAA 76, inv. nr. 193 (1673), 16 May.

[31] The two mirrors were registered right before two pieces of window curtains (glasgordijnen), suggesting that they were hung between the windows.

[32] This preference for tapestries is often considered as part of the social process of ‘aristocratisation’ (veradelijking), which is well discussed in Kooijmans, ‘Patriciaat en aristocratisering’ 259-306. The ‘aristocratisation’ of elites in the late seventeenth century has been used by art historians to explain the refinement in painting styles and the choice of subject matters, see Ekkehard Mai, Sander Paarlberg and Gregor J.M. Weber, De kroon op het werk: Hollandse schilderkunst 1670-1750 (Verlag Locher 2006).

[33] See the many articles published in Virtus | Journal of Nobility Studies, especially those by Yme Kuiper and Rob van der Laarse. For the most recent discussion see Rob van der Laarse, ‘Burgers op het kasteel. Elitedistinctie en representatie onder Hollandse heren buiten de ridderstand in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw’, Virtus | Journal of Nobility Studies 29 (2022) 34-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21827/virtus.29.34-64.

[34] The tradition of hanging wall tapestries among the nobilities is summarised in Eric Jan Sluijter, ‘Ownership of Paintings in the Dutch Golden Age’, in: Ronni Baer (ed.), Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer (MFA Publications 2015) 90-92; Cornelia Willemijn Fock (ed.), Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld 1600-1900 (WBooks 2001) 101.

[35] The purchase price of the tapestries could be suggested by the case of Amsterdam burgomaster Joan Huydecoper in the 1640s. He spent 3,280 guilders for the tapestry and the overmantel by Joachim von Sandrart. Ottenheym indicates the tapestry cost 3,000 guilders. Sluijter, ‘Ownership of Paintings’, 287, note 12; Koen Ottenheym, Philips Vingboons (1607-1678), architect (Walburg Pers 1989) 247, note 97. In the zijkamer of the famous Bartolotti house, the hanging tapestries were assessed at 900 guilders. A similar tapestry room appeared in the house of David van Baerler (1671). The full inventory drawn from the Bartolotti house, see Gustav Maria Leonhardt, Het huis Bartolotti en zijn bewoners (Meulenhoff 1979).

[36] The same subject matter appeared in the inventory of the Stadhouder Quarter and the House in the Noordeinde (Oude Hof) in 1632. See Sophie W.A. Drossaers and Theodoor H.L. Scheurleur, Inventarissen van de inboedels in de verblijven van de Oranjes en daarmede gelijk te stellen stukken, 1567-1795, vol. 1 (Nijhoff 1974) 196. For the discussion of the fashion of tapestry wall hangings, see Fock, Het Nederlandse interieur, 101.

[37] Pieter’s father, the famous burgomaster Cornelis de Graeff, is absent from this list, which is hard to explain given their close relationship (Pieter speaks fondly of him in the manuscript book he wrote about his family, SAA 76, inv. nr. 227) and the importance of his father who would have fit very well this display of eminent family members. It is possible that Cornelis’ portrait was already bequeathed to somebody else and hence excluded from the inventory, or he might be featured in the overmantel piece which was not appraised.

[38] See SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 486. For the transcription, see Getty Provenance Inventory N-470.

[39] For the paintings, see Gerard de Lairesse, Allegory of Trade, 1672, oil on canvas, 446 × 202 cm, 446 × 232 cm, and 446 × 185 cm. The Hague, Vredespaleis.

[40] The furniture was registered in SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 445-446.

[41] The inventory registered forty-nine paintings (forty-three out of which were portraits), three genealogy boards, two boards of coat of arms. SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 447.

[42] Cited from SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 446.

[43] Lisa Rosenthal, ‘Art Lovers, Pictura, and Masculine Virtue in the Konstkamer’, in: Dawn Odell and Jessica Buskirk (eds.), Midwestern Arcadia: Essays in Honor of Alison Kettering (Northfield 2014) 100-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18277/makf.2015.09; Sven Dupré, ‘Trading Luxury Glass, Picturing Collections and Consuming Objects of Knowledge in Early Seventeenth-Century Antwerp’, Intellectual History Review 20:1 (2010) 53-78. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17496971003638258.

[44] For the most recent discussion of the ‘constcamer’ paintings, see Floor Anna Koeleman, ‘Visualizing Visions: Re-Viewing the Seventeenth-Century Genre of Constcamer Paintings’ (PhD Diss., University of Luxembourg 2021). For the most common wall finishings of the period, see Fock, Het Nederlandse Interieur, 92-94.

