The Greening of Dutch Protestant Christianity (1960-2020)¶

BMGN — Low Countries Historical Review | Volume 139-2 (2024) | pp. 66-95 | DOI: 10.51769/bmgn-lchr.13865

David Onnekink and Suzanne Ros

Table of contents¶

- Introduction

- The greening of Dutch Protestant Christianity in four phases

- Phase I (circa 1972-1989)

- Phase II (circa 1989-2009)

- Phase III (circa 2009-2019)

- Phase IV (circa 2019-)

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

Introduction[1]¶

On 10 November 2021 Utrecht Protestant minister and climate activist Rozemarijn van ‘t Einde was arrested in the Dutch town of Zeist for occupying the lobby of a Dutch pension fund that invested in fossil fuels. She is member of Christian Climate Action (CCA), an organisation loosely associated with Extinction Rebellion (see Figure 1).[2] CCA organised the occupation in the context of the COP 26 Climate Change Conference that was taking place in Glasgow from 31 October to 12 November that year. At the same time, a survey revealed that there was a widespread feeling among Dutch Protestant youths that the church was inactive and uninspiring in dealing with the climate crisis.[3] Did these two events indicate growing alarm within Christian circles in the Netherlands about the climate crisis?

In this article we investigate whether Dutch Protestantism has witnessed a ‘greening’ in recent years. A number of scholars have claimed to observe a global ‘greening of Christianity’. They point to the plethora of Christian environmental initiatives over the past few decades and most notably the advocacy of Pope Francis. For instance, Allan Effa stated that ‘Roman Catholics, conciliars, and evangelicals speak in remarkable unison of the theological basis for the greening of mission.’[4] Others, however, believe this not to be the case. Environmental political scientist David Konisky, for instance, did extensive research on surveys between 1990 and 2015 among Christians of all denominations in the United States. He concluded that despite swelling rhetoric on ‘the greening of Christianity’, ‘environmental attitudes have not changed over the past two decades, and perhaps the level of concern among Christians has diminished’.[5] Konisky’s view is consistent with the axiomatic thesis of Lynn White, who argued in 1966 that Christianity’s impact on the environment has been destructive, because Christian theology ‘insisted that it is God’s will that man exploits nature for its proper use.’[6] The Lynn White thesis has dominated the debate on the relationship between religion and environmentalism until today.[7]

This article is positioned in this debate by investigating Dutch Protestant Christian attitudes towards environmentalism. Although the landscape of Dutch Protestantism is intricate, with a plethora of denominations, it can also be studied as a coherent movement, because it is rooted in the Reformation and has common cultural and theological traits.[8] This article serves as an exploration of Dutch Protestant engagement with the environment, which lacks a historiography.[9] It therefore presents a historical overview as well as an analysis of the greening of Dutch Protestantism from the inception of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s until 2020. We research if and how Dutch Protestant Christianity became attuned to environmentalism in recent decades. Such a historical analysis is warranted, as the implications of the Lynn White thesis are usually debated amongst theologians, philosophers, political scientists and ethicists rather than historians.[10] For instance, recently philosophers Michael Northcott and Henk Jochemsen discussed whether or not Protestant values were conducive to the flourishing of environmentalism.[11]

A historical analysis is valuable because it can reveal processes of change and steer clear of static conclusions. First, we analyse Dutch newspapers to gauge whether there was Protestant public awareness of environmental issues. Based on this we argue for a historical development in four phases, which forms the rationale for the structure of this article. For each phase then, we combine different sources to research aspects of the Dutch Protestant movement in relation to greening. An analysis of ecclesiastical policies and the activities of Protestant organisations shows whether there was an active sense of a ‘green’ mission among Dutch organisations. Surveys, finally, provide insight into personal attitudes of individual Dutch Protestants more generally. We aim to pilot a historical understanding of the greening of Dutch Protestantism, but for practical reasons, the scope of this article also has limitations. We did not study political parties, Catholic believers and churches, generational, denominational or regional differences, each of which would require extensive additional research.

We argue that there was a discernable ‘greening’ of Dutch Protestant Christianity in the Netherlands between about 1960 and 2020, but that this process was checkered and not continuous, hence occurring in phases.[12] We aim to identify these phases and lay bare some of the drivers of the process. We also show that different patterns evolved for individual Protestants, public interest, churches and organisations. Dutch Protestantism was adaptive and its relationship with environmentalism was complex and dynamic.

The greening of Dutch Protestant Christianity in four phases¶

Before we start our chronological analysis, we need to structure the period under revision. There is currently no concise historical analysis of the relationship between Dutch Protestantism and environmentalism. Short narratives and timelines are available and provide an overview of the most important events.[13] However, a deeper understanding requires the provision of a more comprehensive overview. We will do so by tracking public awareness of Dutch Protestants of environmental issues, based on a quantitative analysis of relevant articles in confessional newspapers between 1960 and 2020. This analysis reveals a discernable chronological development in Protestant awareness of environmental themes.[14] Based on these data, we state that this awareness developed in four phases, with peak moments around 1972, 1989, 2009 and 2019. We perceive these news articles as reflections of the newspaper’s ideologies, aligning with media historian Marcel Broersma’s assertion that newspaper media ‘construct the news from an ideological perspective and thus structure reality for their audience.’[15] Essentially, this extensive collection of sources offers a comprehensive depiction of the social world of Dutch Protestant media.

We combine data from Digibron (a database for Dutch confessional magazines and newspapers, most notably the conservative orthodox newspaper Reformatorisch Dagblad), Delpher and Nexis Uni (databases for newspapers).[16] We employ distant reading to map Protestant climate change discourse by analysing textual data, reading texts through counting, making graphs and maps or in other words, visualising data.[17] We also take a comparative in-depth look at the national Protestant newspaper Nederlands Dagblad by comparing it to a more secular newspaper, de Volkskrant.[18] Through the compilation and analysis of these sources, we can provide an overview of the Dutch Protestant media landscape spanning from 1960 to 2020.

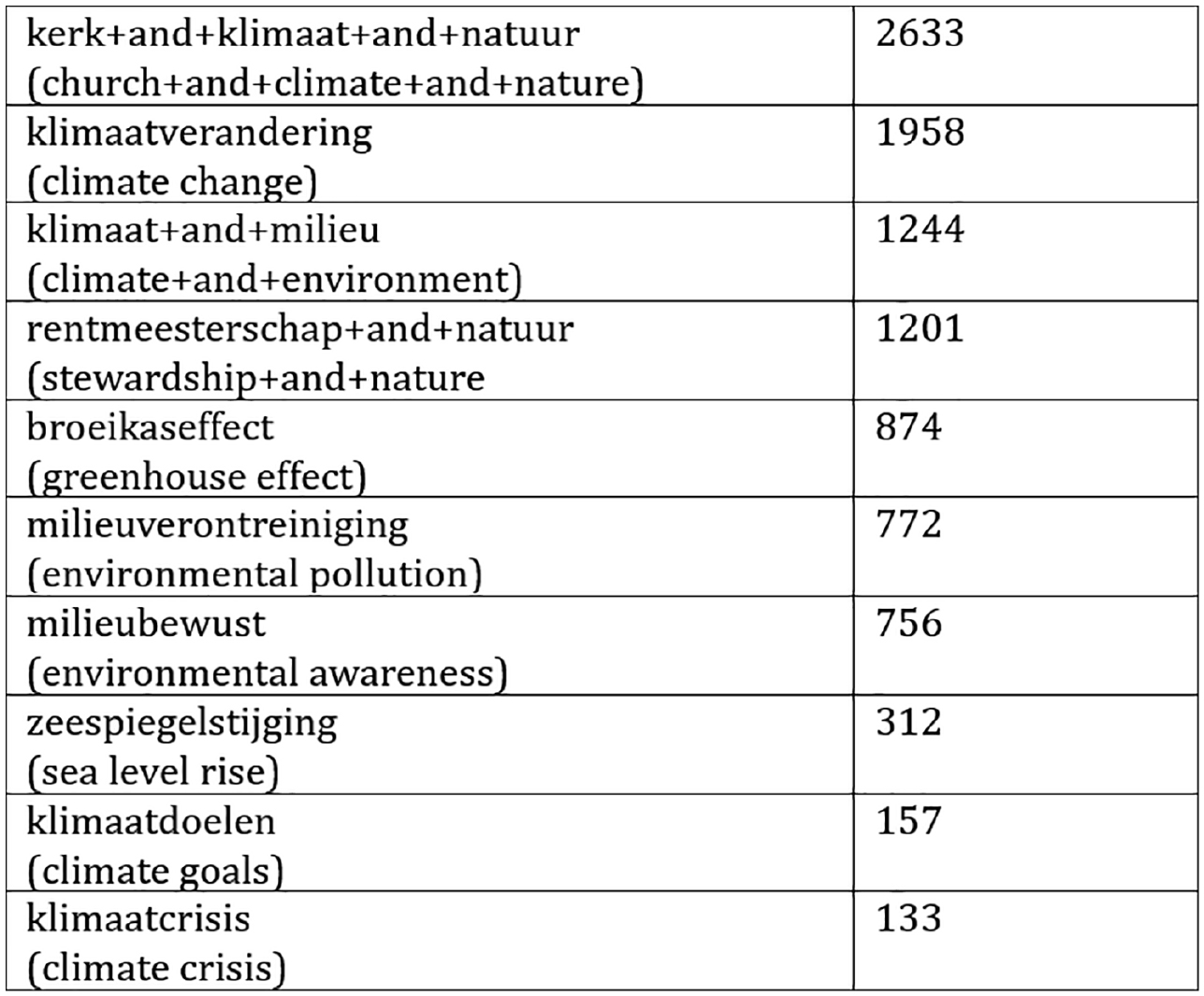

In a first attempt to explore the emergence and development of climate change discussion in Protestant news articles, we conduct a semantic field exploration. We applied a query of several terms concerning climate change to Digibron’s metadata [see Chart 1].[19] In constructing the corpus, we compared commonly used and recurring terms from relevant historiography discussing Protestantism in relation to the environment with terms found in the databases. We then incorporated these identified words and queries into our analysis.[20]