[45] The portraits fit for this collection include Dirk Jansz. de Graeff (1529-1589), Pieter’s great-grandfather, dated to 1578 (in private collection, see RKD image: 146221); Jacob Dircksz de Graeff (1569-1638), Pieter’s grandfather, dated to 1625-1638 (private collection, see RKD image: 125312); Cornelis de Graeff (1599-1664), Pieter’s father, dated ca. 1643-1645 (private collection, see RKD image: 212715); of a slightly smaller size, but with the same pose, Catharina Hooft, Pieter’s mother, dated 1635 (Kunsthaus Malmedé, Cologne, see RKD image 196640); Dirck de Graeff (1601-1637), Pieter’s uncle, dated 1625-1649 (private collection, see RKD image: 124285); Andries de Graeff (1611-1677), Pieter’s uncle, dated after 1639 (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, see RKD image: 34952); Gerrit Pietersz Bicker (1554-1604), Jacoba’s paternal grandfather, dated 1583 (Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam, see RKD image: 24168); Alijd Boelens (1557-1630), Jacoba’s paternal grandmother, dated 1583 (Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam, see RKD image: 16967); Jan Bicker (1591-1653), Jacoba’s father, dated to 1650-1700 (Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam, see RKD image: 4082); Agneta de Graeff (1603-1656), to 1650-1700 (Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam, see RKD image: 4086). Interestingly, also Jan de Graeff (1673-1714), one of Pieter and Jacoba’s children who lived in this house after his father died had himself portrayed (dated around 1700, private collection, see RKD image: 231281). Similarly, Jan’s son Gerrit and his wife Elisabeth Lestevenon, who lived at the Herengracht after Jan, have similar portraits (private collection, RKD images 144314 and 144315, respectively). Some of the paintings have a painted oval frame, as in fashion since ca. 1670.

[46] Wayne Franits, ‘Young Women Preferred White to Brown’, Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art/Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek Online 46:1 (1995) 394-415.

[47] The bust-size portrait of Dirck de Graeff (1601-1637) (RKD image: 124285) was likely after the life-size portrait attributed to Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy (Hoge Raad van Adel, The Hague, RKD image: 41204). Likewise, the one of Andries de Graeff (RKD image: 34952) was after the well-studied life-size portrait by Rembrandt in 1639 (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meiste, Kassel (Hessen), inv./cat.nr GK 239).

[48] SAA inv. nr. 193 (1673), 22 July. On the making of the two paintings, one now kept at the Rijksmuseum, the other at the Saint Louis Art Museum, see Gebrand Korevaar and Gwen Tauber, ‘Gerard ter Borch Repeats: On Autograph Portrait Copies in the Work of Ter Borch (1617-1681)’, Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum 4 (2014) 348-381. DOI: https://doi.org/10.52476/trb.9852. Korevaar and Tauber hypothesise that the Rijksmuseum copy which shows important damage due to sun exposure was the copy which used to hang in the groote kamer given its large windows facing south. It is possible that the Rijksmuseum copy was the portrait hanging in the groote kamer, but it is not likely that this would have been the only painting where such level of sun damage occurred. As discussed, Jacob’s portrait was part of a series of oval-topped portraits which likely were placed together and hence would have showed the same signs of sun damage. Moreover, the inventory records two window curtains in the groote kamer (‘Twee oude groene glas gordijnen’, SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 447), so the paintings would not have been hung unprotected from sun light.

[49] SAA 76, inv. nr. 193 (1673), 22 July. Cf. Korevaar and Tauber, ‘Gerard ter Borch’.

[50] See SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 446.

[51] ‘Een Jongentje verbeeldende den Heer Cornelis de Graaf voornoemt [de Jonge] boven de schoorsteen door de oude Jan Lievensz.’ valued at 25 guilders, see SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 491.

[52] ‘Heeft Jan Lievensz. Schilder, in presentie van de Hr. Gerard ter Borgh, om mijn soon naeckt als een cupido uyt te schilderen geeijst f. 50.’, SAA 76, inv. nr. 193 (1673), 25 October, see also Sebastien A. C. Dudok van Heel, ‘In presentie van de heer Gerard ter Borgh’, in: Anne-Marie Logan (ed.), Essays in Northern European Art Presented to Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann on his Sixtieth Birthday (Doornspijk 1983) 66.

[53] SAA 606 Serie A 62: ‘op ons comptoir (zijnde jegenwoordig de kamer boven onse jegenwoordige slaapkamer […])’.

[54] See Piccoli, Pieter de Graeff.

[55] SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 452-456. The walls were covered by ‘Een gevlamt Rouaans Kamerbehangzel’ which, like the tapestry wall hangings, gave the space a luxurious touch.

[56] ‘Een schilderije verbeeldende Polsbroek; Een dito [schilderije] van Ilpendam; Twee tekeningen van Ilpendam’, see SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, p. 452.

[57] According to Houbraken, Isaac de Moucheron was still in Rome in 1697 and returned to Amsterdam in the same year. Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, 3 vols. (Amsterdam 1718-1721) vol. 3, 183.

[58] The association between female nude and lust and the power of the paintings as erotic objects are thoroughly discussed in Eric Jan Sluijter, Rembrandt and the Female Nude (Amsterdam University Press 2006) 143-163. For the list of paintings in the inventory, see SAA NA 5075, inv. nr. 5001, pp. 448-449 and note 12.