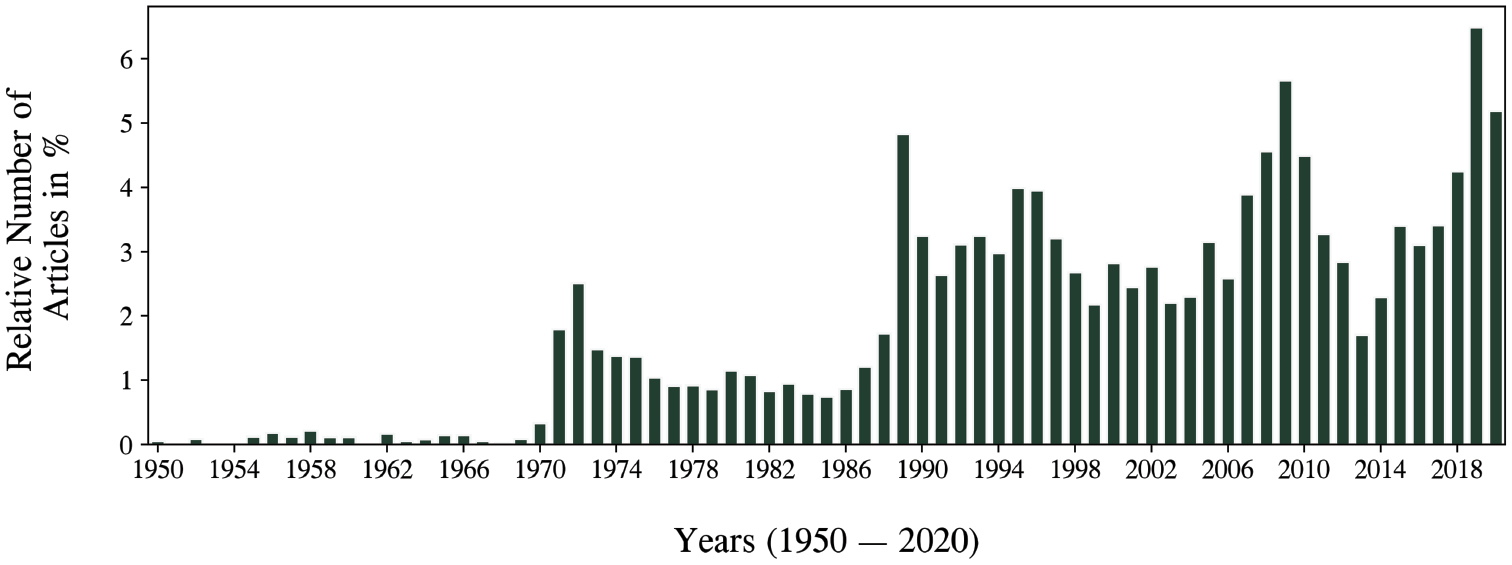

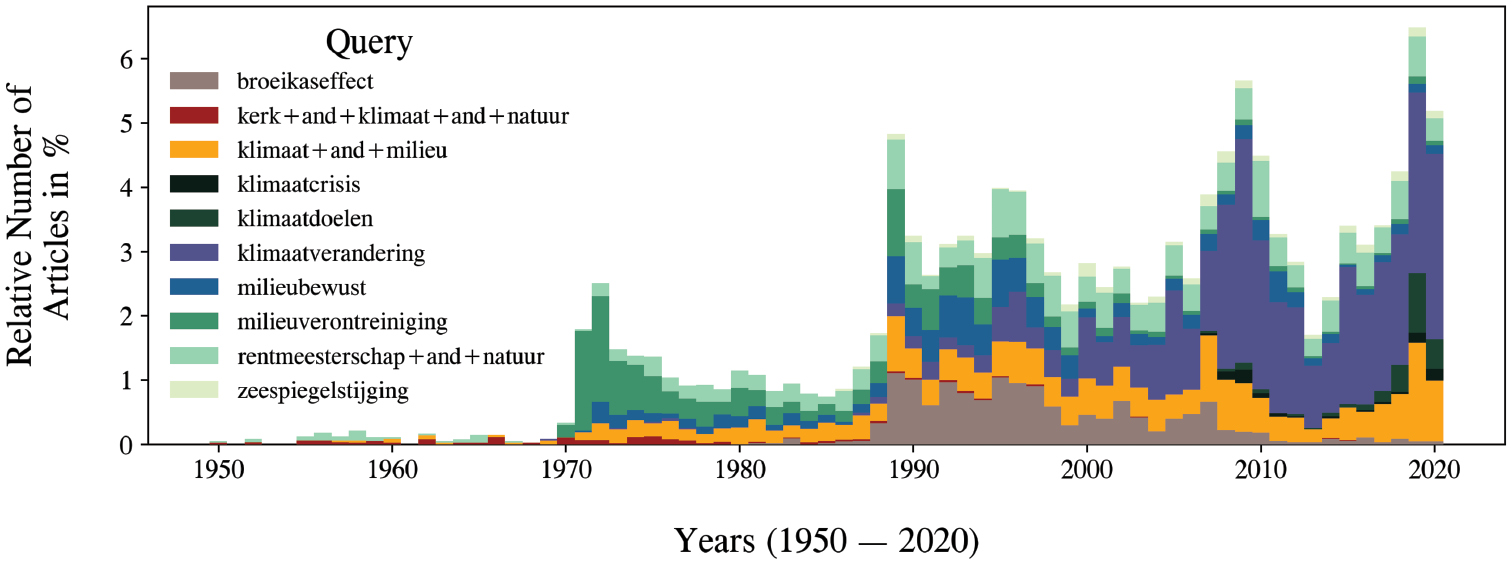

Only terms that yielded more than 120 articles or hits in the sources of the database were considered, and their translation into Dutch closely followed the English terms from the mentioned historiography.[21] Ultimately, these methods help determine the debate on the level of etymological and contextual histories. The distribution of these articles per year produces Graph 1, whereas Graph 2 shows the relative frequencies per search term.[22]

These graphs show a significant increase of articles in Dutch newspapers about climate change around the years 1972, 1989, 2009 and 2019. The timing is consistent with what Jan Luiten van Zanden and S. Wibo Verstegen describe as the ‘barometer of the Dutch environmental movement’, namely the development of Natuurmonumenten (the Society for Preservation of Nature Monuments), which saw rises in membership after 1971 and around 1990.[23] Graph 2 shows notable developments, such as the words that characterised the debate in its beginning (‘environmental pollution’), words that are present throughout the debate (‘stewardship’ and ‘nature’) and the words that are relatively new (‘climate change’ and ‘climate goals’). The graph overall shows the expansion of environmental vocabulary with the introduction of terms with a more solution-oriented focus and proposing climate goals necessary in solving the crisis.

A comparative analysis between the Protestant Nederlands Dagblad and the more secular de Volkskrant expands our understanding of the way in which Christian ecological engagement contrasts with the ecological reporting of Dutch secular media. Nederlands Dagblad, ranking second in the Protestant media landscape alongside the Reformatorisch Dagblad, provides a unique perspective into a distinct branch of Dutch Protestantism, representing the orthodox Reformed (Hervormd Vrijgemaakt) currents within Dutch Protestantism, which sets it apart from the more conservative Protestant newspapers featured in Digibron. Furthermore, the Nederlands Dagblad appeals to both orthodox Reformed and neo-Calvinist readers, as well as evangelical readers, with a majority of its readership supporting Dutch Christian political parties, namely the ChristenUnie and the CDA, and to a lesser extent, the SGP. Along with NRC and Trouw, de Volkskrant belongs to a representative selection of secular newspapers in the Netherlands in the second half of the twentieth century. These newspapers either had some of the largest circulations in the country or appealed to newer generations. Historian Frank van Vree suggests that de Volkskrant experienced a significant cultural shift during the 1960s and 1970s.[24] He contends that de Volkskrant underwent a transformation from being a Catholic-oriented newspaper to becoming a modern secular quality newspaper. This transformation involved the introduction of a new editorial team, and innovative journalistic approaches aimed at reflecting and inspiring social change. The newspaper sought to appeal to a younger, more progressive audience, embodying the voice of the new generation.[25]

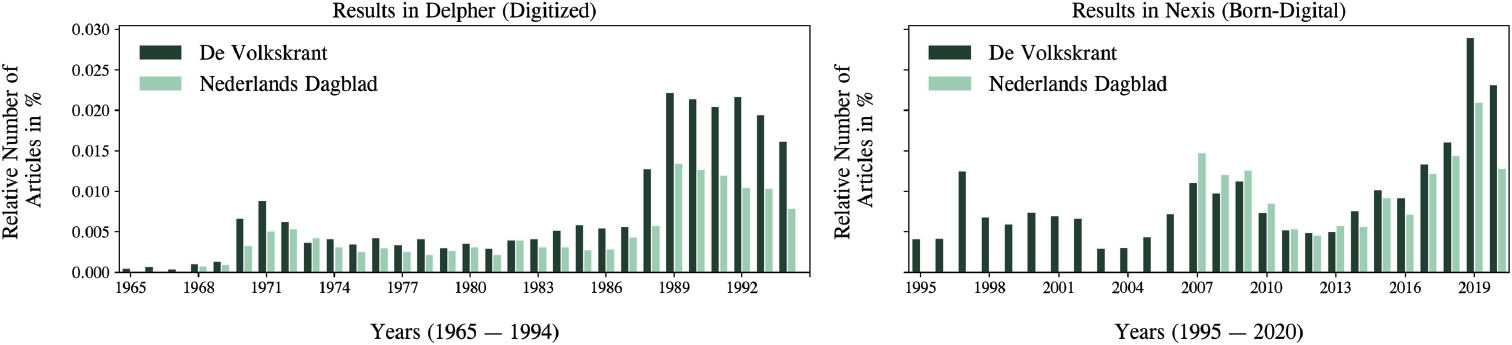

These two newspapers do not fully represent Protestant or secular reporting on climate change. However, a comparison between Nederlands Dagblad and de Volkskrant is indicative for differences and similarities in the climate debate. This allows for an estimation of the relative speed of the greening of Protestantism compared to the Dutch society at large. Using the same search terms as for Digibron, datasets were compiled for both newspapers and compared by employing Delpher and Nexis Uni. The results are visualised in Graph 3.[26] The graph shows that there was a mild increase in climate discourse around the years 1971 and a clearer increase of articles in the period between 1989 and 1994. A next peak occurs between 2007 and 2009 and a final one in 2019.[27] Thus the four conceptualised phases are confirmed in this study of Nederlands Dagblad and de Volkskrant. It also appears that the pacing and timing of Protestant reporting is reasonably in line with the secular reporting.

Phase I (circa 1972-1989)¶

On the basis of this panoramic quantitative survey of newspapers, we propose four chronological phases of the development of green awareness amongst Dutch Protestants, which will be substantiated in the following paragraphs. We argue that the first phase started around 1972 and was triggered by growing attention to the environment in the wake of the establishment of the Club of Rome in 1968 and its report in 1972.[28] This is consistent with the claim of Van Zanden and Verstegen, who characterised the report in combination with the 1973 oil crisis as a peak moment for public environmental awareness in the Netherlands more generally. It is also in line with the more recent study Wat we toen al wisten. De vergeten geschiedenis van 1972 by Geert Buelens.[29]

The 1960s saw scattered early beginnings of environmental awareness by theologians in the Netherlands. A piloting theological work on the environment was published by Hendrik Berkhof in 1960.[30] In 1970, the American Reformed philosopher Francis Schaeffer, in his Pollution and the death of man, was one of the first Protestant conservatives to engage with Lynn White. In 1973, Schaeffer’s pivotal study was translated in Dutch.[31] In July 1971 the Dutch Reformed Council of Churches organised a two-day conference in Oegstgeest to discuss how theology could inform care for the environment.[32] This interest peaked around 1972. Hans Bouma, a Protestant author and animal activist in the 1970s, tracked the start of a theological reorientation on ecology to the 1972 special issue entitled In de greep van het milieu (In the grip of the environment) by the Dutch Council of Churches.[33] Dutch confessional newspapers widely discussed ecological engagement around the 1970s. For instance, the Nederlands Dagblad discussed early initiatives combatting environmental pollution. In response to an oil spill in January 1971, the newspaper reported that ‘the Dutch people must be educated to a new sense of responsibility. That is also a matter of self-preservation, for the pollution, the poisoning, the extermination of countless creatures of God will increasingly turn against man himself.’[34]

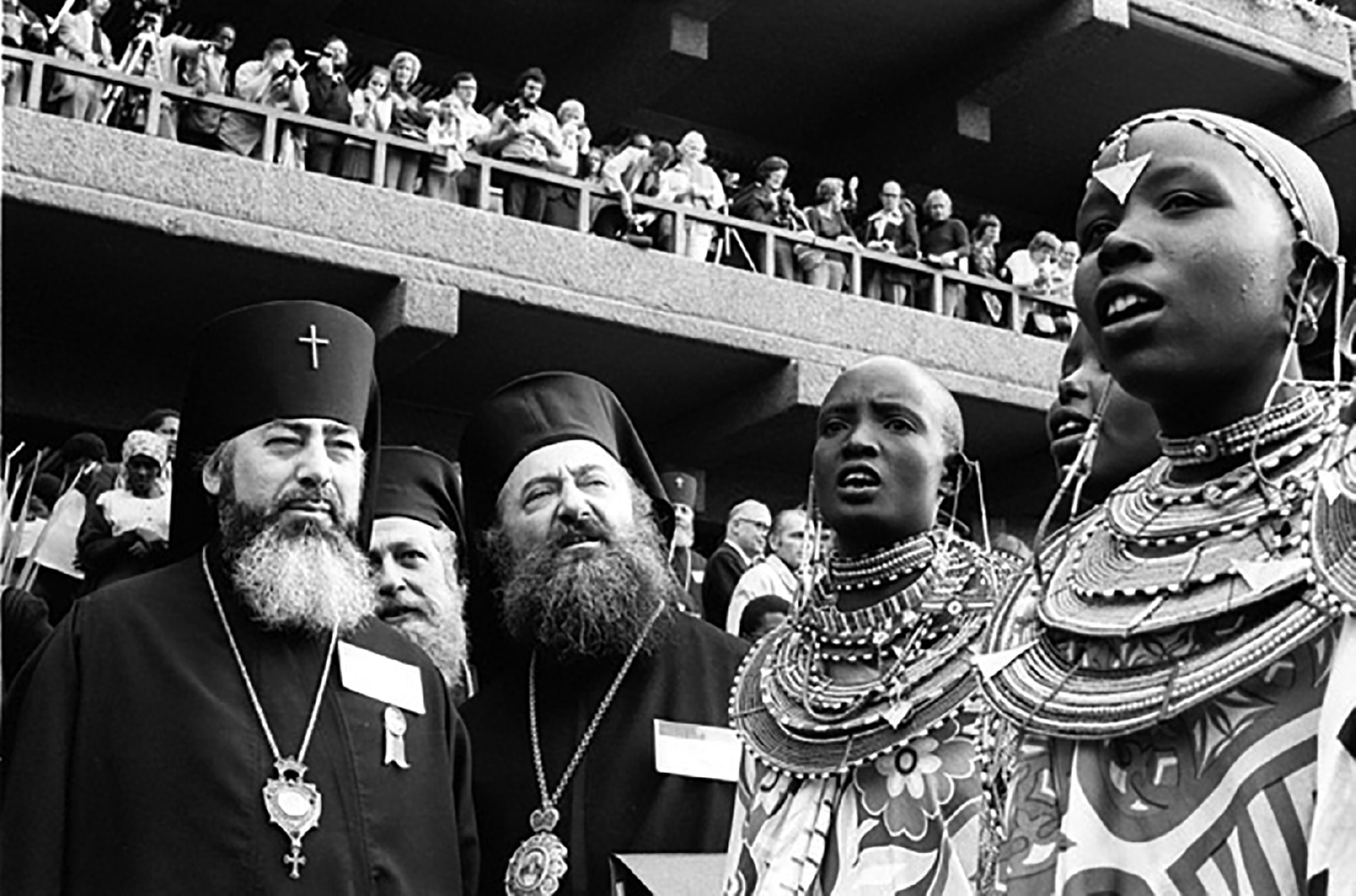

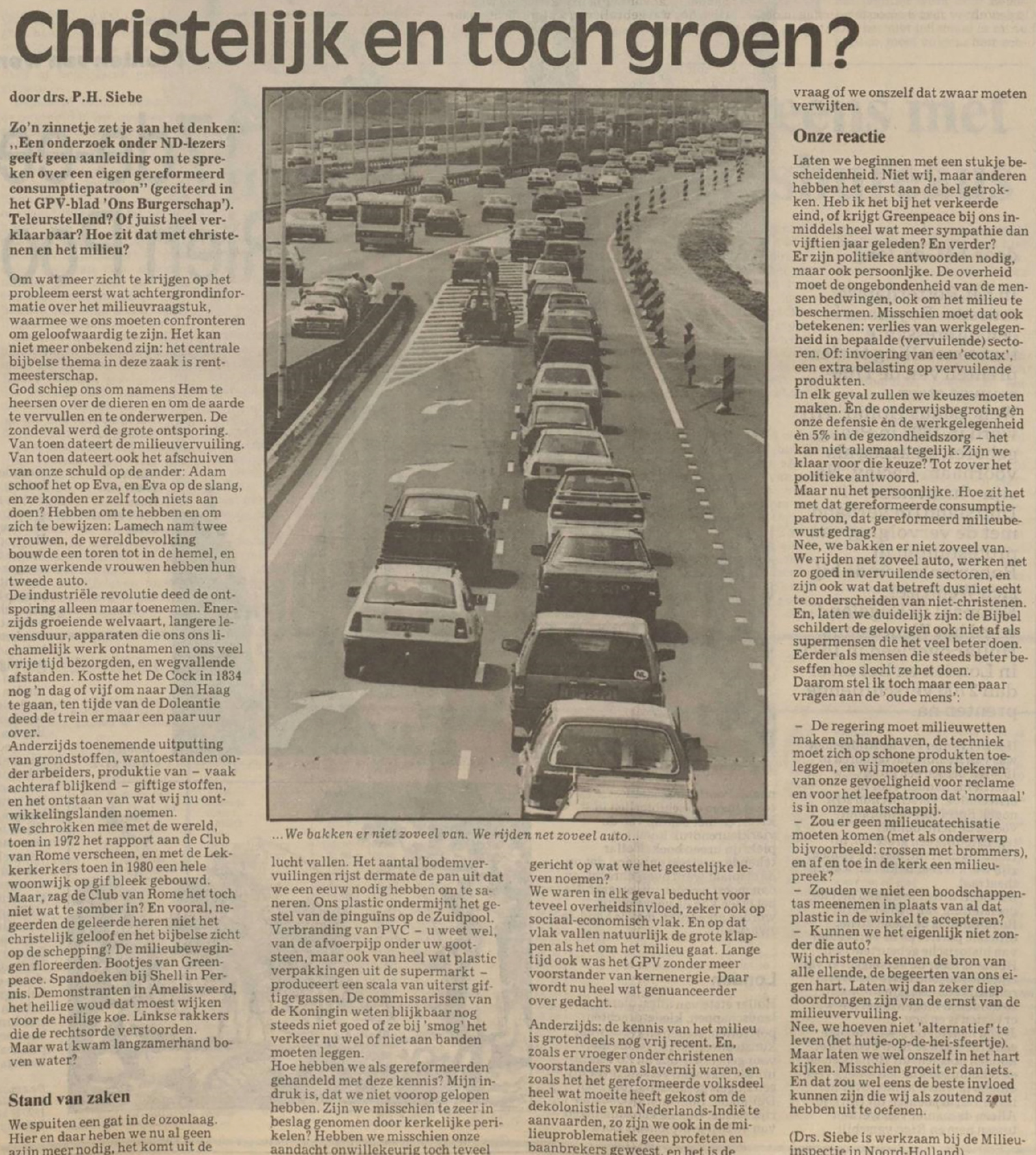

Newspapers show a steady decline in interest in environmental issues after the 1972 peak, but a renewed rise in the late 1980s. This coincided with the public concern about acid rain, caused by sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and ammonia dissolving in rain clouds. Dutch Parliament ordered a thorough investigation into the matter in 1983 and in the late 1980s a public debate ensued.[35] During that same period the ‘Conciliar Process’ was kick-started by the World Council of Churches in 1983 in Vancouver. It focused on the combined attention to ‘Justice, Peace and Care for Creation’, and thus ecclesiastical environmentalism gained traction again (see Figure 2). Although Dutch churches were losing ground in the public sphere,[36] they remained vocal through the Conciliar Process. In 1986 the working group Kerk en Milieu (Church and Environment) was established within the Dutch Council of Churches. Inspired by the German Manifest zur Versöhnung mit der Natur; die Pflicht der Kirchen in der Umweltkrise (1984), Kerk en Milieu published its own manifesto in 1988 and organised two conferences in 1986 and 1987.[37] The newsletter of Kerk en Milieu counted up to 2700 subscribers.[38] Around the same time environmental awareness dawned in evangelical circles with the publication of Als het water bitter is (When the water is bitter) in 1988 by theologians and missionaries Evert van der Poll and Janna Stapert (see Figure 3).[39] By the end of the 1980s, environmental activism was gaining steam again in mainstream Protestant churches.

Phase II (circa 1989-2009)¶

During the first phase, churches thus started to engage with the issue of environmental pollution, although the newspaper analysis shows a rise and fall in public Protestant awareness. The climate crisis, which had been relatively abstract in 1971, became increasingly tangible at the end of the 1980s.[40] As the Nederlands Dagblad noted in 1989: ‘There is a growing awareness that cleaning our environment and preventing further pollution costs money.’[41]

The second phase in our analysis starts in 1989, with many newspaper articles being published on environmental policy reports and climate summits. In 1989 the Nationaal Milieubeleidsplan (NMBP, National Environmental Policy Plan) and the report Zorgen voor morgen (Take care of tomorrow) of the Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) highlighted the deep concern about fertilisers, acid rain and the greenhouse effect that had dominated public debates in the 1980s. Published by the Dutch Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment, the NMBP was widely regarded as a significant milestone in environmental policy within the Netherlands.[42] In the Nederlands Dagblad environmental problems were discussed in the political arena at regional, national, multilateral and global levels (see Figure 4).[43] Similar to the articles presented in Digibron, the Nederlands Dagblad paid considerable attention to the NMBP.[44] Van Zanden and Verstegen confirm the timing of our phase II: ‘In these years 1988-1989 concern about the environment in the Netherlands temporarily peaked’.[45]

This phase also saw an expansion of ecclesiastical activities as well as a definite increase in public support. The greening in Dutch churches reached a peak around 1989, instigated by the activities in the context of the Conciliar Process, the obvious environmental pollution problems and the publication in 1987 of the UN-commissioned Brundtland report, which put sustainable development firmly on the international agenda. In 1989 the Secretary-General of the Reformed (Hervormde) Church, Wim van der Zee, reformulated church policy in the face of the ‘increasingly spreading process of environmental pollution and exhaustion’.[46] ‘Creation care’ had been the third and undervalued theme of the Conciliar Process, which had emphasised the ‘Peace’ and ‘Justice’ components ever since its inception in 1983. According to a 1988 article in the Dutch magazine Kleine Aarde (Small Earth), published by a pioneering sustainability centre, ‘people in churches were very well informed on the issues of peace and justice. But the environment?’[47] It may have been undervalued for lack of an ecclesiastical tradition so far of dealing with the environment, whereas peace and justice were themes with deep historical roots in church policy.[48] Realisation dawned that these three themes were inextricably connected. Moreover, they resonated with concerns about acid rain and greenhouse gasses that figured largely in public debates in the 1980s.

In 1989 the Dutch Council of Churches organised four overbooked symposia on the ‘Integrity of Creation’, attended by two thousand people.[49] Organiser Jaap van der Sar, co-founder of Kerk en Milieu, introduced this as a new phase, claiming no originality: ‘We bring to the church that which has already been invented. What the environmental movement has been doing for years, we translated to our constituency’.[50] Relations between Protestant churches and environmental organisations had been absent or even adversarial, but now green organisations were invited and ‘the environmental movement and churches have recognised each other as allies.’[51] Moreover, there was a call for churches to take the lead in issuing a ‘moral agenda’ for creation care.[52] De Kleine Aarde magazine concluded: ‘The environment now has the full attention of the church.’[53]

The successful 1989 symposia were repeated in 1990 and 1991, but despite the wide public appeal of these events, interest in environmentalism faded in the 1990s. Some observers argued that this was due to the overly ambitious goals that were set.[54] At the same time, new initiatives continued to be developed, such as a visit in 1995 from delegates from Zirrcon which had initiated a tree planting project in Zimbabwe.[55] In 1998 the Christelijk Ecologisch Netwerk (CEN, Christian Ecological Network), part of the European ECEN, was established by conservative and evangelical Christian institutions, following its American counterpart, the Evangelical Environmental Network which produced the 1996 Evangelical Declaration on the care of creation. A landmark was the establishment in 2003 of the Dutch branch of the evangelical A Rocha, the only Dutch Protestant ecological organisation. Despite all these efforts Remonstrant minister At Ipenburg observed that ‘churches sometimes have difficulty’ with operating the third leg of the Conciliar Process.[56] The major environmental issues of the 1980s and the knock-on effect of the Conciliar Process activities produced growth in public support and easing relations with secular environmental organisations, but public interest in environmentalism waned in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Phase III (circa 2009-2019)¶

A third phase of the greening of Dutch Protestantism started around 2009, the year of the COP 15 Climate Summit in Copenhagen. Newspapers show a rise in interest from about 2007, a peak in 2009, followed by a slow decline until 2014, and an increase from 2015, possibly as a result of the Climate Summit in Paris. Religious institutions and their initiatives were discussed more frequently in the Nederlands Dagblad reporting in 2009. Following Copenhagen, at least 25 articles mention the role that the Church has or should pursue in global climate action.[57] Examples of ecclesiastical initiatives were cited and articles theologically expanded more broadly on the significance of climate change for Christians.[58] The Nederlands Dagblad started highlighting religious initiatives that provided aid for the victims of climate change.[59] de Volkskrant reveals a similar development in which climate change and humanitarian aid are connected.[60]

Phase III was characterised by more public commitment from churches. In 2009 a campaign entitled ‘Countdown to Copenhagen’ was set up by the initiators Interkerkelijke Coördinatie Commissie Ontwikkelingssamenwerking (ICCO, Interdenominational Coordination Committee for Development Cooperation) and Kerk in Actie, urging the Dutch government to ‘make just and effective global climate agreements’.[61] The World Council of Churches and the European Council of Churches rallied in support. 900 churches rang their bells on the occasion of the climate summit in Copenhagen to draw attention to Christian responsibility in the preservation of creation.[62]

A second characteristic was the increasing role of Christian organisations. In 2009 Kerk in Actie and ICCO established the Fair Climate Fund, an initiative to finance and implement Climate Projects. In 2011 the evangelical NGO Tear and Kerk in Actie set up the Groene Kerken (Green Churches) platform, boasting the participation of over 450 churches in 2024 and initiating cooperation with green mosques.[63] In 2011 the Noach Coalitie was established, coordinated by Dutch Christian author and eco-activist Martine Vonk, to choreograph green church activities. It fused with Micha Nederland in 2013, a broad network of churches and Protestant NGOs and social organisations.[64] In 2017 the Green Churches connected to ECEN. This period also saw a denominational widening, as Dutch evangelical organisations, that were hitherto lukewarm about environmental issues, were increasingly on board.[65]

The growing involvement of Christian organisations in Dutch environmentalism is noteworthy. Research on global RNGOs (religious NGOs) is thin, but they form an important segment in the world of developmental aid and are increasingly the subject of scholarly interest.[66] Carolyn Peach Brown trailblazed research on green attitudes of US RNGOs in 2014. She found that Christian developmental organisations started to understand that climate change impacts poverty and welfare, and ‘this has led to FBOs [Faith Based Organisations] being active in both climate change advocacy and project implementation’.[67] Even so, in her case study on the world’s largest Protestant NGO, World Vision, Peach Brown found that the organisation in practice had only limited interest in environmental change.

In the Netherlands, many Protestant RNGOs are represented by three umbrella organisations: the Nederlandse Zendingsraad (NZR, Protestant mainstream missionary organisations), Missie Nederland (evangelical missionary organisations) and Prisma (Protestant aid organisations).[68] Together they comprise about 150 mostly Protestant organisations, which are locally and globally connected.[69] Many of these organisations are ecumenical, but some also directly or indirectly draw from specific Reformed, Lutheran or evangelical denominations.[70] Some organisations are a member of more than one umbrella group. We conducted an analysis based on the annual reports of these organisations that spans the length of phase III, using the key years 2010 and 2020 (the actual reports were based upon data on 2009 and 2019, precisely the beginning and end of phase III). Our analysis was not selective and all organisations were considered, but for many of these annual reports were either not available (anymore) or limited to financial information. Our analysis was ultimately based on the reports of 72 RNGOs.

We devised an indicator to measure how ‘green’ these organisations were. The categorisation is heuristic and empirical and was based on the following question: to what extent did Dutch organisations have an environmental policy or awareness? We used the following categories: dark green (the RNGO has an active green core programme that benefits or focuses explicitly on the environment), medium green (the RNGO takes measures in the workplace such as solar panels and aids people who suffer from the effects of climate change), light green (environmental issues are mentioned in the report but not functionally connected to activities), white (no mention of environment in report) and orange (the RNGO is skeptical of environmental issues) (see Appendix Table 1).

A comparison between the situation in 2010 and 2020 yields an obvious greening of Dutch Protestant RNGOs. If we count only organisations for which reports of both years were available, the figures are as follows: the number of dark green organisations between 2010 and 2020 rose from 4 to 8; medium green from 8 to 15; light green from 0 to 2. Examples are the evangelical school De Passie, which was not involved with the environment or climate change in 2010, but started to develop educational material on these themes that were implemented by 2020. The Gereformeerde Zendingsbond (GZB), a Reformed missionary organisation which draws support from conservative pietist Calvinism, did not concern itself with the environment in 2010. By 2020, however, a green programme was implemented, inspired by ‘care for creation’ and consisting of a variety of projects, such as compensation for air travel, the planting of trees in Mozambique and public lectures on ecological justice.[71]

Based on the 2020 annual reports we concluded that none of the 72 organisations were explicitly sceptical or critical of environmentalism, but 41 (57 per cent) did not mention the environment, climate change or sustainability at all. Six organisations (8 per cent) mentioned sustainability or the environment but did not act upon it (light green). Seventeen organisations (24 per cent) mentioned the importance of the environment and took responsible measures in the workplace or aided victims of climate change (medium green). By way of example, 3xM (More Message in the Media), which focused on broadcasting the gospel in Africa and Asia, aimed to be a climate-neutral organisation and invested in compensating air miles by planting trees and asking employees to live locally.[72] Eight organisations (11 per cent) can be qualified as dark green, and had projects that are relevant for the environment. These were, for instance, the Evangelische Omroep, the evangelical broadcasting organisation, which is not focused on the environment as such but aired several nature documentaries. These eight organisations include conservative Reformed, evangelical, Lutheran or non-denominational, and therefore no denominational pattern is discernable.

Thus in 2020, 8 out of 72 organisations were actively engaged with the environment. If we adopt a more stringent selection, only one RNGO (1.5 per cent), the evangelical A Rocha, is exclusively concerned with the environment. The picture changes radically when we analyse financial resources allocated to the environment. The organisations we researched have altogether an annual income of just over one billion euros (€ 1,031,936,672), but A Rocha has an annual budget of about € 100,000. From this perspective, only 0.01 per cent of the annual budget of the here studied Dutch RNGOs is allocated to explicit environmental organisations. Thus, although there is a visible greening among Protestant NGOs, the environment was not something of major concern in phase III.

Most Protestant RNGOs were thus not or only partially attuned to the environment, and Christian mission was usually not thought to include creation care. Even so, it is plausible to suggest that there was simply no room for green RNGOs, since the Netherlands already hosts a number of secular environmental organisations. Possibly Dutch Protestants channeled financial resources to these organisations rather than Christian ones. Peach Brown found in 2014 that many employees of the global Christian organisation World Vision were deeply concerned about the environment, even if the organisation itself was lukewarm. Many respondents in an American survey connected their pro-green stance to their faith.[73]

Private faith may therefore be a more reliable indicator of the greening of Christianity than an analysis of the activities of Christian organisations. Unfortunately, large-scale surveys on green attitudes that include religion as a factor are not available in the Netherlands, with the exception of the report of the Sociaal and Cultureel Planbureau (SCP, Netherlands Institute for Social Research) published in May 2024.[74] Moreover, there are no pre-2010 surveys available that gauge Protestant engagement with the environment, possibly an indicator of a relative lack of interest in that connection. Even so, in phase III several surveys have been conducted that are indicative for the greening of Protestantism. In 2010 Forum C, a platform of Dutch Christian scientists, published a report on attitudes towards sustainability amongst orthodox Christians (among 538 respondents acknowledging a Reformed, evangelical, Baptist or Pentecostal identity). In 2012 and 2014 Micha Nederland, a Protestant network committed to furthering the Sustainable Development Goals, conducted surveys among over 1100 respondents about issues of sustainability and justice. It distinguished between Catholics, various Dutch Reformed groups (PKN, orthodox gereformeerd, bevindelijk gereformeerd) and evangelicals, as well as non-Christians for comparison.

The Micha Monitors show that the differences in environmental attitudes between Protestants and non-Christians are unremarkable. Christians donate and volunteer substantially more to good causes in general than the average Dutch citizens.[75] When it concerns the environment, however, the discrepancy is minimal. The Nederlands Dagblad concluded that ‘Christians deal with creation care very much like other Dutchmen. The topic is not coming to life.’[76] The 2012 Micha Monitor showed that Christians cared slightly more about the environment in general than the average Dutch person, but significantly lower where it concerned animal welfare.[77] A relatively small minority (2 per cent PKN, 5 per cent bevindelijk and orthodox Reformed and 6 per cent evangelical) believed that people cannot impact the environment anyway, which is not very different from Dutch society at large (5 per cent).[78] When it comes to practice, Protestants scored better than the general Dutch public, for instance when it concerns separating waste, lowering temperature at home and taking a bike or public transport instead of a car, but score slightly lower when it concerns the use of sustainable products.[79] Protestant environmentalism was thus mostly in step with mainstream Dutch society, even if different accents are discernable. Only one in seven churches maintained relations with environmental organisations, and if they did it was mostly with Protestant organisations such as A Rocha.[80] It thus seems that individual Protestants maintained more contacts with secular green organisations than churches did.

What inspired Dutch Protestants to become environmentally active? Robin Globus Veldman argued that ‘faith communities are uniquely placed to bring about transformation that is needed to address the roots of the climate change problem’.[81] Mary Evelyn Tucker, who co-established the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, likewise stated that ‘religions are key shapers of people’s world views’ and can potentially contribute to environmental action.[82] Recent psychological research confirms that an emphasis on the importance of Christian stewardship is capable of changing people’s attitudes towards the environment.[83] Indeed, according to the 2012 Micha Monitor, between 70 and 85 per cent of Protestants (depending on which ‘current’) indicated the importance of the church in shaping attitudes on lifestyle. However, only about 20 per cent of churches paid substantial attention to the theme of sustainability, with evangelical churches scoring significantly lower than Reformed.[84] In the 2014 Micha Monitor this percentage showed an increase, especially for evangelical churches.[85] The 2024 report of the SCP, the first survey in the Netherlands to address the impact of religion on environmental attitudes, largely confirmed these insights. Dutch Christians in general and Protestants in particular are influenced by their faith but not by their denominational affiliation when it comes to attitudes towards the environment, but their behaviour in practice is fairly consistent with non-religious Dutch inhabitants.[86]

The surveys thus show a disconnect between the churches and individual beliefs. The Forum C report of 2010 concluded that ‘not the church but faith inspires to green action.’[87] Looking back in 2020, Jaap van der Sar, who initiated the 1989 Conciliar Process conference, concluded that the green process was energised by the commitment of individual believers, not so much churches.[88] Illustrative for this conclusion is the fact that the 2010 Forum C survey found that the two most inspirational figures for Dutch Protestant Christians were Jesus and Al Gore.[89] It suggests that private faith and the environmental movement, rather than Christian organisations and churches, have been key in shaping Dutch Protestant green attitudes.

Phase IV (circa 2019-)¶

A fourth phase begun around 2019 and coincided with a growing feeling of urgency about climate in Dutch society at large following COP 25 in Madrid and the European Green Deal of December 2019, aimed to make Europe climate neutral in 2050. Moreover, the government took stringent measures to battle the nitrogen crisis that resulted from large concentrations of ammonia from animal manure in agriculture. In July of 2019, temperatures in the Netherlands passed an extreme 40 degrees Celsius for the first time ever, making climate change tangible. Dutch science journalist Maarten Keulemans concluded in December 2019 that ‘Climate change is for real now’.[90]

The new phase is typified by intensified environmental awareness and more willingness to undertake direct action. In June 2019 Christian Climate Action was established, loosely associated with Extinction Rebellion. It aimed for ‘non-violent direct action and public witnessing with regard to the climate and ecological crisis’.[91] CCA organised a series of public and radical actions, such as the occupation of the pension fund lobby in Zeist in November 2021 and the participation in the A12 motorway blockade on 27 May 2023. Protestant organisations were active as well. In 2020 Micha Nederland published a Green Manifesto, Het Groene Normaal.[92] A series of Groen Gelovig conferences in 2019, 2021 and 2023 were drawing many participants. On 30 October 2021 the evangelical NGO Tear organised the Justice Conference and invited Katherine Hayhoe, a renowned US evangelical climate scientist, as keynote speaker.[93] Evangelicals thus became more prominently involved and climate action became more radical. Climate awareness was becoming more mainstream among RNGOs, witness for instance publications and news items of the Dutch Missionary Council.[94]

Churches felt the pressure from their constituencies. On 4 October 2021 almost two hundred predikanten signed a letter urging the Board of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands (PKN) to take the lead rather than follow suit in the public debate about climate action in the run-up to the World Climate Summit in Glasgow.[95] Pope Francis’s Laudato si’ (2015), stating that ‘climate change is a global problem with grave implications’, gained traction in Protestant circles worldwide.[96] Internationally, interfaith alignment emerged in the run-up to the 2021 Glasgow global summit, when the Pope, the Orthodox Patriarch and the Archbishop of Canterbury issued a joint statement in which they stated that ‘Caring for God’s creation is a spiritual commission’.[97]

Our newspaper analysis shows an increase in attention to environmental issues ever since 2015, peaking in 2019. Newspapers in 2019 wrote about several climate summits, such as New York and the COP 25 conference in Madrid. More importantly, a sub-debate evolved on the ‘nitrogen crisis’ in the Netherlands. In Dutch confessional newspapers between 2019 and 2021, 145 articles were published on this topic. Protestant news articles voiced strong opposition to the government and its approach to the issue.[98] For the Nederlands Dagblad the climate crisis seemed to have developed into an irrevocable state. A recurring theme in its reporting was the discussion on the role that churches should take in the climate debate. In March 2019 the Green Churches called upon church members to join the Climate March in Amsterdam and organised an ecumenical service. This also caused considerable dissent amongst its followers, who accused churches of adopting an ‘opportunistic’ stance.[99] The data and interpretation show how Protestant reporting on climate change became increasingly urgent and solution-oriented.

Surveys show a definite greening in this period. In 2021 Tjirk van der Ziel, researcher at the Christelijke Hogeschool Ede, published his 2019/2020 survey of environmentalism within Dutch Reformed churches (PKN). He found that up to 50 per cent of churches paid attention to sustainability in sermons, which seems to indicate an increase with regard to a decade earlier, even if the different formats of the surveys makes this comparison difficult.[100] A large percentage of PKN churches had been developing green activities in recent years, such as using solar panels (27.7 per cent), reducing the use of plastic (81.4 per cent) and allocating ecclesiastical grounds as green spaces (up to 40 per cent).[101] A 2021 survey amongst Protestant youth showed that two thirds believed in the importance of climate action (70 per cent mainstream, 56 per cent evangelical), and many considered the church too passive when it comes to climate action.[102] A new generation thus inaugurated a new phase in the greening of Dutch Protestant Christianity.

Conclusion¶

In this article we argued for a progressive greening of Dutch Protestantism between 1960 and 2020 in four phases. Between 1960 and 1970 there was some interest within Protestant circles in environmentalism, but it was limited. The first phase was kick-started around 1972 by the Club of Rome report and saw the emergence of green awareness in newspapers and in churches. The second phase started around 1989 and was inspired by the Brundtland and NEPP reports and public debates about greenhouse gasses. It inaugurated a broader appeal to a general Protestant public. The third phase started around 2009 and saw the onboarding of evangelicals as well as the expansion of organisations and initiatives such as the Green Churches and Micha. It also witnessed growing awareness amongst Protestant NGOs of the climate crisis. Phase four started around 2019 and was speeded up by the climate crisis urgency. It was characterised by public dissatisfaction with ecclesiastical leadership and more vocal public calls for climate action. In each phase the peaks were followed by a steady decline and then rise in public awareness. The peaks were usually fueled by urgent environmental problems or political developments.

The four phases show that over the past five decades there has been a definite greening of Dutch Protestantism, which has shown itself to be remarkably adaptive. However, although churches were increasingly active, they have not set the agenda. It appears that urgent environmental concerns and secular developments were vital drivers of the greening of Dutch Protestant Christianity. Evidence from surveys shows that environmental awareness and green attitudes of Dutch Protestants are in step with the Dutch population at large, but that they are inspired by their personal beliefs rather than church leadership. Evidence from the RNGO reports shows a definite greening between 2010 and 2020 but also underscores the marginal amount of resources channeled into environmental protection by Christian organisations. These findings are at odds with Konisky’s conclusions. It shows that the case of the United States, where many Protestants are not attuned to environmentalism, should not be generalised. In the Netherlands, there was a checkered but consistent greening of Protestantism.

Footnotes

[1] The authors wish to thank the members of the History of International Relations seminar group at Utrecht University (especially Alessandra Schimmel, Koen van Zon, Liesbeth van de Grift and Paschalis Pechlivanis) as well as Martha Frederiks and Pim Huijnen for their critical feedback. Thanks to Cuno Balfoort who compiled the list of RNGOs. David Onnekink wishes to thank Jan Wolsheimer, Cornelis de Schipper, Berdine van den Toren, Evert and Janna van der Poll, Trees van Montfoort, Casper Havinga and Annemarthe Westerbeek for their valuable insights, and the RNGOs who made their annual reports available. Suzanne Ros wishes to express her gratitude towards Ruben Ros (Leiden University) for his helpful guidance with digital methods. Both authors thank the editors of this journal, in particular Tessa Lobbes, and the anonymous referees for their reports.

[2] https://www.rtvutrecht.nl/nieuws/3216040/14-klimaatactivisten-gearresteerd-na-urenlange-bezetting-pensioenkantoor-in-zeist (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[3] Aliene Boele, ‘Jonge christenen vinden dat kerken in actie moeten komen voor het klimaat’, Nederlands Dagblad, 3 December 2021.

[4] Allan Effa, ‘The Greening of Mission’, International Bulletin of Mission Research 32:4 (2008) 171-176. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/239693930803200402.

[5] David M. Konisky, ‘The Greening of Christianity? A Study of Environmental Attitudes Over Time’, Environmental Politics, 27:22 (2018) 267-291. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1416903.

[6] Published in 1967 as Lynn White, ‘The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis’, Science 155:3767 (1967) 1203-1207. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.155.3767.1203.

[7] E.g. Elspeth Whitney, ‘The Lynn White Thesis: Reception and Legacy’, Environmental Ethics 35:3 (2013) 313-331. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics201335328.

[8] On Protestantism as a coherent ‘movement’, see Jan A.B. Jongeneel, Protestantism as a worldwide renewal movement from 1945 until today. Panoramic Survey (Peter Lang 2022). DOI: https://doi.org/10.3726/b19753; and James Kennedy, Stad op een berg: de publieke rol van protestantse kerken (Boekcentrum 2010). On the complex nature of Dutch evangelicalism, see Pieter R. Boersma, ‘The Evangelical Movement in the Netherlands. New wine in new wineskins?’, in: Erik Sengers (ed.), The Dutch and their gods. Secularization and transformation of religion in the Netherlands since 1950 (Verloren 2005) 163-180.

[9] Until recently, overviews of Dutch Christianity had very little or nothing to say on the environment, see for instance Herman Selderhuis (ed.), Handboek Nederlandse Kerkgeschiedenis (Kok 2010); James R. Adair, Introducing Christianity (Routledge 2008) and Hugh McLeod (ed.), The Cambridge History of Christianity Vol. 9: World Christianities c. 1914-c.2000 (Cambridge University Press 2006). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521815000.

[10] E.g., Gregory. E. Hitzhusen, ‘Judeo-Christian theology and the environment: moving beyond scepticism to new sources for environmental education in the United States’, Environmental Education Research 13:1 (2007) 55-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620601122699; H. Paul Santmire and John B. Cobb, ‘The World of Nature according to the Protestant Tradition’, in: Roger S. Gottlieb, The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology (Oxford University Press 2006). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195178722.003.0005; Bernard Daley Zaleha and Andrew Szasz, ‘Why conservative Christians don’t believe in climate change’, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71:5 (2005) 19-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340215599789; Fred van Dyke, ‘Between heaven and earth—evangelical engagement in conservation’, Conservation Biology 19:6 (2005) 1693-1696. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00311.x.

[11] Michael S. Northcott, ‘Reformed Protestantism and the Origins of Modern Environmentalism’, Philosophia Reformata 83:1 (2018) 19-33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/23528230-08301003; Henk Jochemsen, ‘The Relationship between (Protestant) Christianity and the Environment is Ambivalent’, Philosophia Reformata 83:1 (2018) 34-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/23528230-08301001.

[12] Jan Luiten van Zanden and S. Wibo Verstegen also discovered the principle of waves of public environmental interest in the Netherlands, 1870-1930 and 1960-1980, in their Groene geschiedenis van Nederland (Utrecht 1993) 206.

[13] https://kerkenmilieu.nl/over-ons/geschiedenis/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[14] Drawing from the etymological and conceptual history of ‘the environment’ presented by Paul Warde, Libby Robin and Sverker Sörlin, we recognise this evolution to include science and politics related to climate. This expansion notably accelerated from the 1960s onwards, gaining momentum in the 1980s, as the concept of the environment emerged as an all-encompassing central concern for national agencies and became a frequent topic of discussion in academic conferences. Paul Warde, Libby Robin and Sverker Sörlin, The Environment: A History of the Idea (Johns Hopkins University Press 2018) 96-121.

[15] Marcel Broersma (ed.), ‘Nooit meer bladeren?: Digitale krantenarchieven als bron’, Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 14:2 (2012) 37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18146/tmg.135.

[16] The dataset obtained and used in this research was composed in September 2021; as a consequence, the data presented extends only to that date. Digibron currently provides access to more than 2.2 million articles, books and brochures from the period of about 1800 to the present. Utilising OCR (Optical Character Recognition) software, Delpher hosts millions of digitised texts from Dutch newspapers, books and magazines, enabling word-level searchability for its digitised publications. Optical character recognition (OCR) is a way in which computers extract pixels from a scanned book and convert them into text. Errors can arise when computers decipher unclear texts or handwritings, especially in texts produced before the 1850s. Recognising the challenges associated with OCR, we addressed potential errors through double manual correction, a solution also proposed by media historian Huub Wijfjes. See Huub Wijfjes, ‘Digital Humanities and Media History: A Challenge for Historical Newspaper Research’, Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 20:1 (2017) 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-7653.2017.277.

[17] Greta Franzini et al., On Close and Distant Reading in Digital Humanities: A Survey and Future Challenges. A State-of-the-Art (STAR) Report, 2015, 2; C. Annemieke Romein et al., ‘State of the Field: Digital History’, History 105:365 (2020) 291-312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-229X.12969.

[18] Self-evidently, this corpus does not cover the complete debate of Dutch Protestant reporting on climate change. Nevertheless, these digital methods enable the mapping of related articles from thorough databases of Dutch Protestant media and contribute to a more inclusive understanding of the debate.

[19] Hereinafter translated in this article as: church AND climate AND nature; climate change; climate AND environment; stewardship AND nature; greenhouse effect; environmental pollution; environmental awareness; sea level rise; climate goals; climate crisis. Utilising the ‘AND’ function, called ‘related searching’, allows for the retrieval of the relationship between two word(sets) and enables a more transparent and credible outcome. However, this method also assumes that there is a relationship between those words and needs careful consideration.

[20] This included non-Dutch historiography.

[21] To avoid ‘data massaging’, which means ‘altering wordlists and word values randomly’, we combined different methods in selecting the data, such as the aforementioned ‘related searching’ and setting this requirement of 120 results. Hieke Huistra and Bram Mellink, ‘Phrasing History: Selecting Sources in Digital Repositories’, Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 49:4 (2016) 225. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2016.1205964.

[22] The numbers of these graphs are set in proportion to the total number of articles in these newspapers of Digibron per year.

[23] Van Zanden and Verstegen, Groene geschiedenis, 196.

[24] Frank van Vree, De metamorfose van een dagblad: een journalistieke geschiedenis van de Volkskrant (Meulenhoff 1996).

[25] Van Vree, De metamorfose, 121-124.

[26] The visualisation of data from Delpher and Nexis Uni is presented in a combined figure, consisting of two separate plots. However, direct comparison of the numerical values between the plots is not feasible due to the utilisation of distinct datasets. Nevertheless, it is possible to make comparisons within each plot by analysing the data from de Volkskrant in conjunction with the data from the Nederlands Dagblad. The absence of online presence for the Nederlands Dagblad until 2007 resulted in the lack of data from 1995 to 2006, with the graphs beginning from 2007. The notable rise in de Volkskrant’s data in 1997 seems to be linked to articles discussing the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol by the UNFCCC, an international agreement aimed at controlling greenhouse gas emissions.

[27] The 2007 peak can be attributed to various factors, such as the widespread discussions surrounding Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth in 2006, numerous heat records in the Netherlands during 2007, the climate summit in Bali, and reports revealing that developing nations are experiencing the most severe effects of climate change damage. ‘“We moeten ons voorbereiden op extremen”: KNMI: 2007 wordt het warmste jaar ooit gemeten’, Nederlands Dagblad, 21 December 2007; ‘Arme landen dupe van warmer klimaat: Minister Koenders wil dat rijke landen helpen met extra geld’, Nederlands Dagblad, 28 November 2007; Peter Siebe, ‘Alle dingen verbeeldingskracht wat moeten we aan met Al Gore?’, Nederlands Dagblad, 1 September 2007.

[28] In 1971, Limits to Growth was presented at international conventions and discussed in the press. This explains the beginning of the increase in 1971.‘Ieder verantwoordelijk voor schoon milieu’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 29 May 1972; ‘Ook de Russen werken aan een oplossing van het vraagstuk, hoe de milieuverontreiniging teruggedrongen kan worden’, Nederlands Dagblad, 25 January 1971; ‘The “State of the Union”’, Nederlands Dagblad, 28 January 1971; ‘Leven op een eindige aarde’, Nederlands Dagblad, 23 March 1972; ‘Kringloop-Produktie’, Nederlands Dagblad, 24 March 1972; ‘Regering bereidt beslissing voor over aanpak milieuvervuiling’, Nederlands Dagblad, 25 March 1972; ‘Milieurecht, recht in wording’, Nederlands Dagblad, 15 April 1972; ‘G.W.G past doelstellingen aan mogelijkheden aan’, Nederlands Dagblad, 25 April 1972.

[29] Van Zanden and Verstegen, Groene geschiedenis, 10, 197; Geert Buelens, Wat we toen al wisten: De vergeten groene geschiedenis van 1972 (Querido Facto 2022).

[30] Hendrikus Berkhof, De mens onderweg (Boekencentrum 1960).

[31] Francis A. Schaeffer and Udo W. Middelman, Pollution and the Death of Man: The Christian View of Ecology (Crossway 1970).

[32] ‘Theologie kan bijdragen tot voortgang milieuzorg’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 5 July 1971.

[33] Hans Bouma, Adam, waar ben je? Mens contra natuur (Wytse Benedictus 1975) 34-35.

[34] ‘Nasleep van een ongeluk’, Nederlands Dagblad, 6 January 1971.

[35] E. Buijsman et al., Zure regen Een analyse van dertig jaar verzuringsproblematiek in Nederland (Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving 2010) 14.

[36] James Kennedy, ‘The Rise of a New Civil Society and the Decline of the Churches: The Dutch and the American Cases’, in: Traugott Jähnichen and Wilhelm Damberg (eds.), Neue soziale Bewegungen als Herausforderung sozialkirchlichen Handelns. Zur Neuformatierung der Zivilgesellschaft seit dem Ende der 1960er Jahre (Kohlhammer 2015) 31-48.

[37] Tini Brugge, Als de Schepping zucht (Kok 1988); A timeline constructed by Kees Tinga, based on the archive of the Council of Churches in Emmen, is on: https://kerkenmilieu.nl/over-ons/geschiedenis/.

[38] https://kerkenmilieu.nl/over-ons/geschiedenis/.

[39] Evert van der Poll and Janna Stapert, Als het water bitter is: evangelisch denken en de milieucrisis (Merweboek 1988). The title was inspired by Exodus 15:23.

[40] ‘Wie Betaalt?’, Nederlands Dagblad, 11 January 1989.

[41] ‘Wie Betaalt?’, Nederlands Dagblad, 11 January 1989; ‘VVD wil 5 miljard extra aan zorg voor milieu besteden’, Nederlands Dagblad, 10 March 1989.

[42] ‘Milieubeleid omvat meer dan tot op heden gebruikelijk was’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 19 September 1989; ‘Nationaal Milieubeleidsplan is uitgebalanceerd compromis’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 19 March 1989; ‘Nationaal milieubeleidsplan’, De Banier, 2 June 1989.

[43] ‘VN moeten aantasting atmosfeer tegengaan’, Nederlands Dagblad, 14 March 1989.

[44] ‘VVD wil 5 miljard extra aan zorg voor milieu besteden’, Nederlands Dagblad, 10 March 1989.

[45] Van Zanden and Verstegen, Groene geschiedenis, 10.

[46] Wim van der Zee, ‘Kerkelijk Nederland in Conciliair Proces’, Christendemocratische verkenningen 5 (1989) 185-194.

[47] ‘Milieu krijgt nu volop aandacht in de kerk’, De kleine aarde 65 (1988) 10.

[48] This was also the observation of Henk Jochemsen: in Gerald Bruins, ‘Omgang met schepping leeft niet bij christenen‘, Nederlands Dagblad, 22 May 2014.

[49] Kerknieuws, 21 April 1989.

[50] ‘Kerkelijke inhaalmanoeuvre’, in: Het Utrechts Archief (hereafter HUA) 1368 Raad van Kerken 1982-2000, inventaris 1640, (Depot Emmen).

[51] HUA 1368 Raad van Kerken 1982-2000, inventaris 1640, (Depot Emmen).

[52] This is the gist of the lectures by Klarissa Nienhuys of the Stichting Natuur en Milieu and Bishop Ernst, in: HUA 1368, 1641.

[53] ‘Milieu krijgt nu volop aandacht in de kerk’, De kleine aarde 65 (1988) 10.

[54] ‘Christelijke ethiek nodig tegen weerbarstige werkelijkheid: Milieudefensie vindt kerkvrienden’, 5 October 1991, HUA 1368, 1642; Jaap de Berg, ‘Weg met grote woorden, small is beautiful’, Trouw, 28 December 1991.

[55] HUA 1368-1637 papers related to Zirrcon. Cf. Marthinus L. Daneel, African Earthkeepers: Wholistic Interfaith Mission (UNISA Press 1998).

[56] At Ipenburg, ‘Afrikaanse spiritualiteit en het behouden van de schepping. Het ZIRRCON boomplantproject in Zimbabwe. ‘Responding to the Call of the Earthkeeping Spirit’, in: HUA 1368-1637 Zirrcon.

[57] ‘Was de wereld maar complex’, Nederlands Dagblad, 14 July 2009.

[58] ‘“Groene” Kerk krijgt certificaat “tienden energie besparen”’, Nederlands Dagblad, 10 December 2009; ‘Waartoe op aarde bezweken herontdek de Kerk met “groene diaken”’, Nederlands Dagblad, 17 October 2009; ‘Geef klimaathulp naast armoedebestrijding. Oproep Micha campagne aan Europese Raad’, Nederlands Dagblad, 28 October 2009; ‘Landbouw bliksem in Halle luiden kerkklokken voor het klimaat kerkklokken klinken over hele wereld’, Nederlands Dagblad, 12 December 2009.

[59] ‘Christenen op weg naar de top van Kopenhagen’, Nederlands Dagblad, 17 October 2009.

[60] Theo Koelé, ‘Hulpverlener draagt vaak een pak. Ontwikkelingsorganisaties weren zich op jubileumdag tegen aanvallen op hun “linkse hobby”’, De Volkskrant, 28 September 2009.

[61] Kerkredactie, ‘Organisaties starten actie voor klimaat’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 22 September 2009.

[62] Arjan van de Waerdt and Jacques Rozendaal, ‘Durf stap terug te doen in welvaart’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 18 December 2009.

[63] https://groenekerken.nl/meer-informatie/; https://groenemoskeeen.nl/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[64] https://kerkenmilieu.nl/over-ons/geschiedenis/; https://www.raadvankerken.nl/thema/duurzaamheid/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[65] We owe the latter observation to Berdine van den Toren. According to Trees van Montfoort renewed interest in the environment became visible in the early-2010s. Trees van Montfoort, Groene Theologie (Skandalon 2019) 15.

[66] For instance Julie Hearn, ‘The “invisible” NGO: US evangelical missions in Kenya’, Journal of Religion in Africa 32:1 (2002) 32-60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700660260048465; Julia Berger ‘Religious nongovernmental organizations: an exploratory analysis’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 14 (2003) 15-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022988804887.

[67] Carolyn Peach Brown et al., _‘_An investigation of perception of climate change risk, environmental values and development programming in a faith-based international development organization’, in: Robin Globus Veldman et al. (eds.), How the World’s Religions are Responding to Climate Change (Routledge 2014) 261.

[68] Although these include several companies, churches and educational institutions, the vast majority can be classified as RNGOs. All these organisations are listed on the websites of the NZR, Missie Nederland and Prisma: https://zendingsraad.nl/; https://www.missienederland.nl/; https://www.prismaweb.org/nl/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[69] Based on the financial reports of these organisations, see below.

[70] On this topic, see Jeremy Kidwell, ‘Mapping the field of religious environmental politics’, International Affairs 96:2 (2020) 343-363. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz255.

[71] GZB annual report 2020, 61.

[72] 3xM, Annual Report 2020, https://3xm.nl/jaarverslag-2020/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[73] Peach Brown et al., _‘_An investigation’.

[74] For instance, the annual report Publieksmonitor Klimaat en Energie of the Dutch Ministry of Economics and Climate does not mention religious persuasion. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, in association with the Protestant Theological University, Tussen duurzaam denken en duurzaam doen. Houding, gedrag en veranderbereidheid van religieuze en niet-religieuze Nederlanders als het gaat om klimaat (Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau and the Protestant Theological University, 2024).

[75] Micha Monitor 2014, 39.

[76] Gerald Bruins, ‘Omgang met schepping leeft niet bij christenen‘, Nederlands Dagblad, 22 May 2014.

[77] Delen laat zich niet gemakkelijk vermenigvuldigen: Micha Monitor 2012, https://www.michanederland.nl/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Micha-Monitor-2012-styled-def.pdf (2012) 11; Rechtvaardigheid: waarom doen we dat (niet)? Resultaten Micha monitor 2014, https://www.michanederland.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/2e-Micha-Monitor-2014.pdf, 11. Last accessed 4 April 2024. On Christianity and animal rights, see for instance Andrew Linzey, Creatures of the same God. Explorations in animal theology (Lantern Books 2009).

[78] Micha Monitor 2014, 24.

[79] Micha Monitor 2012, 26.

[80] Van der Ziel, Groene activiteiten, 11.

[81] Peach Brown et al., ‘An investigation’, 261-262.

[82] Mary Evelyn Tucker, ‘Religion and ecology: survey of the field’, in: Roger S. Gottlieb (ed.), The Oxford handbook of religion and ecology (Oxford University Press 2018) 9.

[83] Jay L. Michaels et al., ‘Beyond stewardship and dominion? Towards a social psychological explanation of the relationship between religious attitudes and environmental concern’, Environmental Politics 30:4 (2020) 622-643. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1787777.

[84] Micha Monitor 2012, 25, 27.

[85] Micha Monitor 2014, 44.

[86] Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau and Protestantse Theologische Universiteit, Tussen duurzaam denken en duurzaam doen.

[87] Cors Visser, ‘Onderzoek: christenen en duurzaamheid. Niet de kerk maar geloof inspireert tot groen doen’, CV Koers 27 April 2010, 16-17.

[88] https://kerkenmilieu.nl/over-ons/geschiedenis/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[89] Visser, ‘Onderzoek: christenen en duurzaamheid’, 16-17.

[90] Maarten Keulemans, ‘De klimaatverandering is nu echt begonnen’, de Volkskrant, 20 December 2019.

[91] https://www.christianclimateaction.nl/about/ (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[92] https://www.hetgroenenormaal.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Het-Groene-Normaal_manifest_online.pdf (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[93] https://www.justiceconference.nl/partners-justice-conference. (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[94] E.g. Nienke Pruiksma (ed.), De schepping in het midden: klimaatcrisis als theologische uitdaging (Nederlandse Zendingsraad 2020).

[95] https://www.christianclimateaction.nl/acties/brief-aan-scriba-en-moderamen-pkn/. The letter referred to actions culminating in the joint declaration of Pope Francis, Anglican Archbishop Welby and Orthodox patriarch Bartholomeus on 9 September 2021 in the run-up to the World Climate Summit in Glasgow. (last accessed 4 April 2024).

[96] Encyclical, Laudato si, 24 May 2015, paragraph 25.

[97] Patriarch Bartholomew, Pope Francis, Archbishop Justin, A joint message for the protection of creation, 1 September 2021.

[98] E.g. Gerco Verdouw, ‘“Het kabinet maakt er een zootje van”’, Reformatorisch Dagblad, 25 June 2021; ‘Oneerlijke stikstofmetingen’, De Banier, 1 November 2019.

[99] Gerard ter Horst and Hilbert Meijer, ‘Politieke statements in de kerk’, Nederlands Dagblad, 2 March 2019.

[100] Micha measured the extent to which churches paid attention to sustainability, whereas Van der Ziel researched in which form they did so. Tjirk van der Ziel, Groene activiteiten: Een impuls voor kerken en samenleving (Christelijke Hogeschool Ede 2021) 10.

[101] Van der Ziel, Groene activiteiten, 4.

[102] Highlights Jongerenonderzoek naar de toekomst, de kerk, het geloof (November 2021). https://www.missienederland.nl/l/library/download/urn:uuid:5ff2342f-9381-4df6-9381-1a65fdc8bf81/highlights+jongerenonderzoek+toekomst%2C+-kerk+en+geloof.pdf?format=save_to_disk. (last accessed 4 April 2024).